What will happen to closed High Street shops?

- Published

- comments

The collapse of the Debenhams and Arcadia retail empires is likely to leave large gaps in High Streets and shopping centres up and down the UK.

If history is a guide, it may be years until some of these shops reopen, while many never will.

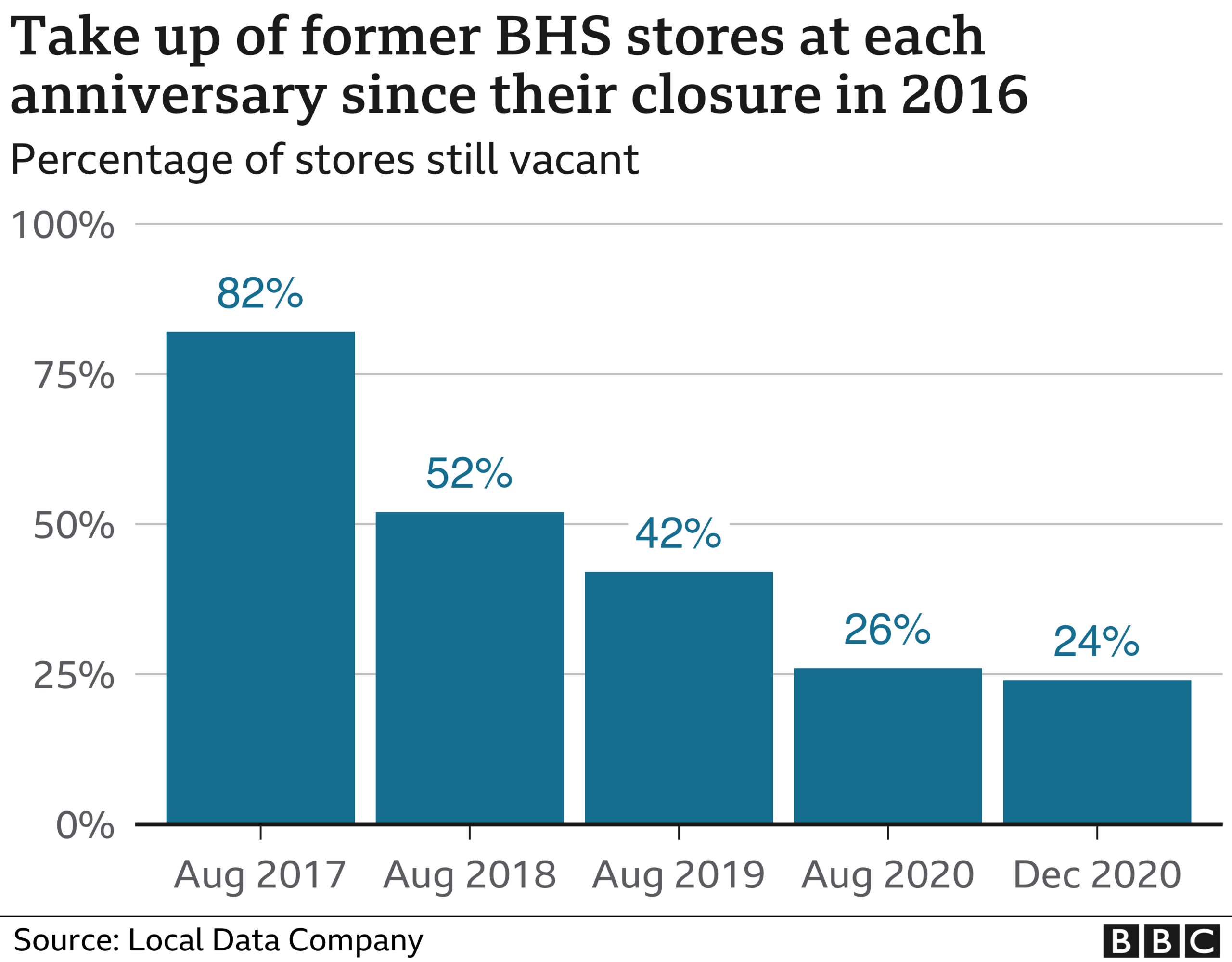

It is now more than four years since the closure of BHS, the last large department store chain to be wiped from the High Street.

Yet 24% of its stores still lie empty.

Those premises that have been put to use have been snapped up by expanding brands such as Primark, B&M Bargains, H&M and Sports Direct, says Ronald Nyakairu, senior manager at the Local Data Company (LDC)

