Covid vaccines: Will drug companies make bumper profits?

- Published

At the start of the pandemic, we were warned: it takes years to develop a vaccine, so don't expect too much too soon.

Now, after only 10 months, the injections have begun and the firms behind the front-runners are household names.

As a result, investment analysts are forecasting that at least two of them, American biotech company Moderna and Germany's BioNTech with its partner, US giant Pfizer, would be likely to make billions of dollars next year.

But it's not clear how much vaccine makers really are set to cash in beyond that.

Thanks to the way these vaccines have been funded and the number of firms joining the race to make them, any opportunity to make big profits could be short-lived.

Who put the money in?

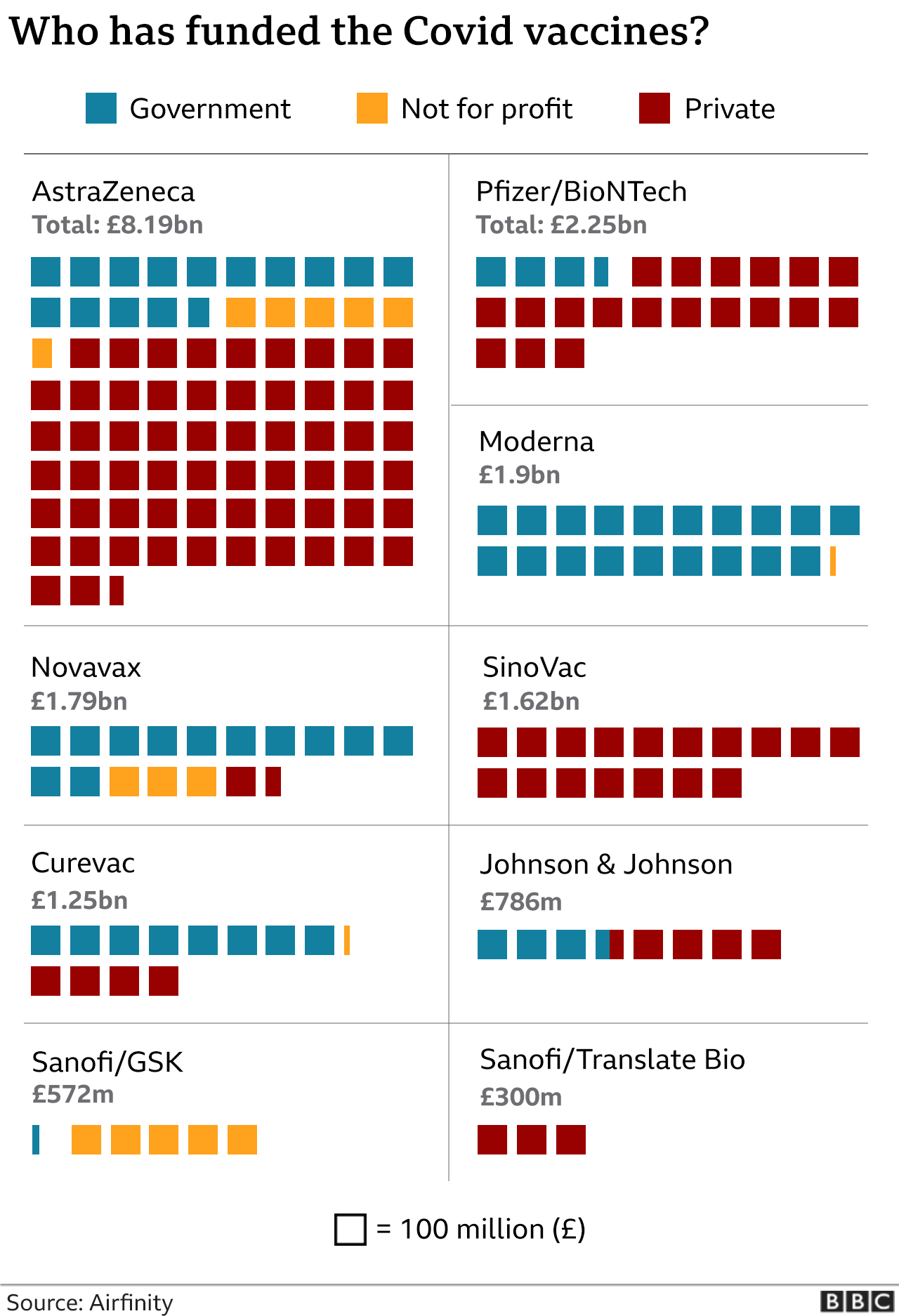

Due to the urgent need for the vaccine, governments and donors, have poured billions of pounds into projects to create and test them. Philanthropic organisations such as the Gates Foundation backed the quest as well as individuals including Alibaba founder Jack Ma and country music star Dolly Parton.

In total, governments have provided £6.5bn, according to science data analytics company Airfinity. Not-for-profit organisations have provided nearly £1.5bn.

The graphic above has been updated since this article was first published. As it suggests, in total private companies have invested billions of pounds into vaccine development.

However, initially firms didn't rush in to fund vaccine projects. Creating vaccines, especially in the teeth of an acute health emergency, hasn't proved very profitable in the past. The discovery process takes time and is far from certain. Poorer nations need large supplies but can't afford high prices. And vaccines usually need to be administered just once or twice. Medications that are wanted in wealthier countries, especially ones that require daily doses, are bigger money-spinners.

Firms that began work on vaccines for other diseases such as Zika and Sars had their fingers burnt. On the other hand, the market for flu' jabs, which is worth several billion dollars a year, suggests that if Covid-19, like flu, is here to stay and requires annual booster jabs, then it could be profitable for the firms that come up with the most effective, and most cost-effective products.

What are they charging?

