Coronavirus: No guarantee of quick economic bounceback, warns Sunak

- Published

It is "not obvious there will be an immediate bounceback" for the UK economy, once lockdown restrictions are eased, the chancellor has warned.

Rishi Sunak said he hoped for a swift recovery, but it could take time for the UK economy to get back to normal.

"It takes time for people to get back to the habits that they had, there are still restrictions in place," he said.

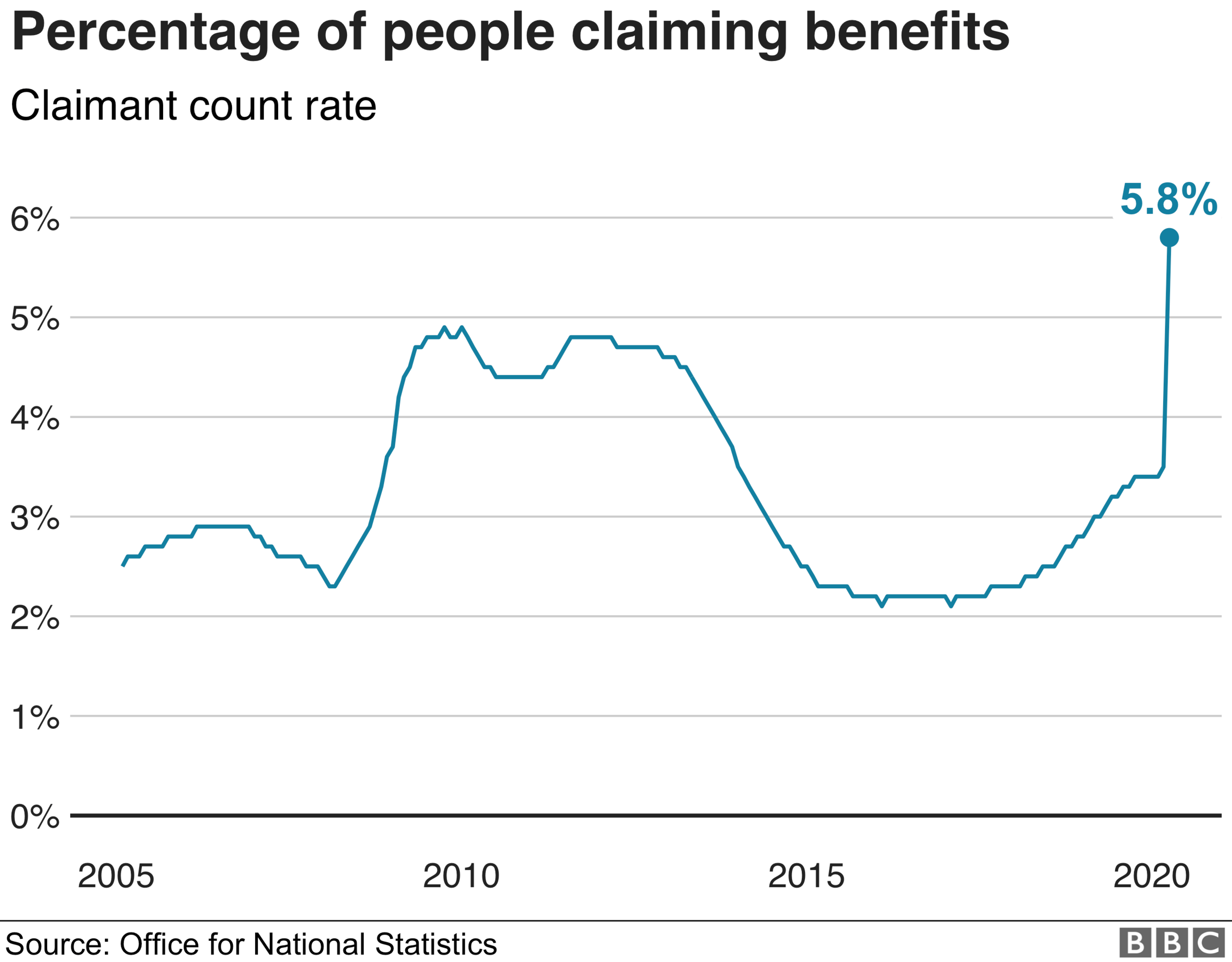

His warning came as figures showed the number of people claiming unemployment benefit soared to 2.1 million in April.

