Finding the 'invisible' millions who are not on maps

- Published

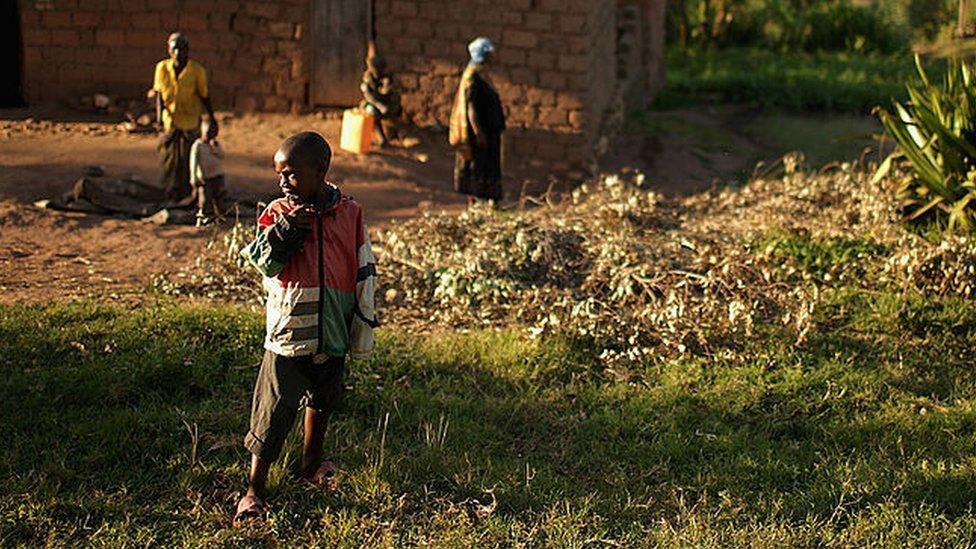

There are often no maps of rural areas of Rwanda

"There are about two billion people in the world who don't appear on a proper map," says Ivan Gayton from the charity Humanitarian OpenStreetMap.

"It's shameful that we - as cartographers of the world - don't take enough interest to even know where they are. People are living and dying without appearing on any database."

Known as the "Wikipedia for maps", anyone can download OpenStreetMap and edit it too.

"It's an amazing situation where anyone could wreck it, anyone can add to it, but what we've ended up with is a map that is the most up-to-date in some places."

According to Mr Gayton, it is the most complete and accurate map for many parts of the world, especially in rural Africa, where underinvestment means, outside of cities, there are often blank pages where millions live.

Ivan Gayton believes better data will solve critical healthcare issues

As we sit in Rwanda, Mr Gayton gestures into the distance: "It's not very far from here, over in the Democratic Republic of Congo just across the border, where the information all but stops. It's not like people don't live there, they just aren't recorded."

So why does it matter?

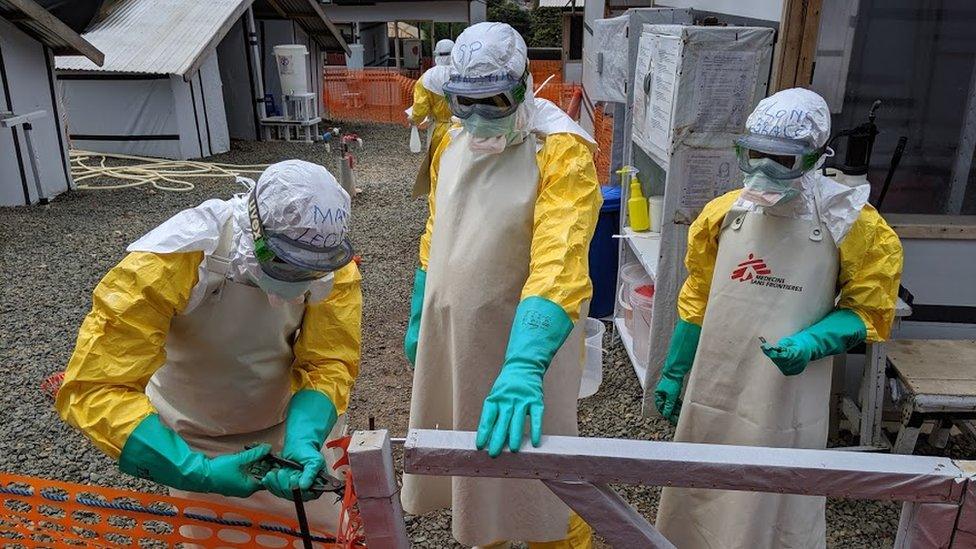

Mr Gayton says it can be a matter of life and death. "If you take an outbreak of disease like Ebola or the new coronavirus, contact tracing is how you stop epidemics. It's not the treatment, it's the public health and map data that makes it possible."

He worked on mapping efforts during the West Africa Ebola outbreak of 2014-15, and found a lack of data caused critical problems in locating disease hotspots.

"If you come into a health facility anywhere in the world with a communicable disease, they'll ask you where you're from. In the low-income world you don't always have a system for describing that location."

Health workers at an Ebola treatment facility in Sierra Leone

This is something that Liz Hughes, chief executive of Map Action, is passionate about too. Her organisation helps provide maps for aid agencies and governments, using both technology and volunteers.

She cites examples such as flooding, where up-to-date maps are needed urgently. "We can work out where the most critical need is, and then aid can be better targeted in a natural disaster or epidemic situation."

The big technology firms have invested huge amounts into their mapping efforts, but Ivan Gayton says there is a clear gulf in terms of priority.

