Coronavirus: UK borrowing to see 'colossal increase' to fight virus

- Published

- comments

The UK's budget deficit is set to see "an absolutely colossal increase to a level not seen in peacetime", the director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies has said.

The economic impact of coronavirus was likely to push the deficit to as high as £260bn, Paul Johnson told the BBC.

He was speaking after latest figures showed that the deficit hit £48.7bn in the 2019-20 financial year.

But Mr Johnson said those figures were "the numbers before the storm".

And, separately, one of the Bank of England's top policymakers has warned that the UK faces its worst economic shock in several hundred years.

Jan Vlieghe, a member of the BoE's interest-rate setting committee, said that "early indicators" suggest the UK was "experiencing an economic contraction that is faster and deeper than anything we have seen in the past century, or possibly several centuries".

He did, though, say there was "in principle" a good chance that the UK would return to its "pre-virus trajectory once the pandemic is over".

The UK's deficit last year - the gap between the government's income and its expenditure - was £9.3bn higher than in the 2018-19 financial year and equivalent to 2.2% of GDP.

The Office for National Statistics, which released those figures, said they did not capture the big spending announced by the government to cope with the virus.

"The coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic is expected to have a significant impact on the UK public sector finances," it added.

"These effects will arise from both the introduction of public health measures and from new government policies to support businesses and individuals."

Tax rises

The ONS said the full effects of coronavirus on the public finances would become clearer in the coming months.

Mr Johnson told the BBC's Today programme that there was still "a huge amount of uncertainty" surrounding the economic impact of the virus.

However, the government had announced tax cuts and spending increases worth £100bn, so the effect was "likely to dwarf the record that we saw during the financial crisis".

Mr Johnson said the economy was unlikely to recover quickly afterwards and would remain "smaller than it otherwise would have been". He added that tax rises and a growing deficit were the likely outcome.

"I would be astonished if in a couple of years the economy was back where it would have been if it [the virus] had never happened," he said.

Meanwhile, a closely watched survey of UK businesses has indicated that the economic impact has been even worse than feared.

The IHS Markit/CIPS flash UK composite purchasing managers' index (PMI), which measures activity in the services and manufacturing sectors, fell to a new record low of 12.9 in April, down from 36 in March.

Any reading below 50 indicates contraction. Economists polled by Reuters had expected a figure of 31.4.

"The dire survey readings will inevitably raise questions about the cost of the lockdown and how long current containment measures will last," said Chris Williamson, chief business economist at IHS Markit, adding that the figures pointed to a quarter-on-quarter economic contraction of at least 7%.

Raising money

In another development, the Treasury has announced that it is speeding up its plans to raise money in order to cover the cost of its coronavirus measures.

It will now be issuing £180bn worth of government bonds, known as gilts, in the May-to-July period, more than originally intended in those months.

We already knew the government was likely to have to borrow huge sums of money to support the economy. But now it's not a "scenario" from the Office of Budget Responsibility, but concrete reality.

