UK-US trade talks will not be an easy ride

- Published

Navigating relationships via video calls has become a defining feature of the lockdown - and policymakers are no exception.

As International Trade Secretary Liz Truss and the US trade representative Robert Lighthizer kick off talks remotely, they're hoping that a long distance courtship won't be an obstacle to deeper ties - a deal which boosts output and jobs by cutting the charges and restrictions on trade.

The "special relationship" is already a lucrative one. More than £220bn worth of goods and services are traded between the two nations, their companies responsible for millions of jobs on the other's home turf.

The UK is hoping to capitalise on its new-found ability to strike free-trade deals with more opportunities for exporters of cars, ceramics and whisky, for example.

However, this won't be an easy ride into the sunset.

Both sides are desperate for speed, to show at least some easy wins, perhaps in areas such as manufactured goods or financial services.

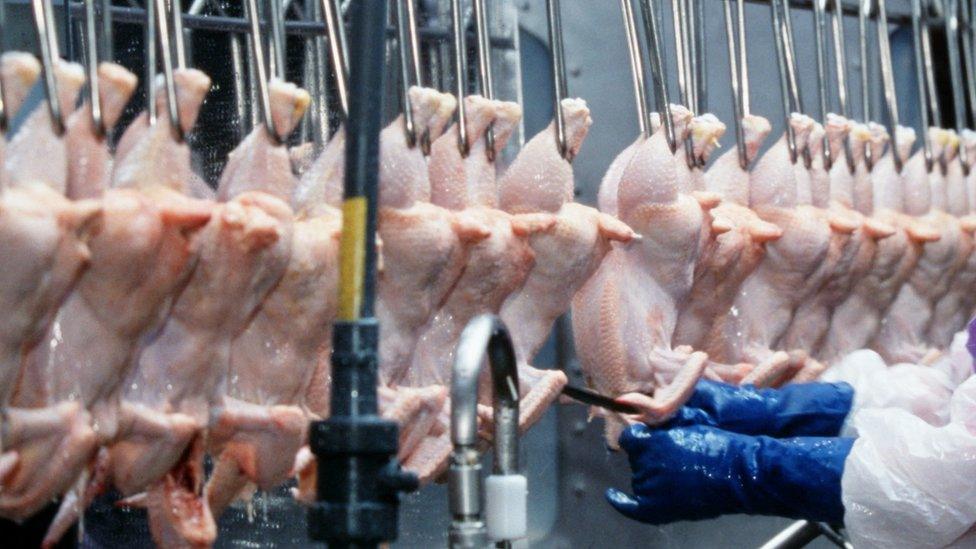

But there are sticking points. The US wants more access for its farmers to British markets, cue talk of chlorinated chicken and hormone treated beef.

President Trump is unlikely to back down on this as he tries to woo voters ahead of an election in country where one in six workers have filed for unemployment benefits in recent weeks.

Food is likely to be one of the areas of biggest contention

And more access is likely to mean the UK having to relax standards and regulations - that, along with areas such as pharmaceutical prices, will meet with strenuous opposition from this side of the water.

Even if these hurdles are overcome, the gains may be modest. The Department for International Trade's own analysis suggests that Britain's economy would be just 0.16% - or £3.4bn - bigger in 15 years - if all tariffs with the US are eliminated. And that scenario goes beyond the UK's objectives; in reality, the boost could be even smaller.

Brexit talks

Crucially, these are not the only trade talks troubling Whitehall's IT capability; those with Brussels over the future relationship with the EU stagger on.

Despite British hopes of a deal by the end of the year, and a refusal to extend the transition period, the Irish Foreign Minister Simon Coveney has warned that the talks may reach crisis point unless progress is made soon.

The stakes there are even higher; studies suggest the gain from a US deal would only go a small way to compensate for the hit to UK growth from even a Free Trade Agreement with Europe compared to what may have resulted from continued membership of the EU. An even looser relationship with the EU with more restrictions would widen that gap.

The government is keen to use its new-found freedom on the trade circuit to show it can create new opportunities and prosperity.

But failure to deliver, or to carefully manage a delay, could come with a high price tag at this delicate point for the economy

- Published4 May 2020

- Published26 January 2024

- Published21 February 2020