Saudi Hajj coronavirus curbs mean 'no work, no salary, nothing'

- Published

With his head in his hands, Sajjad Malik sounds dejected. The taxi booking office he manages near Mecca's iconic Grand Mosque, the Masjid al-Haram, is empty. "There's no work, no salary, nothing," he says.

"Usually these two or three months before the Hajj (annual pilgrimage) me and the drivers make enough money to last for the rest of the year. But now nothing."

One of his drivers, Samiur Rahman, part of Saudi Arabia's largely foreign private workers, sends the office status updates from the roads around the popular Mecca clock tower. The sea of pilgrims is missing - they usually line the streets, dressed in white, with umbrellas to protect themselves from the intense heat.

Today the drivers' people-carriers are void of passengers and the city looks like a ghost town. Sajjad's drivers send him videos of the pigeons filling the roads instead.

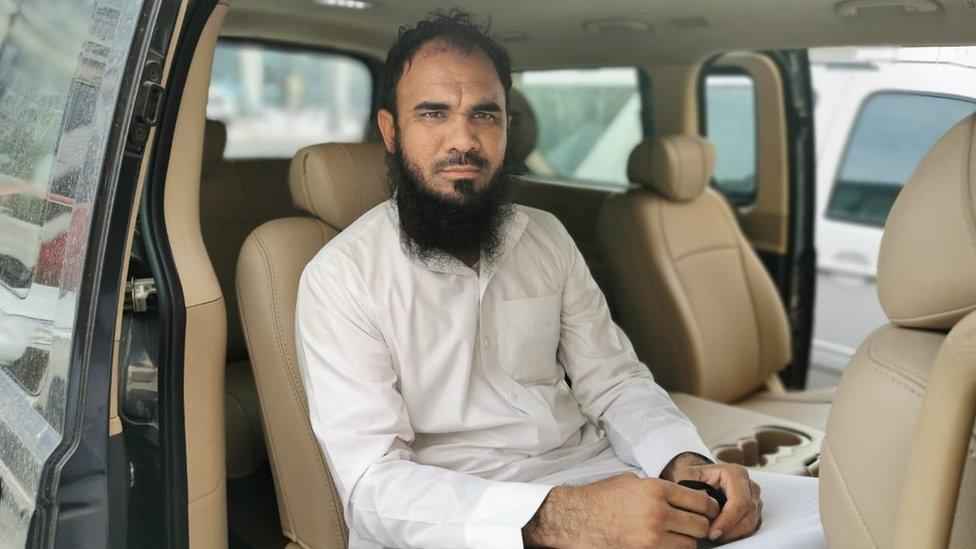

There are few passengers for taxi driver Samiur Rahman this Hajj

"My drivers have no food and now they are sleeping four or five per room, in rooms designed for two," says Sajjad,

I ask him if he is receiving any government help. "No, no help, nothing. I have savings, which we are spending. But I have a lot of staff - more than 50 people were working with me - and they are suffering.

"One of my friends called me yesterday, saying, 'Please I need some work, I don't even care how much you want to pay me.' Believe me, the people are crying."

There are severe restrictions in place for this year's Hajj. Saudi Arabia has seen one of the biggest outbreaks of coronavirus in the Middle East and has said the two million pilgrims who normally come from around the world to Mecca will not be allowed to do so, in a bid to limit the spread of Covid-19.

Only those already living in the country will be allowed to perform the Hajj - taking the number down to just 10,000.

Workers sanitise luggage in a Mecca hotel lobby

Pilgrims will not be able to freely drink from the holy Well of Zamzam, the water will all have to be bottled individually. And when it comes to the stoning of the three pillars in Mina, symbolising the rejection of the devil, the pebbles will have to be sterilised.

