How much economic damage would a circuit-breaker lockdown do?

- Published

- comments

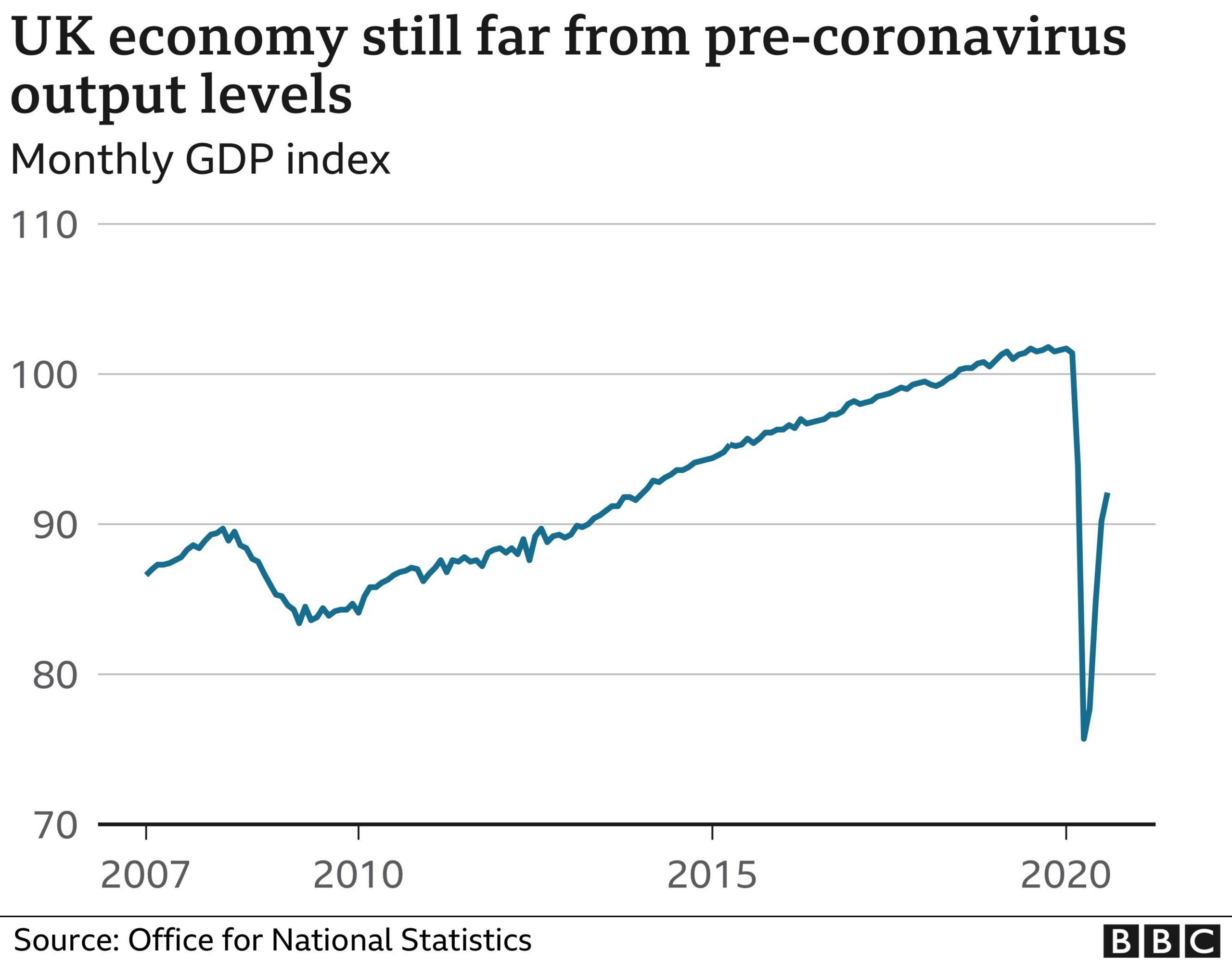

The April lockdown hit the economy incredibly hard. The economy shrank by a fifth, or 20%.

So a two week "circuit-breaker", which would be less intensive, could hit the economy by 5% or more, definitively sending an already slowing recovery back into reverse, and stretching out further the period of recovery.

It would probably lead to another quarter of shrinking growth, just as the technical recession from the first wave officially ended. It would not alone necessarily be a formal double-dip recession though, as the impact would be likely to be contained within one quarter.

Capital Economics calculate it would push the recovery of the economy back to pre-pandemic levels by a year to 2023.

Immediate impact

The hit would be less than April because important parts of the economy would continue to run. Including the half-term period might also help limit the economic impact.

Also the hit would be the additional impact on UK of a national lockdown in England over existing regional lockdowns in Merseyside or Northern Ireland. Still, there would be an immediate impact.

The National Institute for Economic And Social Research put the value of the hit to the economy at £15-20bn: "Preliminary estimates suggest that a return to April lockdown conditions for two weeks could cost between £15bn and £20bn in lost output. As in April the Government will choose how much of that to mitigate through public spending," it said.

Voluntary caution

If there was such a period then it might be reasonable to assume a period of full furlough scheme. That would cost £3bn in and of itself, but again it depends on who will claim on top of those already claiming.

Indeed, it is important to stress that we are not in a binary choice between health and the economy.

A World Bank study of 49 countries in the first half of this year showed that the biggest single factor behind the biggest hits to the economy, was the size of the outbreak, not the size of the lockdown.

Countries that tested lots of citizens were also protected from the fiercest falls in the economy. GDP is hit by mandatory lockdowns, but also by voluntary caution from risk averse consumers in countries where the virus is not under control.

So Niesr stresses of its £15-20bn number "that up-front cost must be set against significant potential economic benefits post-lockdown if it is successful in reducing the spread of the virus and restoring economic confidence".

Indeed, should the circuit breaker stop the virus from spreading out of control the expensive up-front cost could be a price worth paying for a shorter, more manageable pandemic later, especially if the test and trace system could be fully fixed in that time.

The problem though, is if a two week shutdown proves to be an over optimistically short period, which ends up needing extending without solving the problem.

That would break, not the circuit but the economy at a time when government borrowing is at a record peacetime level, and post- Brexit trading uncertainties loom.

There's no easy answer here.

- Published14 October 2020

- Published5 October 2020

- Published5 October 2020