Coronavirus: How 'immunity passports' could create an antibody elite

- Published

Covid-19 immunity passports could be used as a way to date without social distancing

Governments around the world are testing citizens for coronavirus antibodies, to work out whether people have had the deadly Covid-19 disease.

Some countries are setting up so-called "immunity passports" and others may follow suit.

The idea is that a passport would certify that you have had coronavirus and will not carry or contract the disease again, opening up a way out of lockdown restrictions for the holder.

But is this theory correct? And will it create a group of antibody-carrying elite who can date, travel and work as they wish, while others are still limited by health precautions?

'I know I'm clear, we should meet!'

Pam Evans, from Aberdeen, has just had a rude awakening to the new reality of internet dating. She says that a man who was interested in meeting her took a novel approach.

Pam Evans does not want to break lockdown rules by meeting men who think they are immune to Covid-19

"I had one guy at the weekend: 'I've just been tested last week for Covid so I know I'm clear, we should meet up' And I said: 'Oh no, absolutely not'... he became just absolutely abusive straight away."

Pam's hopeful date was trying to take advantage of his apparent negative coronavirus test result as a reason to break lockdown rules to visit her.

Is this a sign of how those who get a certificate stating they've already had coronavirus might use their privileged position in society?

In New York, people are using antibody tests - showing that they have been exposed to the virus and have recovered - as a way of suggesting they are safe to date.

New Yorkers have been going to testing centres where blood is taken to test for coronavirus antibodies

They are photographing positive test results to use as a kind of improvised "Covid-immunity passport".

If you have antibodies, the theory goes, you will not get the disease again.

Dating aside, what if we could decide who is safe to return to work or get on an aircraft? For those people. the Covid-19 lockdown could be over.

'Immunity passports'

The idea behind immunity passports, is that of a certificate confirming that you have had Covid-19. It could be used to enter places that those people without one are barred from.

To get one, you'd have to test positive for antibodies created after exposure to the virus.

A mock-up of a Covid-19 immunity passports - a way to avoid quarantine after flying?

Estonia is building an "immunity passport" system, and Chile is also planning what it calls a "release certificate", following such principles.

Tavvet Hinrikus, co-founder of the money exchange firm TransferWise, helped in the development of Estonia's phone app-based system.

"There are areas where I think it's a no-brainer we should use this, like… who takes care of our elders; can I go and see my parents?

"If immunity as a concept exists, then I think people who have immunity should be cleared to work with elders, or the same for frontline workers," he says.

Estonia's Covid-immunity passport uses mobile phone technology to identify users

Other apps are being developed to display antibody - and potentially immunity - status. One example is Onfido. Its co-founder, Husayn Kasai, says some US hotel chains are now accepting immunity passports via an app.

"It's predominately for guests who want to access some of the services, be it the spa or the gym, where social distancing isn't an option."

Antibody elite

But could there be a sinister aspect: the potential for a supposedly Covid-immune elite to develop?

Chinese shoppers use an app to show they are healthy before enter a shopping centre: Could immunity apps be used in the same way?

Robert West, professor of health, psychology and behavioural science at University College London (UCL), fears a "divisive society".

"You can imagine a situation where if you can get hold of some sort of certification, it will open up doors for you that wouldn't be open to people who can't have that certification.

"It could create a multi-tier society and increase levels of discrimination and inequity." Prof West also warns that the entire premise of immunity might be on shaky ground.

"It wouldn't be based on solid scientific foundation. It would be based on a probability that you may or may not be susceptible [to coronavirus] yourself or may or may not be in a position to pass the virus onto other people.

"It would be to the detriment of sectors of society, really being driven by commercial pressures."

Covid-immunity passports could mean travellers no longer feel they should wear masks

Prof West envisages a point where people with recent antibody certificates would be able to work with vulnerable patients in healthcare roles, or that firms might use their workers' immunity passports as a way of competing with other companies.

But he believes there's not enough evidence to show that having antibodies is a reliable way to tell how likely you are to catch or pass on the virus.

'She's OK, she has antibodies'

The air travel sector has been hit particularly hit hard by the pandemic and John Holland-Kaye, chief executive of Europe's busiest airport, London Heathrow, wants all countries to recognise antibody certificates.