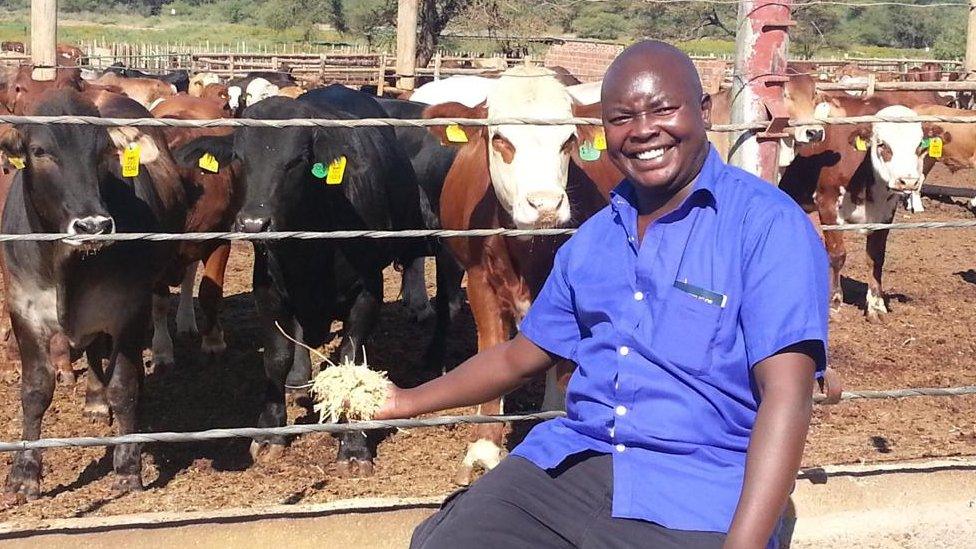

Away from Saudi Arabia itself, the huge influx of hungry pilgrims usually leads to lucrative import orders for livestock from neighbouring countries like Kenya - many of whose farmers now have herds of unsold cattle.

"The livestock subsector in Kenya is big. It's the mainstay for most of the households in the country, and a way of life for most farmers, especially during the Hajj period," says Patrick Kimani from the Kenya Livestock Producers Association.

Kenya now has thousands of unsold cattle due to the limitations on this year's Hajj, says Patrick Kimani

On average, his members export 5,000 head of cattle to Saudi Arabia for the Hajj, he says. "Farmers are now diversifying in to cold storage and local markets.

"We are concerned that it could decimate local cattle prices because all that extra produce could be dumped at cut price to local buyers for a quick sell."

Hajj dates back to the life of the Prophet Muhammad 1,400 years ago and there have been few limitations like this in its history.

What is the Hajj?

Making the pilgrimage at least once is one of the Five Pillars of Islam - the five obligations that every Muslim, who is in good health and can afford it, must satisfy in order to live a good and responsible life, according to Islam.

Pilgrims gather in Mecca to stand before the structure known as the Kaaba, praising Allah (God) together.

They perform other acts of worship too, renewing their sense of purpose in the world.

The shock of a sudden withdrawal of an age-old source of income is also leaving many tour companies struggling.

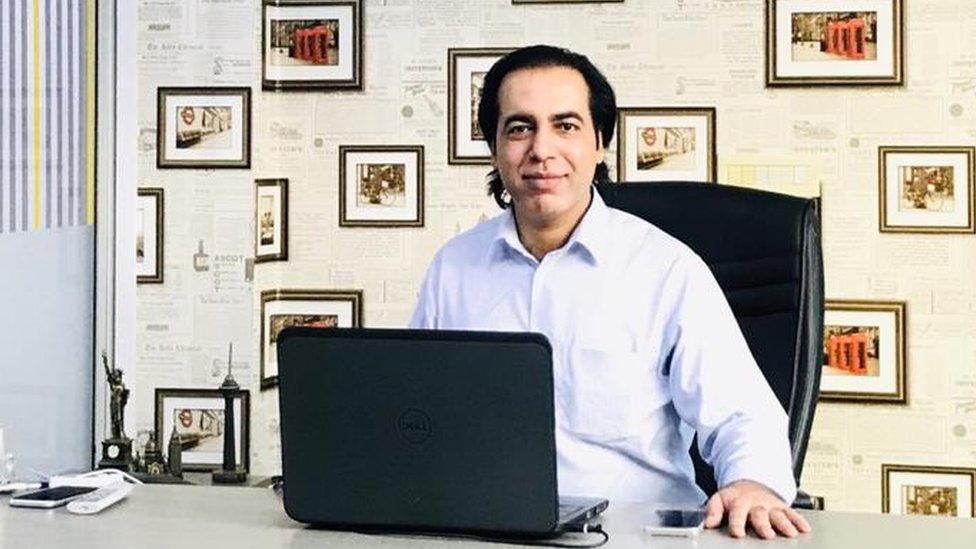

Last year, Pakistan sent the most foreign pilgrims to Saudi Arabia. But today in Karachi, Shahzad Tajj says his firm, Cheap Hajj and Umrah Deals, is on the brink of collapse.

