The headphones that even a DJ can't break?

- Published

DJ and broadcaster Anne Frankenstein

Before the pandemic hit Anne Frankenstein would be DJ-ing in bars or clubs most Friday and Saturday nights.

She laughs when asked if she misses it: "Not really, I kind of prefer the quiet life. I think I was playing a few too many gigs before lockdown. It's been nice to just enjoy music at my own pace."

Fortunately for Anne she has a day job - her mid-morning show on Jazz FM.

As well as making life hectic, those gigs took a toll on her kit, in particular headphones. She has "completely destroyed" headphones in the past through overuse and crushing them by accident.

Having learnt those expensive lessons, she doesn't spend much on headphones for work.

"I just get a nice cheap, robust pair of headphones, that isolate the sound well enough so I can hear adequately to DJ."

One of the reasons headphones can be delicate is that they have several moving parts inside. In fact the principle behind those moving parts has not changed much since speakers first emerged in the early 20th Century.

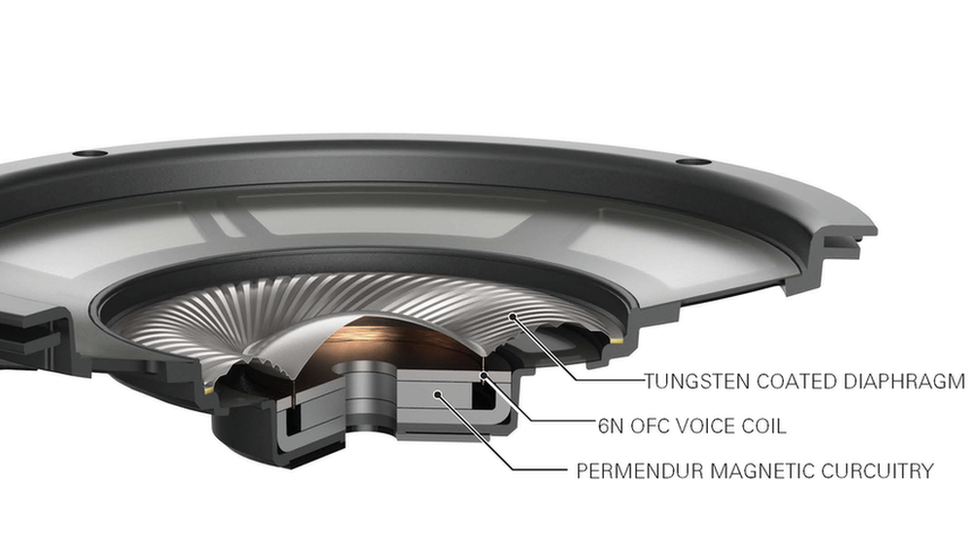

A diaphragm, coiled wire and magnets are at the heart of most headphones and speakers

By passing an electrical current through a coil of wire placed near to a magnet, you can make the coil move. Attach a thin sheet of material (diaphragm) to that coil and the vibrations will make sound.

The so-called moving coil system has become much more sophisticated over the years. Better materials and clever electronics have improved the sound quality, and speakers have shrunk to a size that can fit into the ear.

However, there are still multiple moving parts in modern headphones, which can be broken.

Making headphones more robust is just one of the promises of xMEMs, a Silicon Valley firm that thinks its technology can revolutionise the headphone market.