"What you really need [is to know that] your health passport... is going to be accepted in the country you are going to, and you'll be allowed to return home safely without having any kind of quarantine."

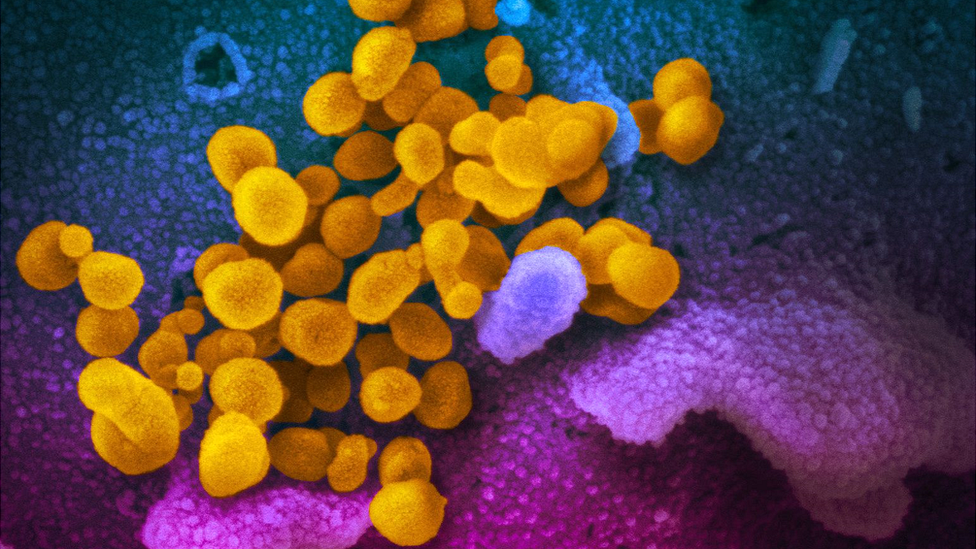

The Covid-19 virus under the microscope

Carmel Shachar, of the Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology, and Bioethics at Harvard Law School in the US, fears that people may actually try to catch Covid-19.

A scenario she worries about is: "If you want to go back to work, you're going to have to contract a deadly disease, one that we don't actually want you to have, from a public health point of view or from an individual point of view."

She also worries about privacy. "If my employer can demand medical information about me, have I had Covid, do I have antibodies - are they allowed to do so? If they have that information, are they allowed to share it?"

The commercial benefits of publicising this information for certain industries are obvious, Ms Shachar believes. "If I work at a restaurant, can my employer tell every customer who walks in the door: 'Oh don't worry, she's OK because she has antibodies'?"

The US has the highest number of confirmed Covid-19 infections in the world

Ms Shachar thinks known immunity could be of significant benefit. "You might say, for healthcare workers working with Covid patients, or nursing facility workers... we do want to see immunity."

She says that people really want to get back to how things were before the pandemic, or a "new normal" that is close to it, and are prepared to make compromises.

Testing questions

Getting to that "new normal" as quickly as possible is the target for governments around the globe, Many find antibody-testing the entire population a tantalising idea where infection rates are high.

In Germany, the country's disease control and prevention agency, the Robert Koch Institute, is conducting large-scale random antibody testing.