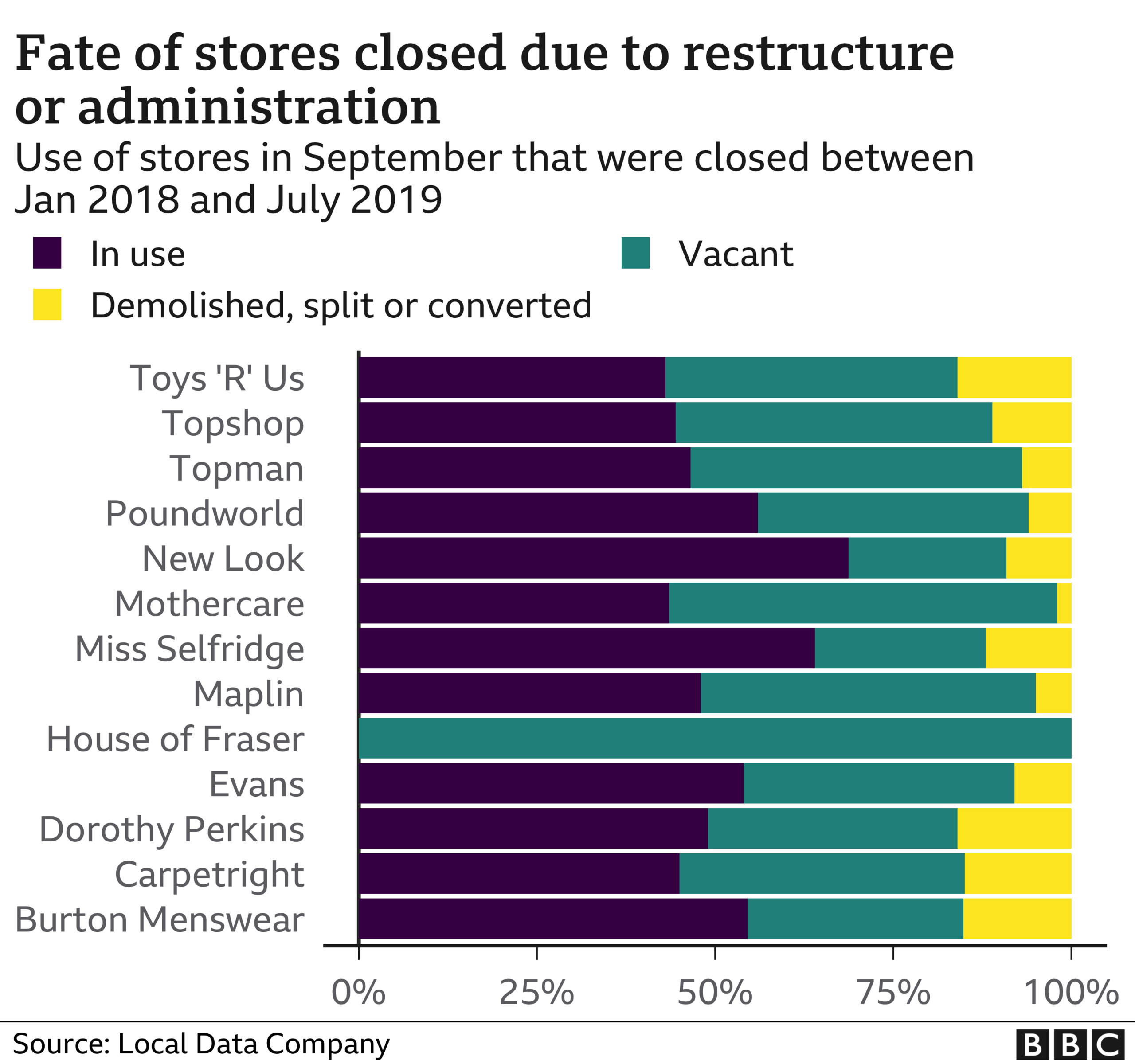

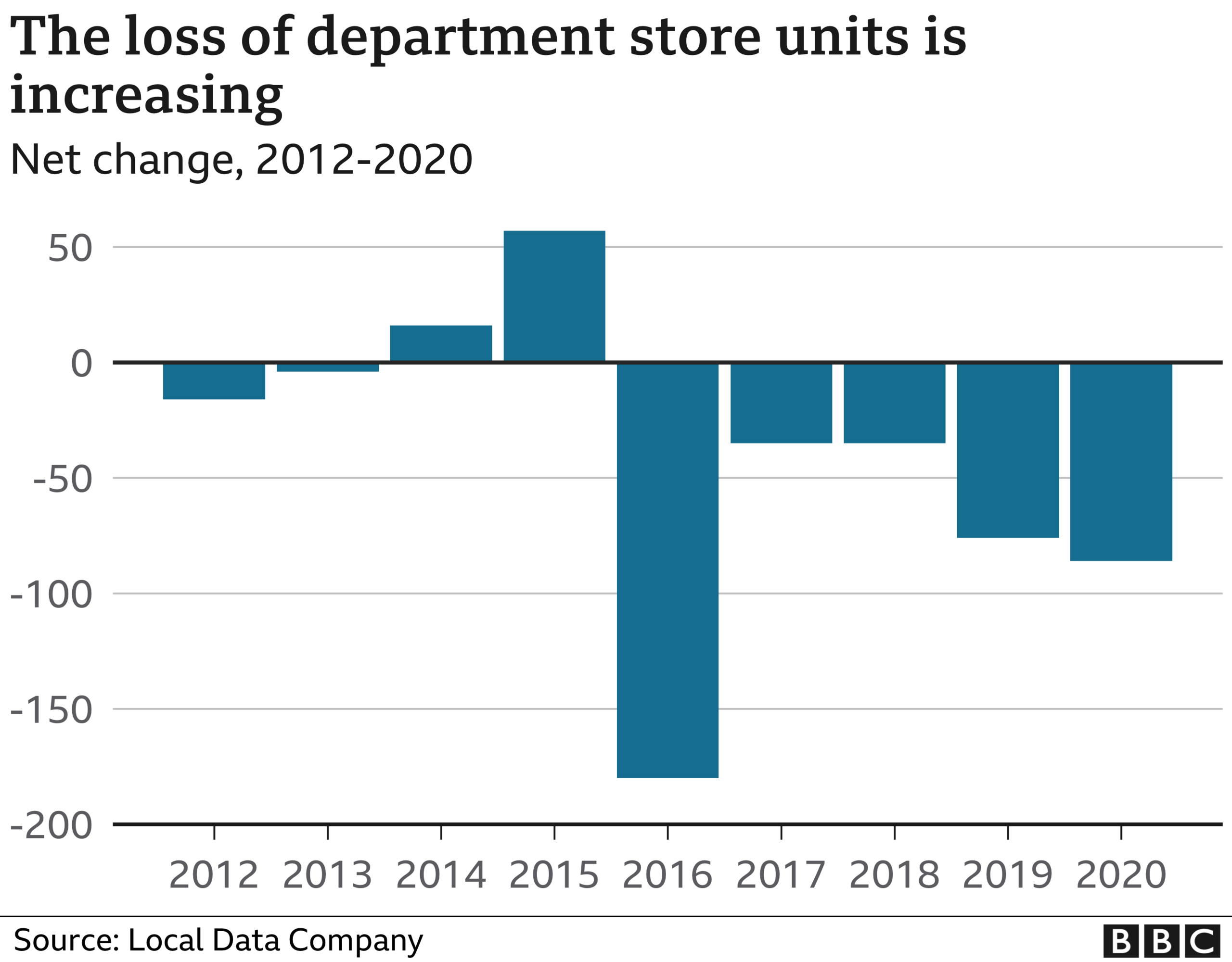

But even among smaller stores which closed their doors amid the slow decline of bricks-and-mortar retailers before coronavirus, many are vacant or have been demolished or converted, according to LDC data.

Its analysis suggests that bigger premises, such as those formerly occupied by Toys 'R' Us or House of Fraser, have been harder to re-let.

This probably spells a permanent change that landlords and local authorities need to get used to and even seize, says Bill Grimsey, former head of Wickes, Iceland and Focus DIY. He has led three reports into the future of town centres and High Streets.

"You can't rely on retail any more for your town centres and High Streets as the main attraction, because of technology, because of the internet," he says.

"You need to reinvent these places for something else because we are social animals and we need to have a place to congregate and it won't be just shops."

He concedes that managers of his generation were "part of the cohort than cloned every town centre" with the same shop chains, and that a return to vibrant towns with individual attractions is needed.

He envisages a mix of health, education, entertainment, leisure, arts and crafts and green spaces. Some old shops could become housing, he adds.

He urges local authorities to take a lead, even through means such as compulsory purchase to stop empty buildings going to waste.

"It's a big change that's needed and that requires local leaders to find the owners and start to recognise that repurposing them is the way forward."

Cities that have suffered less during the High Street recession are those such as Brighton, Manchester and Leeds that have relied less on shops, says Paul Swinney, director of policy and research at the Centre for Cities.

These centres have more office space and higher-paid workers, who have then propped up bars, restaurants and shops after work.