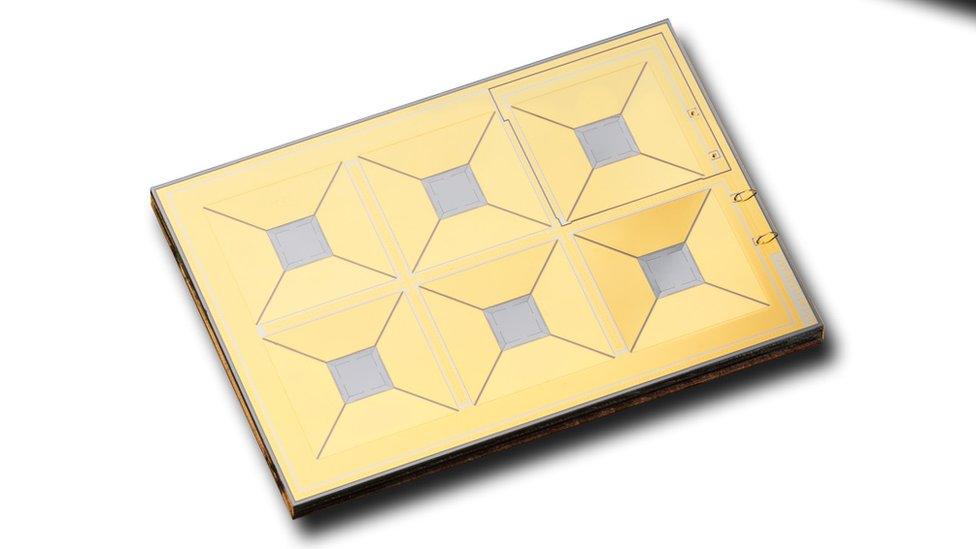

At the heart of its tech is something called the piezoelectric effect. If you bend some materials, they produce an electric current and the reverse is true as well, if you pass an electric current through them they bend.

The bendiness has been exploited for years to make sound, but that sound has been pretty unsophisticated - it's often used to make buzzers.

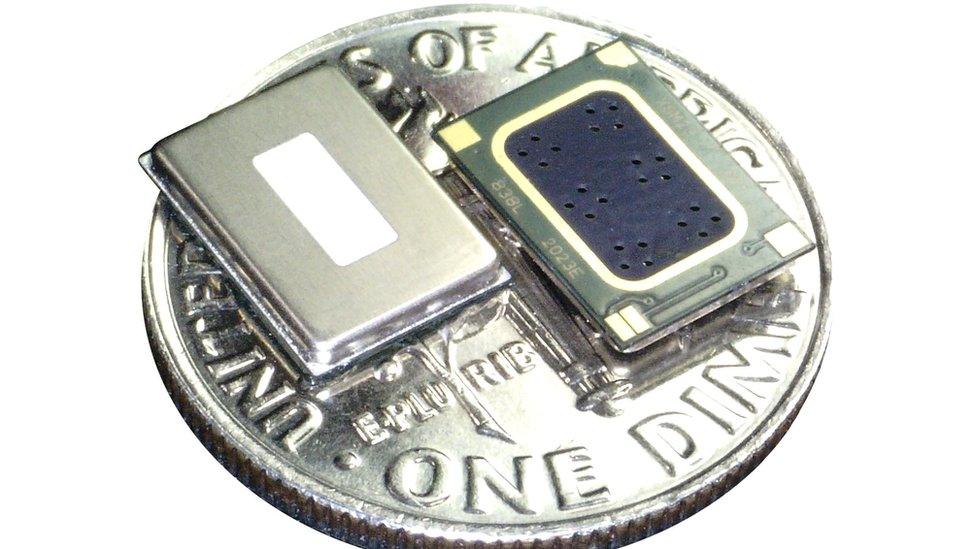

xMEMs has put six tiny speakers on one chip

Recent developments in materials have changed all that. Silicon Valley-based xMEMs has refined the technique and says its speakers can match the very best sound produced the traditional way.

Their speaker is very small and can be produced in the same way as a computer chip. Six of the little speakers can sit on one chip and, with everything in one place, the device is robust and waterproof.

"You're getting next level mechanical shock resistance," says Mike Housholder, VP of marketing at xMEMS. "You can drop a tray of these on the earbud assembly line, they're not going to break."

They also promise to be more effective at noise cancelling he says, a feature important for those who fly or use other public transport.