The jump of 856,500 claims in April reflected the impact of the first full month of lockdown, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) said.

The government has made some changes to who can claim work-related benefits during the pandemic, but this figure is one of a series that show the stress Covid-19 is putting on the jobs market.

'Jury's out'

Speaking to the Lords Economic Affairs Committee, Mr Sunak said figures from around the world where countries were progressively easing and lifting restrictions, suggested a full recovery could take time.

He said the "question that occupies" his mind was "what degree of long-term scarring is there on the economy" and that once restrictions begin to be lifted there will be the case of "what do we return to" and on that the "jury's out".

But he admitted he felt "all economic forecasters and economists would agree the longer the recession is, it is likely the degree of that scarring will be greater".

He said that even if the government can reopen retail in England as planned on the 1 June, there will still be restrictions on how people can shop.

This will have an impact on how much they spend, and on how many people go out, Mr Sunak said.

"I think in all cases it will take a little bit of time for things to get back to normal, even once we've reopened currently closed sectors," Mr Sunak added.

When quizzed on unemployment by the committee, Mr Sunak said he did not have a precise estimate for what the numbers would be at the end of the year.

However, he said: "Obviously, the impact [of the coronavirus pandemic] will be severe."

Before the lockdown began, employment had hit a record high.

In another indication of the bleak employment landscape, the number of job vacancies fell by nearly a quarter to 637,000 in the three months to April.

'The week after I left the company, Covid hit'

Meanwhile, claims for universal credit - the benefit for working-age people in the UK - hit a record monthly level in the early weeks of lockdown.

Unemployed HR worker Jon Ellis-Fleming, of Keighley in West Yorkshire, had been with an outsourcing company for more than four years when he was made redundant.

He left the firm on 8 March, hoping to spend some time at home with his partner Julia Paterson and their eight-month-old daughter Daisy while looking for a new job.

"The week after I officially left the company, Covid hit," he told the BBC. That meant that several promising job offers just evaporated as firms put their recruitment plans on hold.

Jon applied for universal credit and jobseeker's allowance. He is due to receive his first payment of £600 later this month, while his partner receives £650 a month on maternity leave.

That leaves them with less than half of their former income - and with another mouth to feed as well.

"I've not been out of work in 10 years," he said. "I've never had any intention of being out of work that long.

"I can't help but wonder, if I'd been with the company two weeks longer, would furloughing have been an option?"

The unemployment rate was estimated at 3.9%, slightly down on the previous quarter, the ONS said., external

The jobless figures only cover the first week of the lockdown and they are expected to worsen sharply in the coming months.

Jagjit Chadha, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research, told the BBC: "We can reasonably expect unemployment to rise very quickly to something over 10% - something we haven't seen since the early 1990s."