Karachi travel operator Shahzad Tajj says he's been forced to sell property and other assets to survive

"Basically, business is zero. Even other travel-related activities weren't going on. Like flights, logistics, deliveries - so there was nothing to sell. We were not, frankly, totally prepared for this.

"We had to downsize our staff to minimal numbers. Time has now forced us to sell our assets, cars and some property, to just get through this stage at least. I help out some of my team with emergency funds, but that's all I can offer for now."

Restrictions this year are putting a large financial hole in the cities of Mecca and Medina, which receive billions of dollars worth of business from the travelling pilgrims.

"Although most of the cost to the Saudi government of hosting the Hajj will be saved this year, Mecca and Medina will lose out on around the $9bn-$12bn (£7bn-£9bn) worth of business," says Mazen Al Sudairi, head of research at the financial services firm Al-Rajhi Capital in Riyadh.

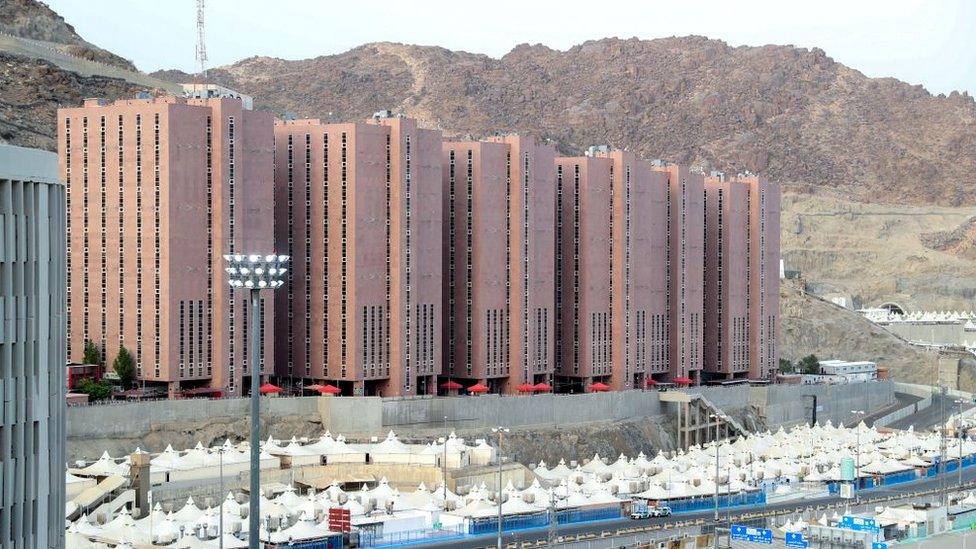

The usual pilgrimage is among the largest religious gatherings in the world (file picture from 2016)

This year's Hajj will look very different

Mr Al-Sudairi says the government has stepped in to help. "Maybe the small and medium enterprises were suffering, but the Saudi central bank is trying to support this segment, to give them relief, by deferring their loans for a further two or three months.

"We believe that we are facing a recovery period - we think the worst is behind us."

More than 80% of Saudi Arabia's national income comes from oil but prices have plummeted, forcing the country to diversify. Yet things haven't been going so well, according to Alexander Perjessy of Moody's Sovereign Risk Group.

"The government announced in March 2020 it would postpone collection of various government fees, as well as Value Added Tax, for three months. [But] this is not going to avert a recession in the non-oil sector of the economy - we think it will contract by about 4%," he says.

Pilgrims' tents in Mecca, ready for this year's Hajj

In Mecca, despite the empty bookings screen in front of him, Sajjad Malik does not want to return to his native Pakistan.

Saudi Arabia has served as an economic last-chance saloon for those in neighbouring countries who were struggling to earn enough.

"Working in Saudi for over eight years has allowed me to provide for my children and family back home. We get free medical benefits, and when the Hajj does happen, there are great earnings," he says.

"The labouring community are struggling now. But this country is still number one for me, praise be to God."

- Published22 June 2020

- Published25 June 2020