Why Biden's intervention on Brexit matters

- Published

- comments

For two years British cabinet ministers have privately warned about the impact of a third party in the Brexit talks - the US Congress.

On the face of it, arms of the US government should have little impact or influence on UK decisions. But US politicians have always maintained a keen interest in anything that might impact on the Good Friday Agreement, as the US was one of the guarantors of peace in Northern Ireland.

For its part, the UK has made reaching a trade deal with the US a top priority. The freedom to do such a deal with the US was one of the motivating forces behind Brexit. Wanting that trade deal lay behind MPs' rejection of Theresa May's original proposals that would have seen the UK stay closely aligned to EU economic standards and rules. And that in turn lay behind Boris Johnson's subsequent ascent to Number 10.

So both sides have good reason to pay close attention to what the other says and does.

The US House of Representatives turning majority Democrat in 2018 was the trigger for concern among members of the British cabinet. Key figures in the Congressional Irish lobby, who had hosted Sinn Fein's Gerry Adams in DC for example, were appointed to important positions overseeing US trade deals.

Since then, Irish diplomats in the US have cultivated the cross-party Irish lobby in Congress, and persuaded them to see the Brexit "backstop" provisions as essential for the protection of peace in Ireland.

'EU out, US in'

The Trump administration has taken a slightly different approach. It has been keen to do a US-UK trade deal as quickly as possible. And it wants the deal to be far-reaching, pushing for the UK to detach itself from EU food and farming standards that America views as "protectionist", in other words, designed to block foreign competition. As the Vice President Mike Pence himself put it last year: "when they [the EU] are out, we are in".

Mr Pence went as far as to lean on the then Irish leader Leo Varadkar, asking him to show more flexibility over Brexit. In the end the Irish accepted a "consent mechanism" through which the revised backstop could end after four years.

This is not to say that the Trump administration would acquiesce in damaging the Good Friday Agreement. The President's trade representative, Robert Lighthizer, made clear over the summer, that there would be "no point" negotiating a US-UK trade deal that led to borders going up in Ireland, because it would not pass in Congress. But this US administration has been more willing to accept British protestations that its plans will not harm the Good Friday Agreement. This is the case currently being put in the US capital by Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab. And in any case the timing is not right for the Trump administration to start putting pressure on Ireland again now.

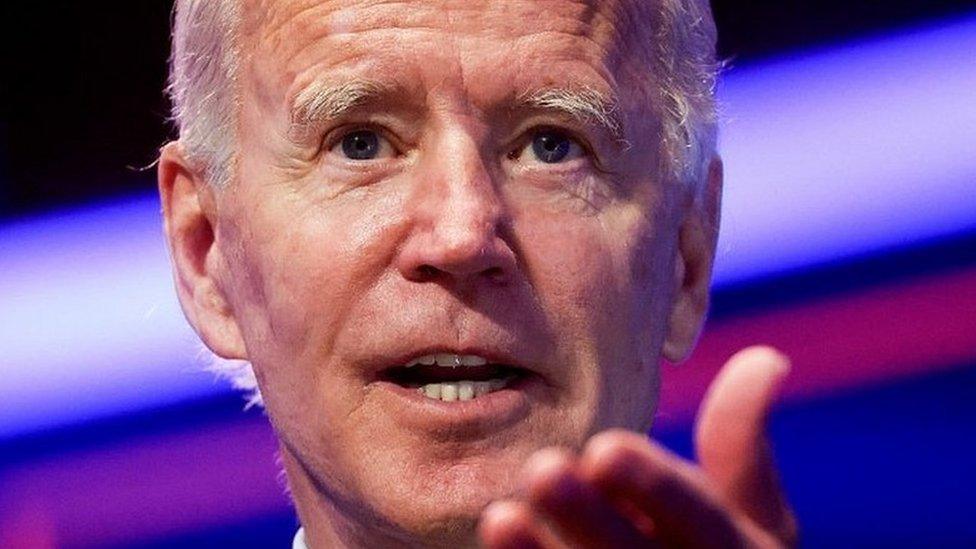

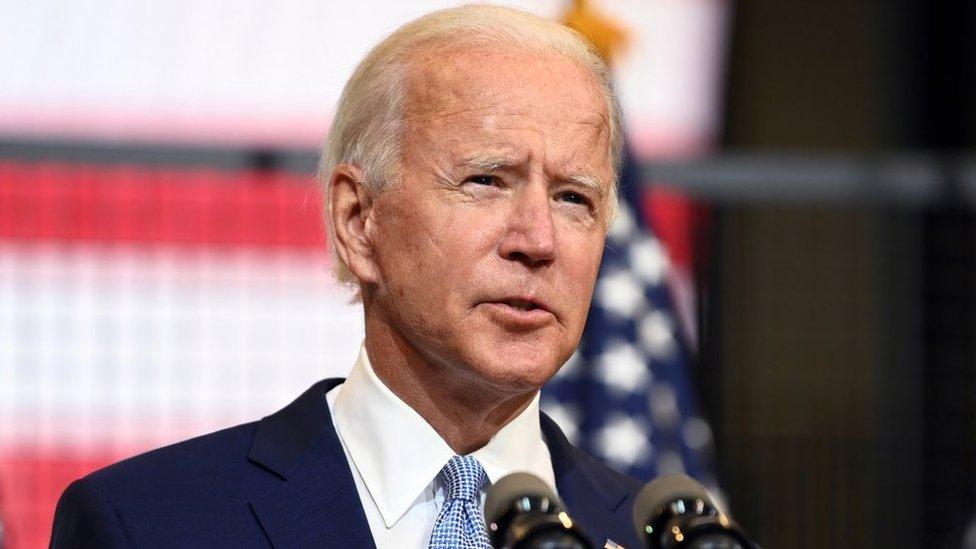

Letter to Boris

But now there is the possibility of a President Joe Biden. Trade deals do not seem to be his priority. He is on the record as a Brexit-sceptic. And he has Irish roots. The key point here is that the Congressional Irish caucus has now publicly questioned the UK's plan to renege on aspects of the Northern Ireland protocol. One of Mr Biden's advisers, the chair of the committee overseeing trade and the speaker of the House, Nancy Pelosi, have all issued statements saying Congress would veto a deal if the UK broke international agreements. Congressional leaders have written to Boris Johnson to make their views clear. They have specifically dismissed the PM's argument that this has been done in order to protect the Good Friday Agreement. Now Joe Biden has associated himself with that letter to the PM.

Number 10 may no longer be quite as keen on a quick transatlantic deal as it was. There have been difficulties around food standards and farming practices. But events in DC have clearly complicated things. And that is well before result of the US election.

There are obvious consequences should Mr Biden win in November, all the more so if the Democrats also achieve a sweep of Congress. Come January, if the UK has reneged on that international agreement, the country could be facing diplomatic difficulties with US, as well as with the EU, on top of a possible no-deal Brexit and the challenge of the pandemic.

- Published17 September 2020