'My parents had hearts of gold, they didn't deserve it'

- Published

In late March, Salvatore Forte's father woke up shivering uncontrollably.

"I've never seen him like that," Mr Forte says.

He called an ambulance to take his 80-year-old father to the hospital.

It was the last time Mr Forte would see his dad alive. He died alone of Covid-19 in New York hospital.

Two days later, his mother was also dead from the virus.

"My parents… had hearts of gold and the way this all happened, they didn't deserve it," he says.

Mr Forte's parents died within two days of each other

For Mr Forte, the loss was unimaginable.

A business owner, he is just one of many struggling through the pandemic in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, a racially and economically diverse neighbourhood a few miles from Manhattan with a population of around 80,000.

A closer look at the area reveals a snapshot of the terrible damage wrought by Covid-19.

Countless loved ones have been lost. Businesses teeter on the brink of ruin. Lives have been upended.

Running his small business was already hard "and is even harder now", says Mr Forte

Mr Forte not only lost his parents, he is fighting to hold on to the popular brunch restaurant and gift store he operates on one of Bay Ridge's high streets.

"Running a small business is hard enough before this and it's just even harder. And I don't know how many people are going to survive. I'm doing day by day," he says.

And he's not the only one.

The bar owners

Tony Gentile owns Lonestar Sports and Grill with his partner Tracy Blaise

Tony Gentile owns Lonestar Sports and Grill with his partner Tracy Blaise.

It sits near the busy retail intersection at 5th Avenue near 86th Street.

The Turkish diners, Chinese restaurants and Italian pizza joints hint at the neighbourhood's diverse population.

Lonestar, a Texas-themed pub with TV screens everywhere, is a reflection of the area's traditionally conservative white- and blue-collar community.

The bar closed its doors in March as New York City went into lockdown.

Ms Blaise calls that night "bittersweet". She remembers getting into a row with a regular who was angry at being told to go home. Her husband recalls feeling fearful for his staff.

How one neighbourhood in New York lived through the pandemic

"They have apartments and bills to pay, and student loans," he explains.

Initially, New York's bars and restaurants were only allowed to offer takeaway and delivery. So Lonestar, which once relied on alcohol sales to make money, pivoted to selling food.

For the family, it's meant all hands on deck. Their son Tyler now does deliveries - the main source of income for Lonestar since the health crisis began.

"They're definitely struggling a lot, I can tell," he says on his way to drop off an order.

With the reduction in sales Mr Gentile and Ms Blaise are finding it hard to meet all their expenses.

Bay Ridge is a diverse area

Lonestar has let go of half of its 21 staff and is struggling with rising food and cleaning costs.

"We have bill collectors knocking and banging on the door all the time," explains Ms Blaise.

As many as half of the city's bars and restaurants will go bust in the next six months as a result of the pandemic, according to New York state comptroller Thomas DiNapoli.

Despite the dire forecast, Mr Gentile has no plans to quit.

"This place used to be hopping," he says wistfully. "It can still be that way."

On 30 September, indoor dining returned to the city for the first time since the start of the pandemic at 25% capacity. But Mr Gentile says it's not enough.

The student

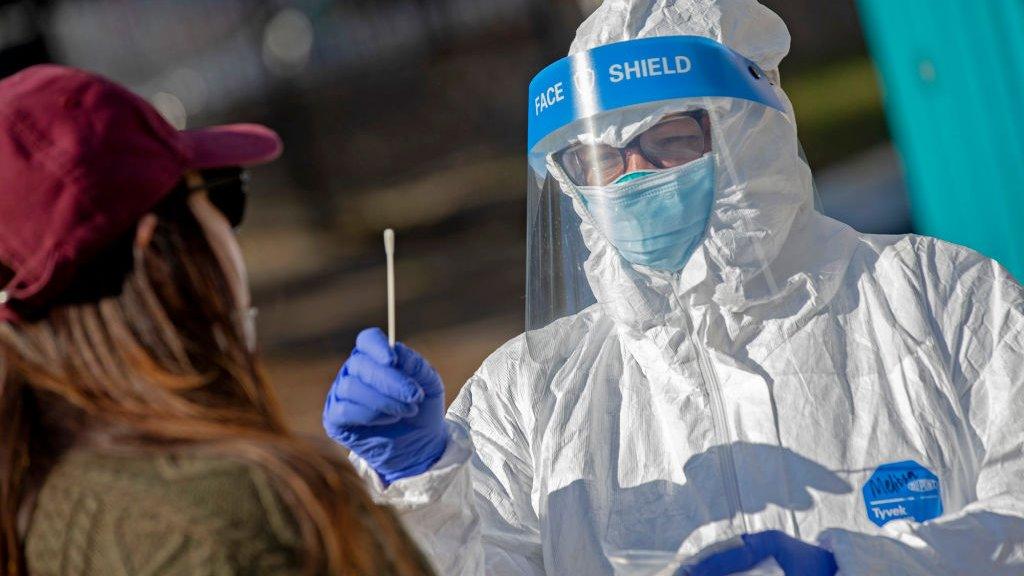

Andrew Sapini joined Bravo Volunteer Ambulance as an emergency medical technician

Away from the neighbourhood's busier blocks, Bay Ridge can feel distinctly suburban.

On one of its quieter residential streets, Andrew Sapini gets ready to go to work.

He joined Bravo Volunteer Ambulance as an emergency medical technician at a time when the city was facing a shortage of crew. At 21, he is one of its youngest members.

"It was pretty crazy and scary," he says reflecting on the early days of the virus, which has claimed more than 20,000 lives in the city.

As a third-year university student in Massachusetts, Mr Sapini shouldn't have been in Brooklyn at all. But when his college suspended classes in March, he moved back home with his parents in Bay Ridge. His courses moved online.

"We would hear on the news how things were getting worse," he remembers. "We thought it wouldn't really affect us that much."

Several months later, the virus has shifted the way he sees life after graduation. Serving as an EMT in New York City during the coronavirus pandemic has solidified his aim of going into medicine.

"I feel like I am prepared for this," Mr Sapini says.

This autumn, he has returned to college where he is helping to administer Covid tests.

The community organiser

During the pandemic, Mohamed Bahe turned his mosque into a food bank

With many in the area in desperate need, charities are under increased pressure.

Mohamed Bahe is the founder of the volunteer group Muslims Giving Back, which caters to the neighbourhood's Arab American community.

During the pandemic, he turned his mosque into a food bank helping working class immigrant families.

"Once the lockdown was announced, there was a surge," he says, of families coming to him for help. By May, 125 families were receiving food from the mosque.

Once a week Muslims Giving Back travels into Manhattan to feed the homeless late at night. While many New Yorkers sheltered in place to protect their health and limit the spread of the virus, Mr Bahe chats and jokes with those waiting for their food.

Mohamed Bahe is the founder of the volunteer group Muslims Giving Back

"We realized a lot of churches, places of worship that had soup kitchens closed," he explains.

As word spread that someone was giving out hot meals during the city's lockdown, the queue doubled overnight.

For Muslims Giving Back, the demand for help has slowed as restrictions in the city have eased. But there are still plenty in need.

Mr Bahe says he's more nervous about the economic crisis than the health crisis. He fears people who have lost their jobs will next lose their homes, and reliance on charity from the community will grow.

"For me, that's the true second wave that's coming."

- Published24 October 2020

- Published8 October 2020

- Published19 October 2020