'I altered my personality to fit in at work'

- Published

The BBC spoke to four diversity champions

The lack of ethnic diversity at the top of UK companies is coming under increasing focus, with calls for change from big business groups and investors.

Surveys continue to show that black, Asian, or minority ethnic (BAME) people are under-represented in senior positions., external

But some succeed, and then turn their drive and passion to helping others. The BBC has spoken to four of them.

'I had adapted who I was to fit the environment'

Pavita Cooper said she altered who she was to fit in

Pavita Cooper runs More Difference, a recruitment and consultancy firm that promotes diversity.

Working at blue-chip firms for more than 25 years she never felt discriminated against.

But after she left, she realised she had been altering her personality to "fit in".

"I had adapted who I was to fit the environment," Pavita says. "I presented a version of myself that would fit in with them."

"I'm a Sikh, and faith is important to me," she adds. "But I made an assumption I should be just like them."

Despite under-representation, she says people with an Asian background tend to have an easier time getting to the top of large firms than black people.

"If you're black, generally the experience is worse," she says.

What's more, there's a "hierarchy of race", she says, with "very black women" having the toughest time of all.

One way to solve this problem is to make ethnic minority pay gap reporting mandatory, to force executives to act, she says.

'I had to put in a lot more effort to get my foot in the door'

Funke Abimbola says she missed out on job opportunities because of her African name

One black woman who managed to get into high-flying jobs in the UK is lawyer, consultant, and campaigner Funke Abimbola.

She experienced discrimination working in the legal profession, even though she had what she describes as a "privileged" upbringing.

"I had to put in a lot more effort to get my foot in the door," she says.

She refused to change her African name, even though she says she missed out on job opportunities because of it.

And she says she had to deal with micro-aggressions - everyday slights and indignities - on a daily basis.

For example, a client once used a racial slur in a meeting. "When he said it, he knew I was black," she says.

As she climbed higher up the ladder, she was criticised as being "too assertive" by executives.

"White male leaders can't deal with it," she says. "They say I am 'over-promoting' myself."

She says black people in business face "systemic barriers" such as low expectations about their potential, and that because there are so few in top businesses, black people get scrutinised more.

You have to have "real steel" to progress, she says.

'You don't see a lot of people who look like me'

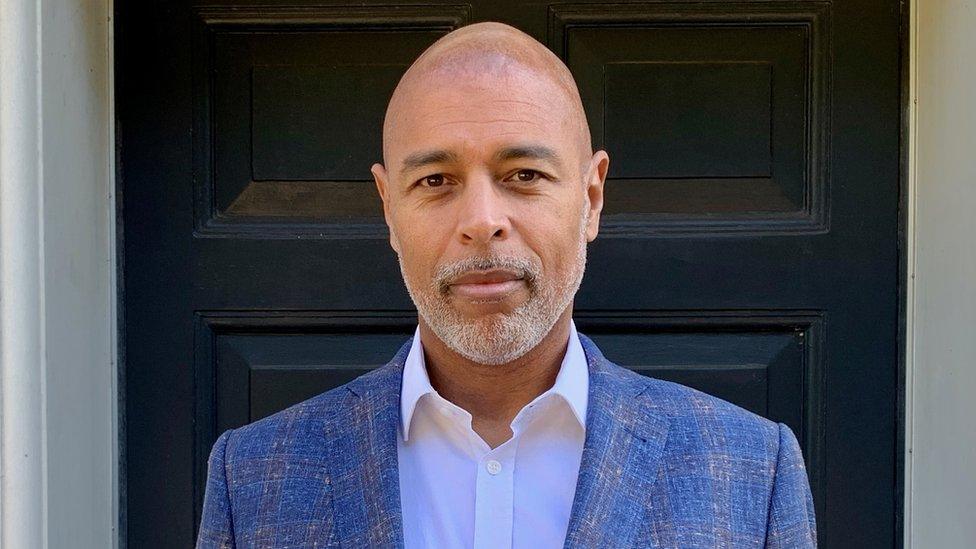

Dawid Konotey-Ahulu was told he wouldn't be joining a barristers chamber

Entrepreneur Dawid Konotey-Ahulu is involved in initiatives to try to improve workplace diversity.

He started out as a lawyer before having a successful City career, but says he faced extra hurdles compared with white people.

In the 1980s he was training to be a barrister and managed to get what's known as a "pupillage" - a kind of internship - at a Middle Temple chamber in London.

It is usual for such interns to be offered a tenancy at the chamber - a job - after completing this training.

But Dawid was told he wouldn't be in the running because there was already one black barrister there.

"The bar is shockingly unrepresentative," he says.

Dawid, who is one of the co-founders of consultancy Redington, said his time working in investment banking was less discriminatory.

However, black people are still under-represented in Britain's financial heart, he says.

"I spent a lot of time working with pension funds. You don't see a lot of people who look like me."

There are various obstacles to success for black people, which Dawid likens to "kinks in a hose". Once you sort those kinks out, the water can flow freely again, he says.

Obstacles include few mentors and role models for black children and numerous reasons executives give for not hiring and promoting black people.

"You have to say to 11-year-olds: 'You see those tall, shiny buildings over there [in the City]? There's a seat for you there'," he says.

Senior executives say the black talent pool is too small for senior positions - a situation which has become self-fulfilling - and that skin colour shouldn't matter, as they just want to hire the best people.

He says this argument only works if there is a level playing field to begin with - but there isn't.

He also says some senior executives use the BAME acronym as a smokescreen.

Firms can "muddy the water" by saying they are hiring BAME people, and yet can predominantly be hiring Asian people - who already have more representation in the City than black people.

'As human beings we need to be part of a group'

David Wallis says micro-aggressions knock people's confidence

There are also people working inside companies to try to change the situation.

David Wallis is a partner at accountancy firm Deloitte, and helped to launch the company's "black action plan", which aims to educate people within the company and to nurture black talent.

He too has experienced micro-aggressions from clients.

David's father is British and his mother is from Ghana, and his name comes from his father's side.

When he meets some clients for the first time there is an "audible gasp" because "I don't fit the stereotype of what a 'David Wallis' looks like", he says.

The problem with such reactions is the feeling of not being accepted, he says.

"As human beings we need to be part of a group," he says. "Micro-aggressions show you're not part of the group, and that can have wide-ranging consequences."

They can dent confidence, he says, and even contribute to mental health issues.

- Published5 October 2020

- Published1 October 2020