How bad are China's economic woes?

- Published

Official unemployment numbers are close to historic highs - and the real figure is probably even higher

While economists say China's economic data can't always be trusted, they now have a new dilemma - there is no data.

On Friday, China said it wouldn't be setting a target for economic growth for this year.

That's unprecedented - the Chinese government hasn't done this since it began publishing such goals in 1990.

Abandoning the growth target is an acknowledgement of just how difficult a recovery in China will be in a post pandemic era.

And while recent figures have shown that China is on the way out of its slowdown: it's an uneven recovery.

First, the good news.

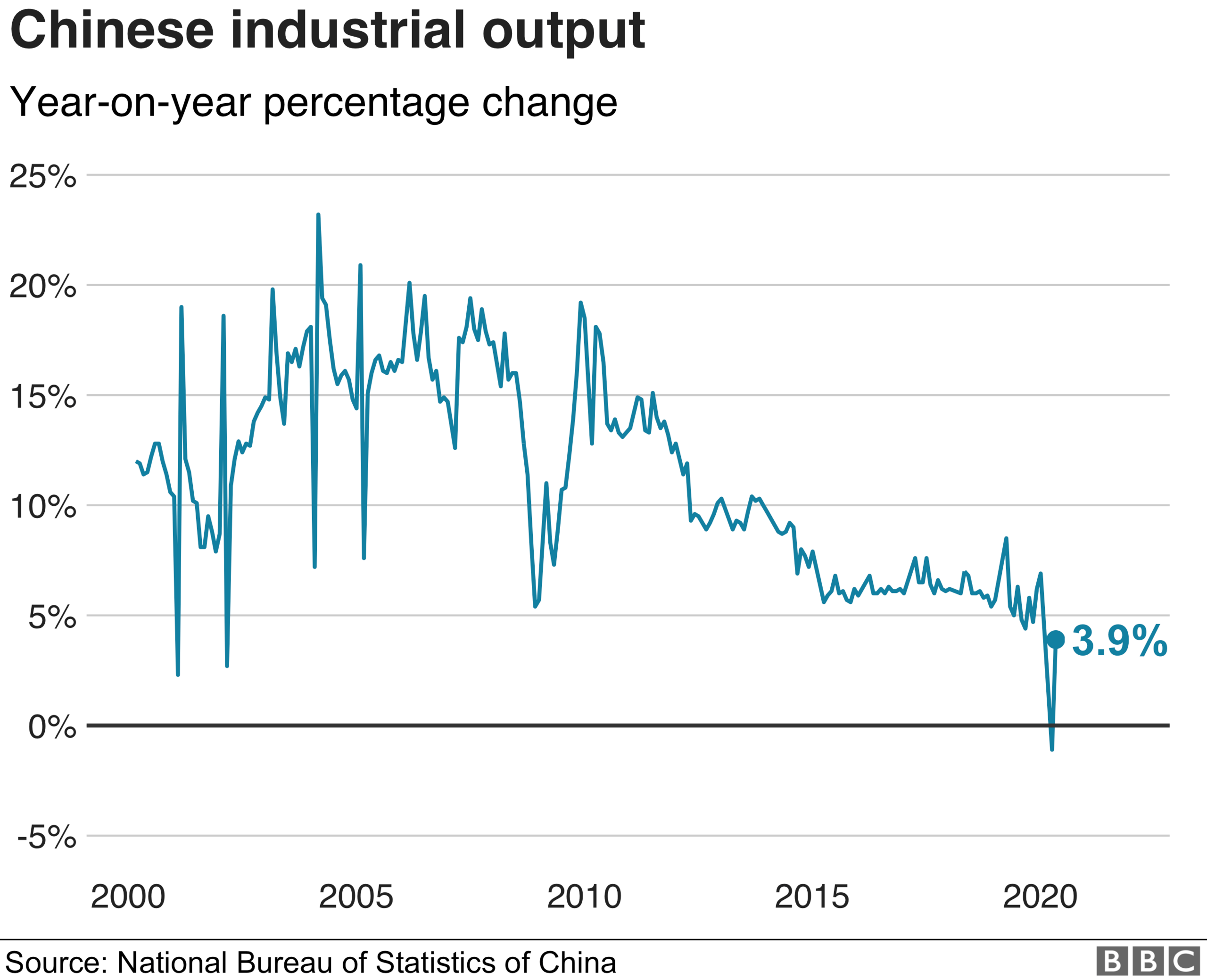

For the first time since the pandemic hit China - factories are making goods again.