Mr Housholder expects the first headphones using his company's technology to hit the market next April.

xMEMs speakers can be produced in the same way as computer chips

It's an "exciting" technology says Kelvin Griffiths, an audio engineer, who has been working with speakers and headphones for more than 20 years and now runs his own consultancy.

While he can see the potential advantages of such a system, he is also cautious. He points out that traditional moving coil speakers have been evaluated over decades, the kind of scrutiny which xMEMs is yet to go through.

"Any advantage would need to be clear and useful, because moving coil loudspeakers are just one of those technologies that just seems to be a good fit for so many applications," he says."

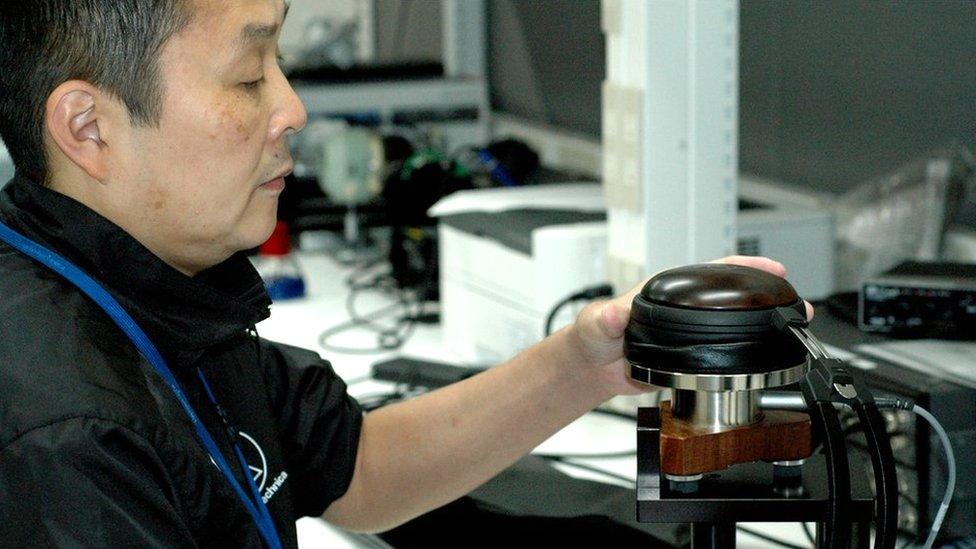

Hiromichi Ozawa, is the manager of headphone research and development at Audio Technica, Japan's biggest seller of headphones (with cables, rather than wireless). He has worked in product development for more than 30 years.

During that time he has seen a multitude of innovations. He remembers in the 1990s developing a wooden casing for mass market headphones.

Hiromichi Ozawa has been working on headphone development for 30 years

"Wooden housing had interesting acoustic qualities and added a certain aesthetic pleasure to the listening experience.

"We wanted more people to experience this unique, natural sound," he said.

While he appreciates the potential of new technology, he likes the traditional moving coil system which has a "simple construction" but "powerful results".

Mr Ozawa says the real challenge for headphone makers is to maintain sound quality, while building in extra features, like a wireless connection.

In particular, he says reproducing intricate instrumental music is a key test for speakers. So, for thirty years he has been using Mozart's piano sonata, played by Ingrid Haebler, to test the sound quality of new headphones.

Different materials give a slightly different audio quality

But does the average buyer really care much about what is going on inside their headphones?

Not according to Paul Noble, who owns the headphone shop Spiritland, in London.

"It's more about wearability, performance, price, design - not the internals," he says.

He has sold hundreds of headphones since opening his shop in October. Prices range from £100 to more than £5,000.

"The big big trend which has overwhelmed the headphone market is Bluetooth and cordless. People just wanting to be totally free of the cords and have headphones for exercising or whatever."

As for Ms Frankenstein she likes to check reviews before buying and also pays some attention to what the headphones look like.

"I don't want to look like a massive dork," she laughs.