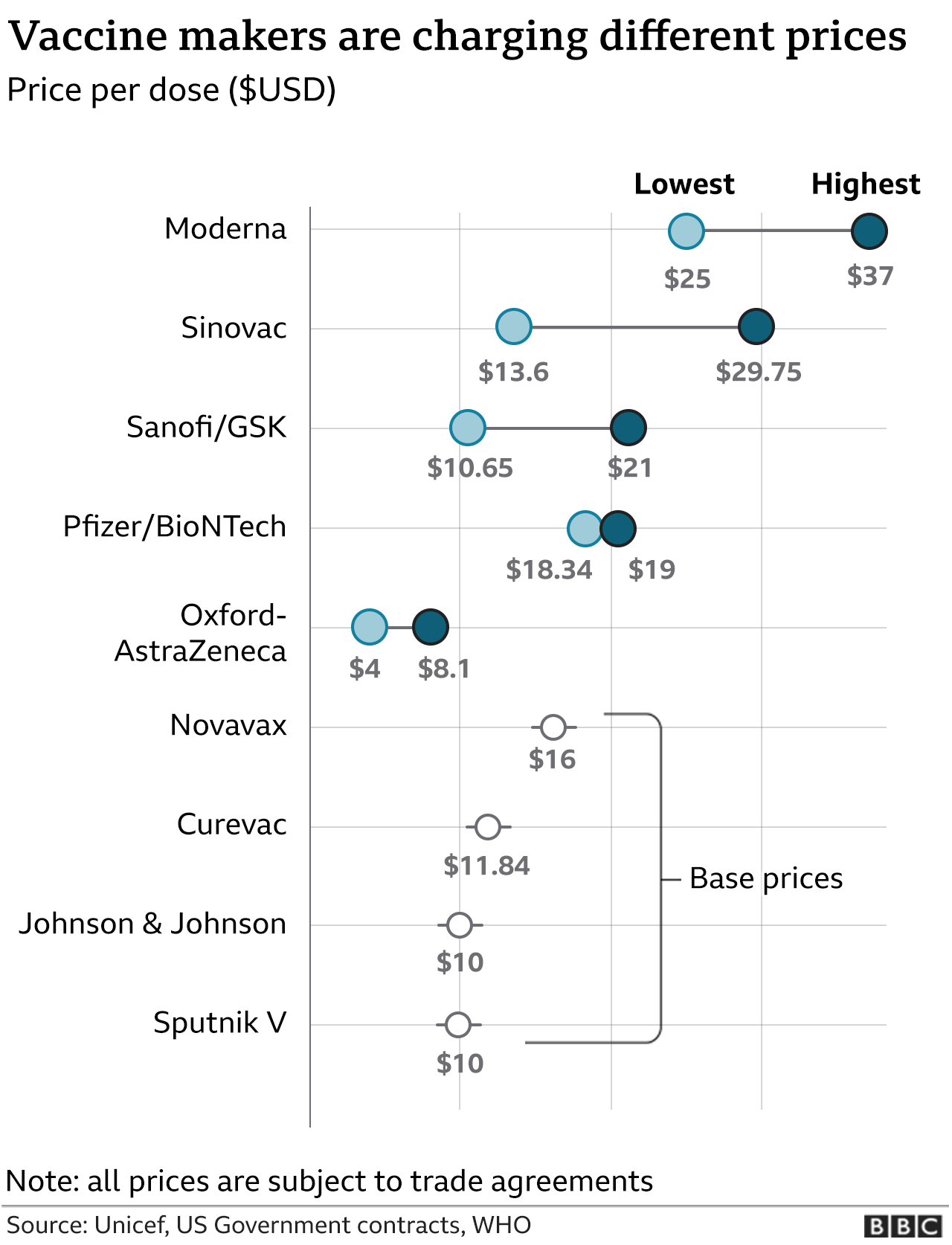

Some firms don't want to be seen to be profiting from the global crisis, especially after receiving so much outside funding. The large US drugmaker, Johnson & Johnson, and the UK's AstraZeneca, which is working with a University of Oxford-based biotech company, have pledged to sell the vaccine at a price that just covers their costs. AstraZeneca's currently looks set to be the cheapest at $4 (£3) per dose.

Moderna, a small biotechnology firm, which has been working on the technology behind its ground-breaking RNA vaccine for years, is pricing theirs much higher, at up to $37 per dose. Its aim is to make some profit for the firms' shareholders (although part of the higher price will also cover the costs of transporting those vaccines at very low temperatures).

That doesn't mean those prices are fixed, though.

Typically, pharmaceutical companies charge different amounts in different countries, according to what governments can afford.

AstraZeneca's promise to keep prices low extends only for the "duration of the pandemic". It could start charging higher prices as early as next year, depending on the path of the disease.

"Right now, governments in the rich world will pay high prices, they are so eager to get their hands on anything that can help bring an end to the pandemic," says Emily Field, head of European pharmaceutical research at Barclays.

As soon as more vaccines come on stream, probably next year, competition may well push prices lower, she says.

Pfizer hasn't taken any outside funding, but its partner BioNTech has been backed by the German government

In the meantime, we shouldn't expect private firms - especially the smaller ones with no other products to sell - to make vaccines without looking for any profit, argues Rasmus Bech Hansen, chief executive of Airfinity.

"Bear in mind these companies took a significant risk, moved really fast, and the research and development investments have been significant," he says.

And if you want small firms to keep making breakthroughs in future, he says, you need to reward them.

But some argue the sheer scale of the humanitarian crisis, and the public financing, means it isn't a time for business as usual.

Should they be sharing their technology?

With so much at stake, there have been calls for the know-how behind the new vaccines to be pooled, so that other firms in India and South Africa, for example, can manufacture doses for their own markets.

Ellen 't Hoen, director of research group Medicines Law and Policy, says that should have been a condition of receiving public funding.

"I think it was unwise of our governments to hand over that money without strings attached," she says.

At the start of the pandemic, she says, big pharmaceutical companies showed little interest in the race for a vaccine. Only when governments and agencies stepped in with funding pledges did they get to work on it. So she doesn't see why they should have exclusive rights to profit from the results.

"These innovations become the private property of these commercial organisations and the control over who gets access to the innovation and access to the knowledge of how to make them stays in the hands of the company," she says.

