'Working from home has made childcare easier'

- Published

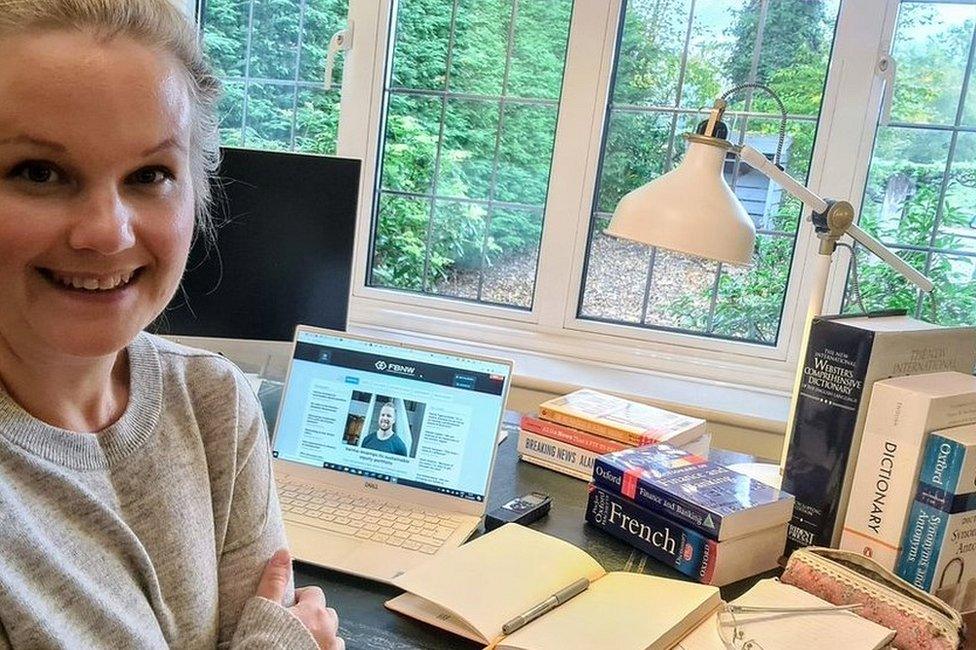

Rebecca Green, a mum of one, says working from home has made her work-life balance "manageable"

With a great many of us continuing to work from home, is it levelling the playing field for working mothers who previously had to put their children before their careers? Journalist Katherine Latham, herself a mum of three young kids, takes a closer look.

Something you don't learn at your antenatal classes is how hard it is to hold down a paid job and be a mum at the same time.

You aren't told that you will have to make a choice: to continue on your career path, earn a good living, and realise your ambitions - or prioritise caring for your children.

Studies show that it is a widespread issue. A government report last year found that almost a third of women in the UK with a child aged 14 or under had needed to cut their working hours because of childcare issues, external. For men it was just one in 10.

Many mothers are simply unable to juggle the nursery or school runs with long commutes and stressful jobs. So they end up either reducing their hours, quitting altogether, or getting a lower paid but more local job. Previous career goals seem suddenly unachievable.

But with the pandemic has come widespread home working. And it has become acceptable to do a video call with a toddler hanging around your neck or to adjust your hours to fit in with bath time.

Janina Johanna Sibelius says British husbands should do a fairer share of childcare and household chores

With many firms now realising their staff can successfully work remotely, and some even going as far as doing away with their offices altogether, external, could this be a chance for women to get back on the career ladder?

When civil servant Rebecca Green, 29, found out she was pregnant two years ago she thought she'd have to reduce her hours - losing income and seriously affecting her career prospects.

With her husband away in the Royal Navy for months at a time, it was going to be left to her to juggle childcare, commuting and working long hours. It promised to be stressful and tiring, and she would barely see her young daughter midweek.

Then the lockdown arrived while Ms Green was on still on maternity leave. When she did return to work in the summer, it was from her home in Monmouthshire.

Without a lengthy commute, she could enjoy breakfast with her daughter Bethan, and then finish work in time for tea.

"It would have been difficult to fit getting Bethan to nursery and me to work, on time," says Ms Green. "Working from home has made it easier for sure.

"It is much more manageable now. It wouldn't have been sustainable before."

Janina Johanna Sibelius, a mother of two children, aged nine and 11 agrees that working from home has made her life easier.

"My company is very understanding," says the 40-year-old, who lives in London, and works in publishing. "As long as I get the job done there is no pressure to waste hours in front of a screen just so that you can say you worked certain hours.

"There is no point doing that when you work in a team of professionals who know how to do their jobs. There is trust that everyone will do what needs to be done to achieve the common goals."

Kara Gammell says coronavirus "has levelled the playing field for women in my profession"

However, working from home is not without its challenges. In many cases women are still having to shoulder the largest share of household chores and childcare - despite husbands also now working from the kitchen table or study.

During the UK-wide lockdown earlier this year, mothers spent an average of three hours and 32 minutes on such unpaid labour per day, external, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The average daily time for fathers was two hours and 25 minutes, more than an hour less, says the ONS.

Ms Sibelius and her husband are originally from Finland, where it is commonplace for parents to share household chores and childcare evenly. She says that the cultural expectations of UK men and women need to change.

Kara Gammell says she can do breakfast radio interviews while her daughter is still in bed

"British society sees it as a mother's job to handle the children's day-to-day activities while fathers are expected to work a full day without interruption," she says.

"It is seen as a sin for a father to come in late after dropping his kids off at school. This is absolutely appalling. How are we ever going to achieve equality between men and women if men are actively encouraged not to participate in family life?"

Working Families, a UK charity campaigning for a better work-life balance, said in a report last month that "many parents felt their employer's cultural resistance to working remotely had been broken down by the pandemic", external.

The charity says it also found that firms reported staff productivity "had been the same or better than usual during lockdown", external. It puts this down to factors such as employees being pleased that they are trusted to work remotely, the end of "presenteeism", the removal of commuting and more flexible working hours.

Meanwhile, half of business leaders would now be more likely to consider hiring someone who was not within commuting distance, external, according to a poll by the magazine and website Management Today.

Rebecca Green is home alone with her daughter for months on end as her husband is in the Royal Navy

Kara Gammell, a financial journalist and founder of the blog Your Best Friend's Guide To Cash, says that coronavirus "has levelled the playing field for women in my profession".

"Now, it is standard that all television and radio guest slots are done remotely," adds the 41-year-old single mother. "I can appear on the radio before my daughter even wakes up - and I can still do the school run.

"One of the few positives of the pandemic is that employers have been forced to embrace flexible working. People with childcare responsibilities no longer feel it is a case of 'either/or'.

New Economy is a new series exploring how businesses, trade, economies and working life are changing fast.

"The 'bums on seats' mentality may be gone for good and, for me, that is a complete game changer. I am busier than ever because of the change in attitude to working remotely."

Jane van Zyl, chief executive of Working Families, says she hopes that working from home is here stay for people who want it, and that it will enable more women to stay in their jobs and careers of choice after having children.

"An estimated 54,000 women [in the UK] lose their jobs every year, simply because they have had a baby," she says. "This motherhood penalty is a key driver for the UK's persistent gender pay gap."