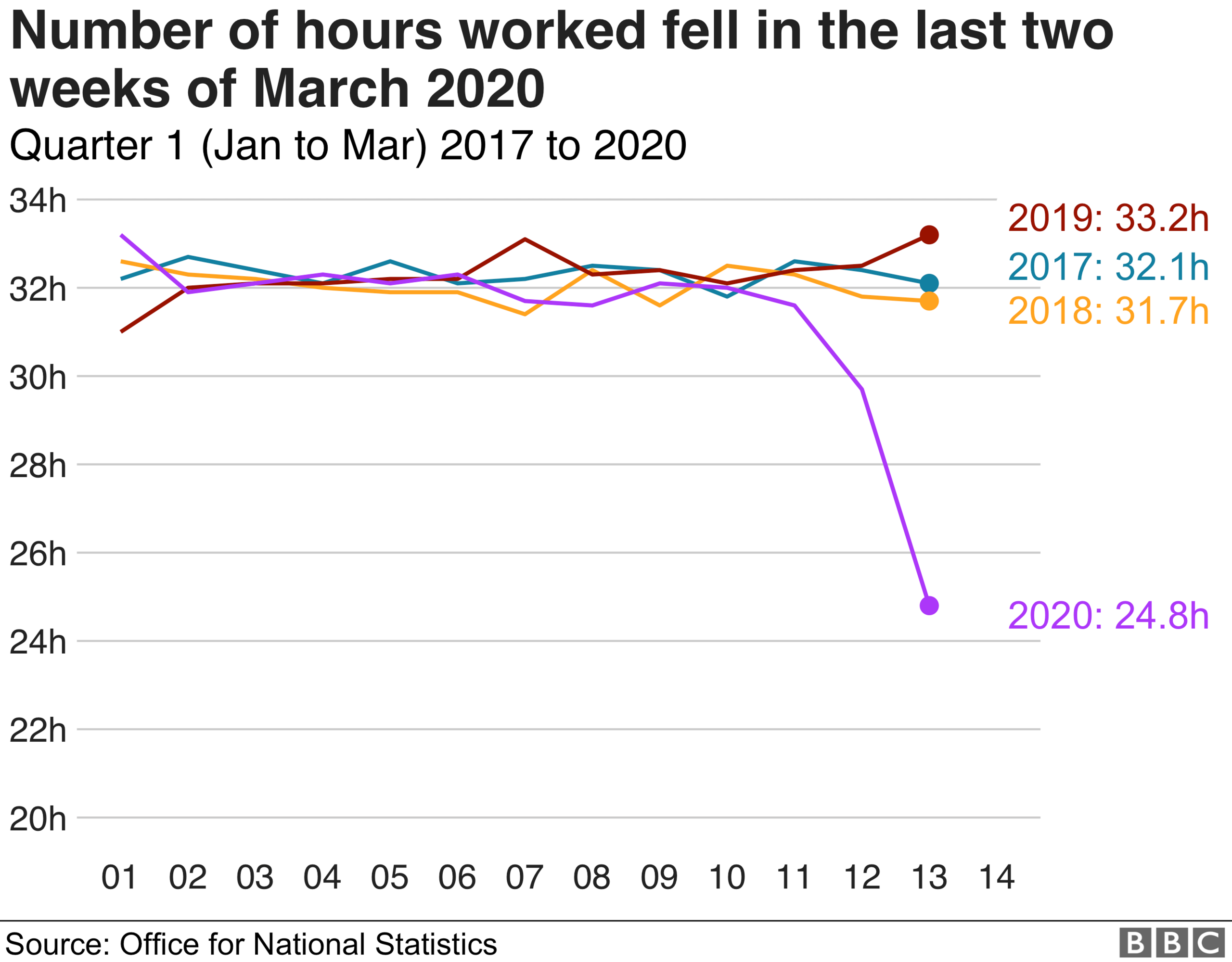

Estimates based on returns for individual weeks suggest that the fall in the unemployment rate was mostly caused by the decrease in hours in the last week of March, with a much smaller decrease in the previous week, the ONS said.

In the final week of March, the total number of hours worked was about 25% fewer than in other weeks within the quarter.

The government's jobs schemes succeeded in keeping the headline jobs numbers high, and jobless data still quite low up until the end of March.

But there is evidence of the pandemic crisis impact starting to hit in the latest ONS jobs market release.

The number of job vacancies from February to April tumbled by 170,000 to 637,000 - a record quarterly fall. The claimant count jumped in April, while the average hours worked in a week fell sharply at the end of March.

So the signs of a significant downturn in the normal jobs market are there, but as is the impact of the extraordinary government support package. Unemployment would have shot through the roof without this support.

However, these numbers will get worse with next month's figures. The vacancy drop shows there are fewer jobs out there for those who do lose work. And there are real concerns as to what happens when the support starts to be phased away in August.

RISK AT WORK: How exposed is your job?

THE R NUMBER: What it means and why it matters

LOOK-UP TOOL: How many cases in your area?

RECOVERY: How long does it take to get better?

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

Are you claiming unemployment benefit? Share your experiences by emailing haveyoursay@bbc.co.uk, external.

Please include a contact number if you are willing to speak to a BBC journalist.

WhatsApp: +44 7756 165803

Tweet: @BBC_HaveYourSay, external

Please read our terms & conditions and privacy policy

- Published26 March

- Published19 May 2020

- Published19 May 2020

- Published19 May 2020

- Published14 May 2020

- Published13 May 2020