Industrial output in April grew by a better-than-expected 3.9% - a marked difference from the collapse of 13.5% in the first two months of this year as massive lockdowns were imposed.

There's also a swathe of other data that has been surprisingly strong - pointing to what economists like to call a V-shaped recovery - a sharp, drastic initial fall - followed by a quick rebound in economic activity.

Coal consumption by six major power generators surged back to historical norms after May's "Golden week" holidays, according to investment bank JP Morgan. It currently stands 1.5% above the historical average, suggesting that power demand has returned to normal.

And the pollution-free Chinese skies that we saw in the aftermath of the lockdowns there - well, they've disappeared as economic activity has picked up.

China's air pollution levels recently surpassed concentrations over the same period last year for the first time since the coronavirus crisis began, driven by industrial emissions.

All of this shows that China is slowly getting back to business.

But it's not business as usual, and this shows just how difficult it will be for the rest of us to get our economies going again.

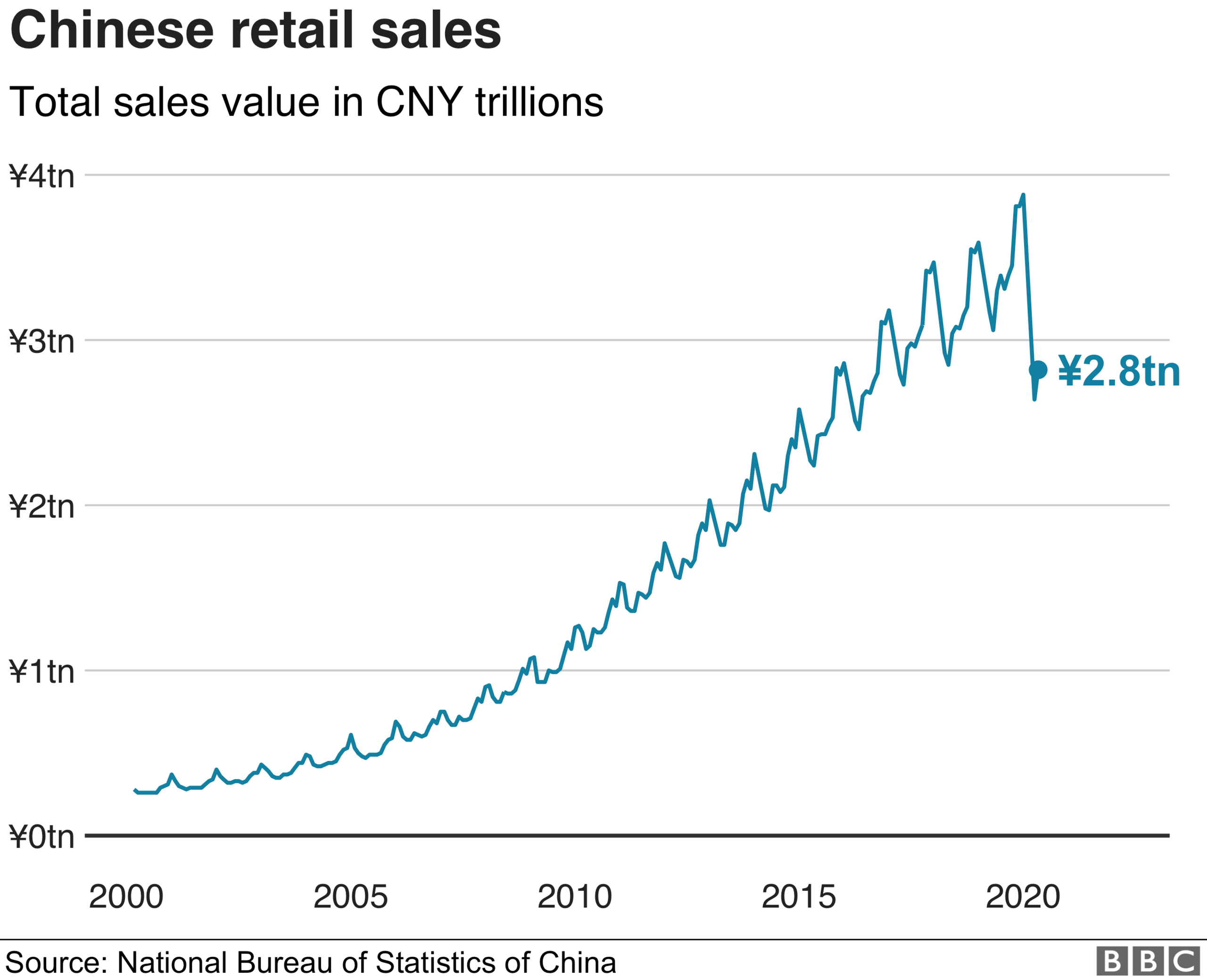

Recent retail sales figures show just how difficult it is going to be to get people into shops and buying things.