"There isn't much commercial incentive for Google to identify the nearest Starbucks in the Democratic Republic of Congo," he says.

Maps are the building blocks of economic development. Without accurate maps it's not just navigating from A to B that can be difficult - the essential tasks of proper planning for housing and infrastructure can be impossible.

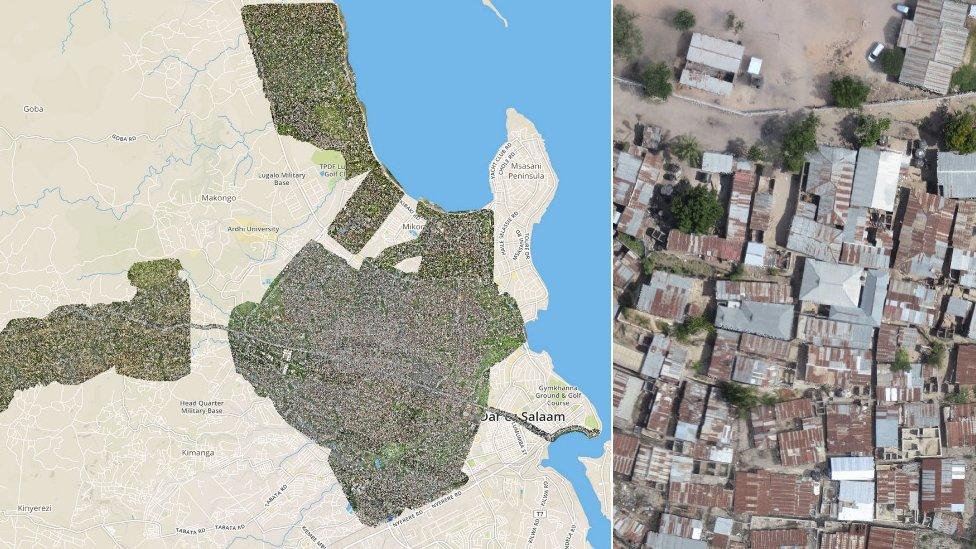

Dar es Salaam is rapidly urbanising

The World Bank's Edward Anderson has worked on mapping efforts for the last decade, first in the Pacific, and now in Africa. He says that traditionally, maps were done at a national level, and it could take years between a survey and the production and application of the map.

"Cities are especially a problem, because we are seeing very rapid urbanisation, and the fastest rate of unplanned urbanisation in history. Around 80% of the growth in urban areas is unplanned, and 70% of new residents in cities are entering slums.

"Quite often the maps city planners have to use are 10 years old."

This means, he says, that authorities are always playing catch-up.

One of those capitalising on the need for mapping is Tanzanian entrepreneur Freddie Mbuya. Mining companies pay him to map their land using drones. This kind of detailed mapping needs to be done frequently, often in areas that are hard to reach.

Land is key to fighting poverty but we can't do this if we don't know where the land is, says Freddie Mbuya

He says global technology companies don't have the incentive to map to a local scale in rural Africa, which would be time-consuming and costly.

"Google and Apple maps do not differentiate between a good road and a bad road - but that's so important," he says.

Mr Mbuya adds that land titling is also critical for development.

"Land is the key to fighting poverty. But how can we do this if we don't know where our land is? If the land isn't titled we cannot leverage the value of our land. Most of my family land has been lost or is not being developed - we need land to be surveyed and formalised…. so we can go to a bank and get a loan with a piece of paper saying I own this land."

Scottish geographer Paul Georgie is the founder of mapping company Geo Geo.

He says in today's digital society, not being on a map is akin to being invisible. "Even just having your house or your hut or your village on a map, with the associated roads, is vital for the government to help with planning."

He worked on a project in Tanzania setting up energy grids in remote communities.

Liz Hughes says maps are often needed instantly after disasters

"We downloaded rough satellite images and took them into villages. Maps speak a universal language and people were able to label the pictures. Formalising this, mapping it and making it tangible gives people a larger voice around the world."

Labelling and filling in the blanks is also being done by volunteers around the world.

Liz Hughes from Map Action explains: "In places like Sierra Leone, while we were working on the Ebola response, we couldn't even find maps to show where the roads were, and out of that was born the Missing Maps."

Once a month in cities like London and New York, enthusiasts get together to work on these maps, using open data and volunteer contributions to help fill in the blanks online.

A volunteer mapper in Dar es Salaam

Map Action also works to train volunteers on location.

"We train people in knowing what might be needed on the ground. An example would be Ebola in Sierra Leone. We worked with the UK's health adviser to work out where would be best to put water points for handwashing," says Ms Hughes.

Volunteers are used in community projects across Africa, including in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania's rapidly urbanising commercial hub.

Here student volunteers for a project called Ramani Huria map using simple apps on smartphones in the many unplanned areas where drainage and flooding are frequent and deadly issues. These help local authorities trace where cholera outbreaks may occur in clusters.

The World Bank's Edward Anderson says that community-led mapping gives valuable immediacy to the information.

"We need to update the data on a yearly or quarterly basis, in a bottom-up way. Nearly every urban adult has access to a smartphone now. So we can use this community-collected data to really update our knowledge of the informal areas.

"They're unplanned, but clearly people know their own names for streets and where the water points and communal toilets are, they're just not on any map."

Mappers creating up-to-date information

But Ivan Gayton acknowledges that the public health argument for comprehensive mapping doesn't convince everyone. It will, he says, be an economic incentive that wins over cynics.

"The most compelling use case for the average person is to get a pizza or order a cab. My belief is that as the technology makes it possible for people not to have to spend half a day working out where their driver is, they will do it. People want to do business."