'I'm sick of influencers asking for free cake'

- Published

If people like my cakes then they can buy them, says baker Reshmi Bennett

"Why don't people want to pay for cake?" Professional chef and baker Reshmi Bennett often wonders why people she doesn't know will ask her to bake an Insta-worthy cake free of charge.

The London-based baker runs Anges de Sucre, and she's created a bit of an online storm by calling out social media influencers who've asked for freebies.

"I wrote this blog on Instagram because I'm sick of influencers asking for free cake all the time. After the pandemic it got worse and it started upsetting me."

Like many businesses during Covid-19, Reshmi has seen a change in her customers' behaviour. Although many people cut back on unnecessary purchases, her bakery was busy as people carried on ordering her celebration cakes.

Yet she also noticed influencers were asking for more freebies too. It's something she has done in the past - looking at the influencer and their posts, who follows them, how they engage with their audience, but says it didn't work for her.

"We have never had a sale off someone [saying] they saw our cake on someone's post or profile, it's always been through word of mouth, from paying customers."

Reshmi says using influencers did not help her cake sales

The influencer market is large and diverse. Businesses simply have to choose who they want to collaborate with based on what they see on the influencer's feed, what they wear or what they talk about.

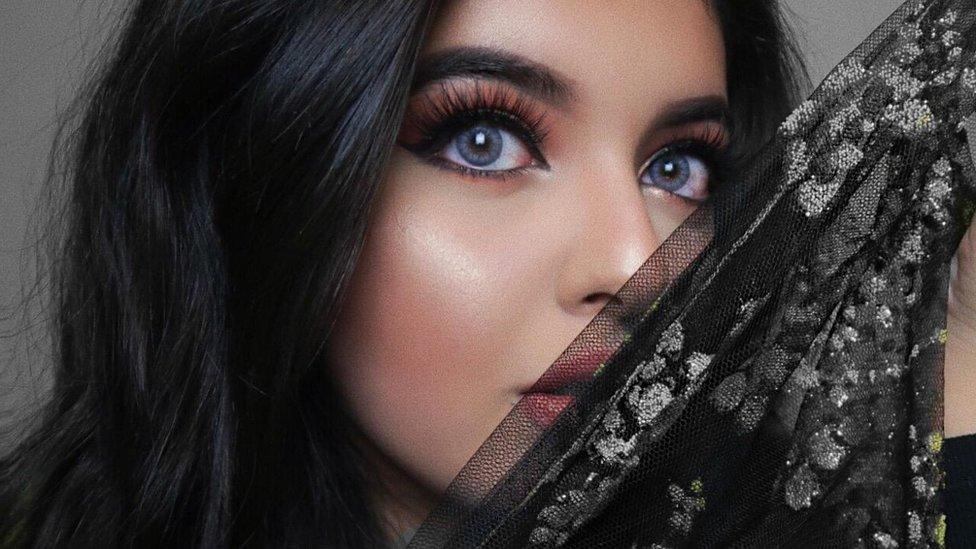

Beauty and lifestyle blogger Karishmua (Karishma Vijay) gave up a future career in medicine to be a full time influencer. With nearly 180,000 Instagram and 70,000 TikTok followers, her "brand influence" has been lucrative - but not without effort and hard work on her part, she stresses.

"For a post on my Instagram I can charge between £200-600 depending on how many hours I've dedicated to that post.

"If a cosmetics or skincare brand want me to create a tutorial using their products, I know that will receive hundreds or even millions of views on Instagram or TikTok. And I know I can make them at least £2,000 in sales."

"I charge between £200-600 depending on how many hours I've dedicated to that post," says Karishmua

Forbes predicts huge growth in the influencer space, and the market could be worth £11bn by 2022. With the sector being so diverse, what is more visible now is the rise of the micro-blogger - people with smaller, loyal followings and shorter content posts.

This is something Riz Kayaal, who runs an Eid and Ramadan decorations firm, has embraced. "We've worked with over 350 influencers and micro-bloggers and I've given away stock worth £15,000-20,000 as freebies.

"These small influencers and bloggers have been much better in terms of how they've showcased my product, how they've appreciated the product."

Riz says working with influencers who provide rate cards is the most productive way to operate. "They might charge £300 for two posts and an Instagram story, but they make it clear what they will do and how they can showcase the product."

Riz Kayaal says she's found working with social media influencers useful for her business

Brand and digital strategist Ashanti Akabusi has clients from the corporate and entertainment worlds at her company VirtuBrands. Much of her work is about building and strengthening clients' social media profile and brands - which often involves working with influencers.

"When it's the right influencer, they can be extremely impactful for a business." However, she understands that many do not have real influence they claim they do. "A lot of the backlash we're seeing is in response to an over-saturation of the market, and people calling themselves influencers when they probably don't have the right to do so."

She says the relationship between a business and an influencer can often be a positive one, but "the key is to choose the right influencer".

Many businesses haven't yet moved away from billboard advertising, but with a growing number of digital spaces to show off products, the arena is bigger. That means more space for ordinary people to work as influencers - like beauty blogger and business student Aisha Shaban. She says she's a reluctant micro-blogger (17,000 Instagram followers) but more importantly, is someone who never asks for freebies.

Aisha Shaban makes a point of never asking firms for free gifts: "I think it's disrespectful"

"If they reach out to me to collaborate, I'm more than happy to support the company by advertising them on my platforms, but I would never go out of my way to reach out to the brand because I feel like I would be taking advantage of their hard work.

"I think it's disrespectful for micro-influencers to ask small businesses for freebies."

Aisha has been offered paid sponsorship deals by big online fashion brands, which she turned down for ethical reasons. This, she says, is what helps a successful influencer to be authentic, and followers appreciate that honesty. If a big brand does something she doesn't agree with, she chooses not to work with them. With no financial commitment between them, that's easier to do.

With many businesses deeply affected by the pandemic, should influencers be utilising their power to help support various industries?

Travel blog Mrs O Around The World run by Ana Silva O'Reilly recently started a campaign for travel influencers to support the tourism industry. #PayOurWay wants influencers who have previously benefitted from travel freebies to help kick start the industry by paying for their next trip and blogging about it free of charge.

Also, the (somewhat controversial) #EatOutToHelpOut scheme was largely supported by food and lifestyle bloggers who championed restaurants, bars and cafes that were taking part.

Should influencers do more to show their worth to businesses in the future? Ashanti Akabusi thinks this is the way forward: "The influencers who are going to win are those who are experts in their field, and who have built credibility with their audience."

And what about baker Reshmi Bennett who just wants influencers to stop asking for free cake? "I'm as passionate about telling other cake makers to not do it. If everyone says no, someone is going to have to pay for cake at some point.

"We love influencers…as customers."