Sales were down 7.5% in April - better than March - but nowhere near where they need to be for the economy to be running on full cylinders. Many Chinese people are still worried about a second wave of infection, and they're not spending as much as they used to.

It's no wonder China has abandoned it's growth target this year - the government knows it will be hard to forecast just how deep this crisis has become.

Rising unemployment

Compounding all of that - are the all-important unemployment figures - which officially came in slightly higher in April than in March, at 6%, edging closer to historical highs.

But most economists say the real number is much worse.

The "true level of unemployment is likely double this", given that around a fifth of migrant workers haven't returned to the cities, says the think tank Capital Economics.

Even China's hard-line Communist mouthpiece the Global Times - typically the Chinese economy's biggest cheerleader - has pointed out how dire the employment picture is.

It is saying that this year "it will be nearly impossible for Chinese employees in the private sector to earn as much salary as they did in 2019," as small businesses have had to fire employees or cut staff.

It's going to get worse before it gets better.

Some 85% of private enterprises will struggle to survive over the next three months, writes Prof Justin Yifu Lin of Peking University, citing a Tsinghua University survey in March.

"Bankruptcy of enterprises will lead to an increase in unemployment," he adds.

2020 was meant to be the year China would eliminate absolute poverty

Granted, many Chinese people are employed by state-owned enterprises, and China's economic system is able to absorb the ranks of the unemployed better than the US.

Chinese people have more savings, better family support, and many migrant workers also have land back home that they can rely on for basic needs and even sustenance in the very worst of circumstances.

"You will see a great transition of migrant workers going back to their villages where they have their own piece of land," Wang Huiyao of the Centre for China and Globalisation tells me.

"Yes, there will be some hardships, but people outside of China probably don't understand how we view hardships and difficulties - which Chinese people just experienced not too long ago when China was very poor. "

The current economic environment is the most challenging China has faced in recent years

This time it's different

The Communist Party has always stated a growth target to achieve as a way of signalling how well China is doing.

But clearly this time it's different: no target - so there's no getting away from the fact that the current economic environment is the most challenging China has faced in recent years.

Indeed, China has been through difficult economic periods before - the 1990s, for instance, saw huge numbers of people laid off.

The economy at the time was dominated by state-owned enterprises - they provided jobs for the bulk of the working population.

As the economy slowed down, they shed millions of workers - and unemployment rose rapidly, by one percentage point every year according to the National Bureau of Economic Research.

State-owned enterprises went from employing 60% of the working population in 1995 to 30% in 2002.

But China recovered, and the private sector stepped in to hire young people.

China's workers may be working again but "the rest of the world is in an economic funk," says George Magnus

This time, it's different and the private sector is also under pressure, says economist George Magnus, associate at the China Centre, Oxford University. "No one was talking about trade wars at that time. The great offshoring of manufacturing to China was underway.

"Now, the rest of the world is an economic funk - so there's no consumer demand, and nothing in terms of foreign trade. All of the headwinds that China was facing before the pandemic have been compounded by the coronavirus."

'Chinese dream' under pressure

For the last 40 years, China's Communist Party has been able to promise a simple contract to its citizens: we'll keep your quality of life improving and you fall in line so that we can keep China on the right path.

It is the social contract that China's leader Xi Jinping crystallised as the "Chinese dream" when he announced it in 2012.

The Covid-19 crisis has become a major threat for social stability in the country

2020 was meant to be a pivotal part of that grand plan - the year China would eliminate absolute poverty, raising the quality and standard of life for millions of people.

But the coronavirus could be putting that social contract at risk.

Arguably more than any other economic crisis in the Chinese Communist Party's history, this health crisis has become a major threat for social stability in the country.

Millions of young people may not be guaranteed the same degree of success that their parents' generation has seen. Keeping that contract of wealth, employment and stability is key to the Chinese Communist Party's legitimacy.

Which is why economic recovery for China is so critical - and not having a growth target gives the government much needed flexibility to work out a plan.

- Published17 April 2020