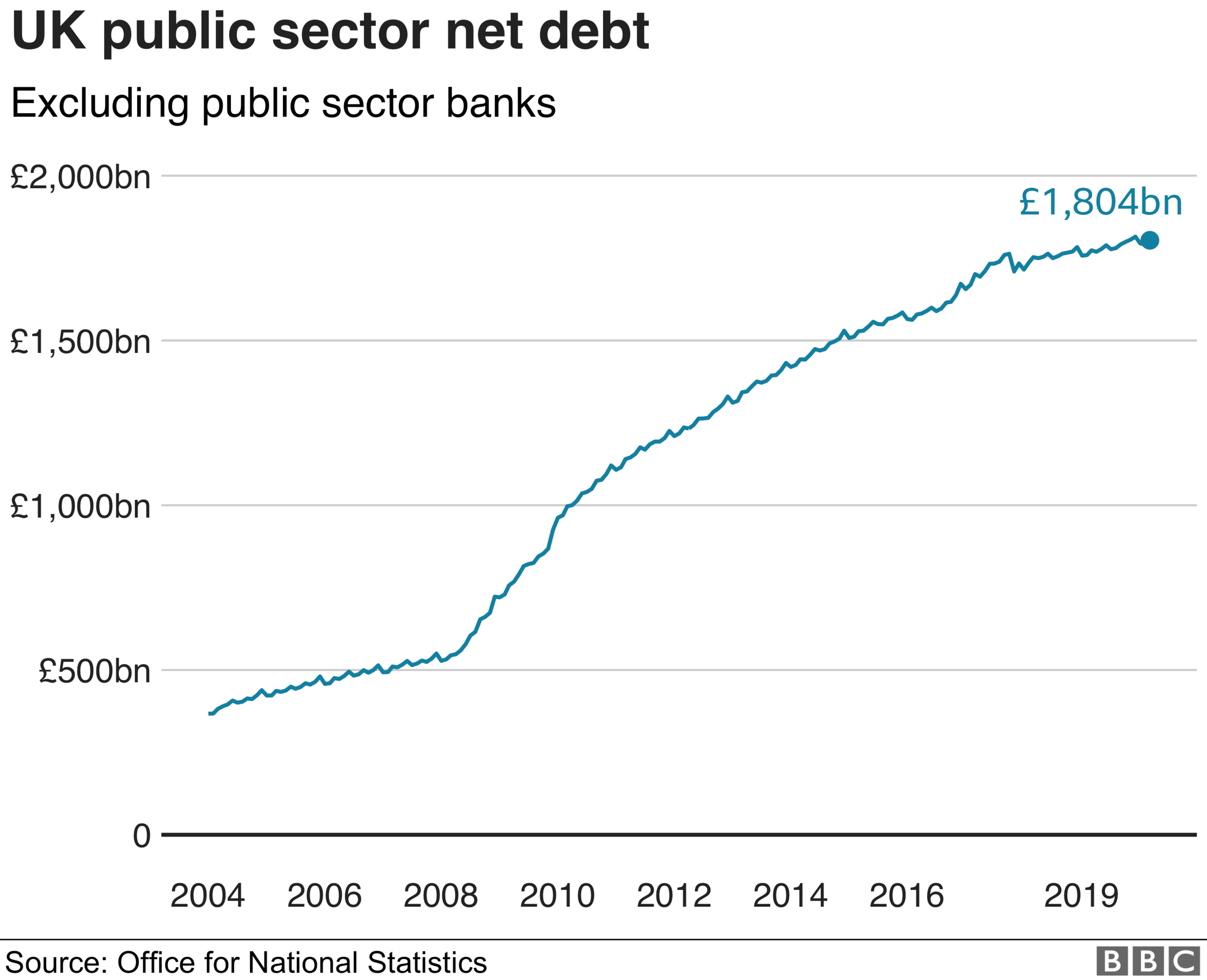

This morning, the Debt Management Office, the arm of the Treasury that borrows on international money markets on behalf of the government, announced how much the government is actually planning to borrow. That's £45bn in April alone and a further £180bn from the start of May to the end of July - a total of £225bn in just four months.

One reason is the huge cost of programmes such as furloughing, now expected to cost well north of £50bn. The other reason is that the government's revenues - the tax it collects through income tax, VAT and national insurance - are collapsing. If you shut down much of the economy, you also turn off the tap on much of the government's tax income.

The OBR's scenario was that the government might need to borrow £382bn for the year - about seven times what was expected pre-Covid. That depends, though, on the shutdown being lifted sooner rather than later.

The Resolution Foundation estimates that if the shutdown continues for six months, borrowing will be even higher for the year - a truly mind-boggling £500bn. That's about a quarter of the size of the entire economy.

"The temporary and immediate nature of the unprecedented support announced for people and businesses means the government expects that a significantly higher proportion of total gilt sales in 2020-21 will take place in the first four months of the financial year, in order to meet the immediate financing needs resulting from Covid-19," the Treasury said.

"This higher volume of issuance is not expected to be required across the remainder of the financial year."

- Published22 April 2020

- Published21 April 2020