The forklift truck drivers who never leave their desks

- Published

Some warehouses are opting for remote-operated forklift trucks

During the pandemic, many of us have relied on having goods delivered to our homes more frequently than before.

But as Covid-19 spreads easily, the warehouses dotted along the world's supply chains have become potential hubs of disease transmission, says Elliot Katz, co-founder of Phantom Auto.

The solution, he suggests, is to reduce the number of people working in those environments. Take forklift operators, for instance - with remote-control technology they can now work off-site, controlling their machines from afar.

Phantom Auto technology is being used in around four warehouses, mostly on a test basis.

Some see this concept, teleoperation, as a stepping stone between traditionally driven vehicles and the truly autonomous ones of the future. But is it safe to drive a large truck or forklift device from miles away? And is it more economical than having a trained driver or operator on site?

When it comes to remote-controlled vehicles, teleoperation generally involves kitting out a car or truck with cameras and other sensors that feed information to a remote operator in a separate building.

Trucks for construction and mining can also be driven remotely

Multiple monitors provide a wide field of view so the operator can see what is around the vehicle. Generally, driving control is enabled by a joystick or steering wheel and pedals on the floor.

Some of the warehouses using Phantom Auto's technology fence-off the space where the remote-controlled forklifts work, says Mr Katz and the forklifts are also fitted with microphones so the operator can be warned should something be about to go wrong.

"If someone is behind that forklift and says, 'Hey, you're about to hit me,' the operator can hear it just like he's sitting on the forklift," says Mr Katz.

Among the other firms working in the teleoperation space is US start-up Teleo. It specialises in retrofitting construction equipment so it can be driven remotely. It has just started a trial at a quarry for an unnamed client. In this case, Teleo has adapted a large-wheeled loading vehicle so it can be controlled from an office on site.

In the future, a driver could sit in the office and remotely control a variety of vehicles nearby. That might mean fewer people would be employed on-site overall but Teleo argues it makes the role safer for the driver.

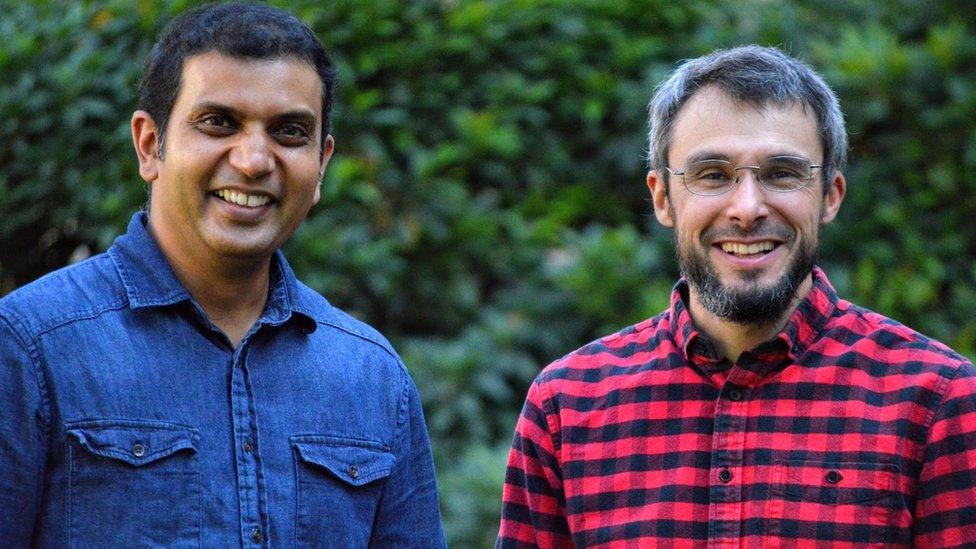

Founders of Teleo, Vinay Shet (left) and Rom Clement

Besides, there aren't enough heavy vehicle drivers to meet construction industry demand at the moment, asserts Teleo co-founder and chief executive Vinay Shet.

"We believe by converting an effectively hazardous job like this into an office job, we should be able to attract a wider pool of people," he explains.

Some argue that taxis and rideshare vehicles ought to be teleoperated, that way drivers could activate and remotely steer vehicles to customers when needed, rather than having to drive around a particular area of a city just hoping that someone will request a ride.

But the idea of vehicles driven like this is controversial for some. There's always the possibility a terrorist, for example, might try to hack such a system and use a teleoperated car or truck to kill people.

Remote-controlled trucks could ease a shortage of heavy vehicle drivers

Mr Katz and Mr Shet both say their firms have thought about this scenario and add that their engineers have introduced various steps to make a cyber-attack harder. For example, by encrypting communications between teleoperator and vehicle, requiring authorisation of drivers and automatically shutting down vehicles should they lose access to a reliable communications signal.

No-one can guarantee that such a system will never be hacked, though, points out Christian Facchi at the University of Applied Sciences, Ingolstadt. He and colleagues have studied the technical limitations and security risks of teleoperated vehicles.

"We have to reduce that risk," he says, referring to the prospect of a terrorist incident. Companies should make it as difficult as possible for this to happen, he argues, adding that standards governing the security of teleoperated vehicles should probably be set by a public body rather than firms themselves.

However, Dr Facchi does think that teleoperated vehicles may prove more immediately useful than autonomous ones.

This is also Mr Shet's position: "We can deliver a product today, not 10 or 15 years in the future."

The military has long been interested in remote controlled vehicles

And teleoperation could even accelerate the development of fully autonomous vehicles - so hopes the US military. A project at the US Army Research Laboratory involves using human teleoperators to train a wheeled reconnaissance robot how to drive across tricky terrain or hug the outline of a building as it scouts for danger in enemy territory.

"We'd like to be able to deploy a robot kilometres in front of the soldiers… to sort of provide that information, the intel we could send back before the soldiers have to enter that ground," explains researcher Maggie Wigness.

Staff training the devices steer them just like they would a small remote-controlled car. "If you know how to use a video game controller, you can pick it up," says Dr Wigness.

An artificial intelligence system then gradually learns how to drive the device itself, based on data from these manually controlled experiments. So far, the system has been trialled at US Army facilities including the mock town training area at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina.

In specialised environments where risk factors like pedestrians and communications interference can be more tightly controlled, remote-operated vehicles are already coming into use. But on public roads, such vehicles face plenty of challenges.

For one thing, it's pretty difficult to guarantee a 100% reliable communications signal across a wide area, says Dr Facchi. What happens if the signal cuts out just as the driver is remotely steering the vehicle around a busy corner, with pedestrians about to step on to a zebra crossing nearby?

"In an area where you have very bad network coverage," says Dr Facchi, "it might be a bad idea."