For department stores in popular areas, there are ways to cope with fewer sales in-store, he says, pointing to John Lewis's application to convert part of its flagship London store to office space, external.

But he cautions that for smaller towns whose custom may be dwindling, that will not be an option, and stronger medicine will be needed.

Many BHS stores, like this one in Bolton, remain closed

While Mr Grimsey recommends that local authorities take the reins, he sees more of a role for central government, which has the financial muscle to buy struggling units and turn them into something vibrant, later selling them on.

"Having that control of the building rather than it being passed off to a group of investors that aren't linked to the place is probably a thing the government can do," he says.

"This grave situation presents an opportunity to take control of these things. There's an opportunity to get a good deal, do something with them and then sell them down the line."

Mark Robinson, who co-founded landlord Ellandi and heads the government-commissioned High Streets Task Force, also points to "monoculture" in town centres as something that must change.

Ellandi owns 33 shopping centres around the UK.

"Landlords I know realise we have to be flexible, encourage vibrancy, not just the highest rent," he says.

"We need to be flexible about who we bring in and the terms. We are not going to get 20-year leases any more."

It will mean, at least in the short term, some pain for landlords' bottom line, Mr Robinson says.

"Rents are going to fall and they have fallen considerably. Might that encourage more entrepreneurialism? Yes. Might it encourage independent retailers in far more prominent locations? Absolutely. Does it mean taking risks? Absolutely. And this has to be good for the future."

He says that reform will be over when the presence or absence of a particular brand or shop on the High Street is no longer the measure for a town's success.

"We created 400 clone towns nobody loves. We shouldn't get upset - job losses aside - about changing them."

Related topics

- Published4 July 2018

- Published30 August 2020