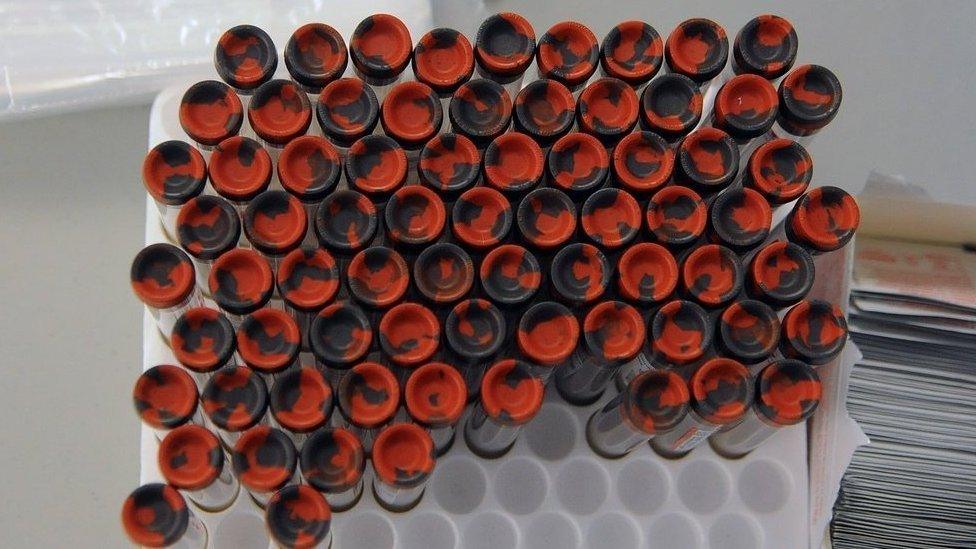

Antibody test blood samples: Countries are gearing up to offer mass antibody tests

But questions remain about the accuracy of some of these tests. Research published in May by the US-based Covid-19 Testing Project, external found that 12 antibody tests were accurate between 81-100% of the time.

While the US Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC), external has warned that some antibody tests could incorrectly state you had antibodies - up to half the time. Meaning those who'd never had Covid-19 could mistakenly think they had immunity, and might then act riskily because of this false sense of security.

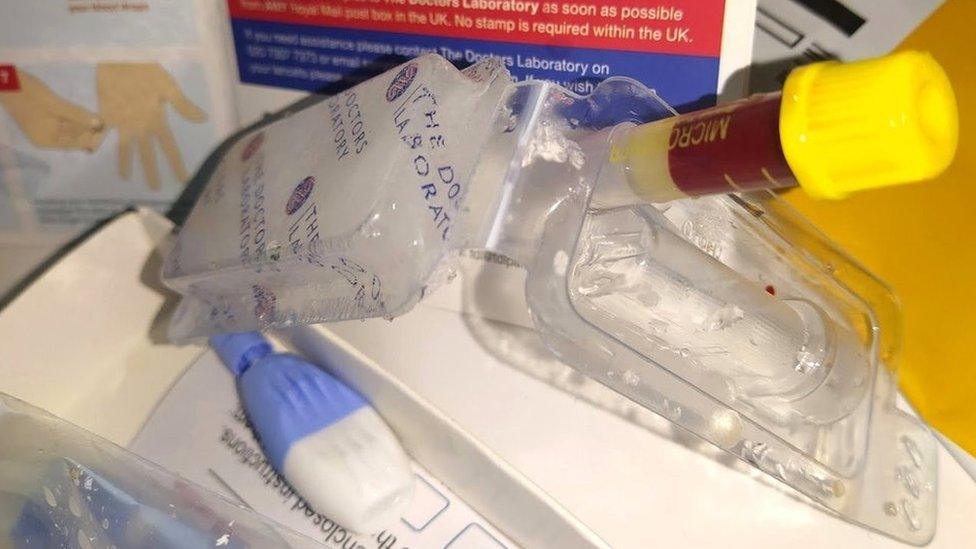

Home finger-prick kits are being used to send blood samples to labs that test for Covid-19 antibodies

And even if the test correctly identifies that you have antibodies, does that mean you are actually immune? The World Health Organization (WHO) has expressed its doubts, external.

In the UK, for example, concerns were voiced by 14 senior academics in a letter published in the British Medical Journal at the end of June, saying that antibody tests for UK healthcare staff were being rolled out without "adequate assessment".

US researchers have found a wide range of accuracy for antibody tests

Back in Aberdeen, Pam is similarly unconvinced by the antibody testing argument.

"We don't know how long this immunity could last for. We don't know if it is 100% right if you've had those symptoms. There's no harm in meeting somebody and sitting and having a coffee in a park," she says.

"I'm not someone who'll kiss on the first date anyway. So to me, having that two metres apart means that a guy can't lunge on you for once!"

This article featured interviews broadcast on Business Daily, on the BBC World Service.