While there is some sharing of intellectual property going on, she says it's nowhere near enough.

So will pharma companies make bumper profits?

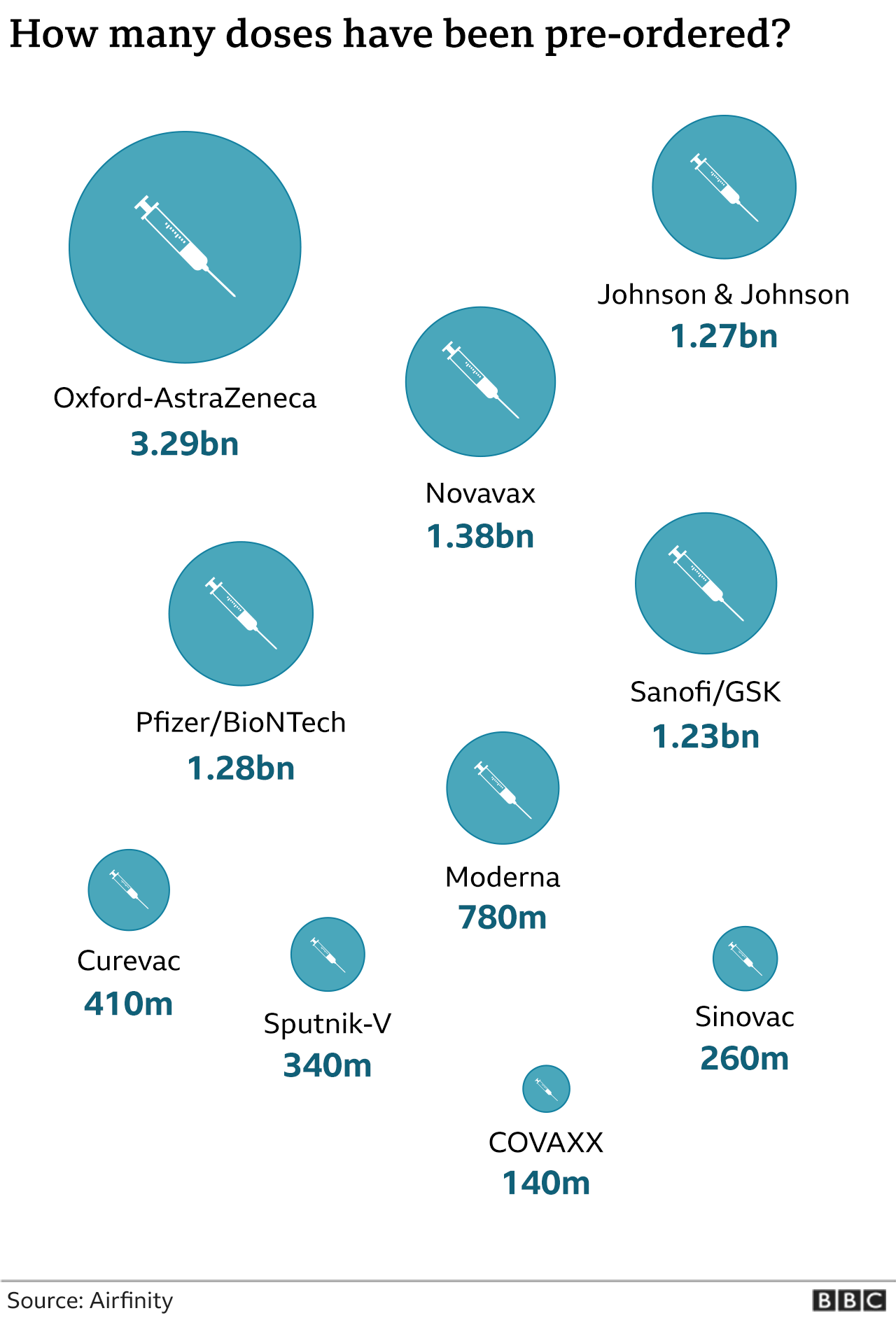

Governments and multilateral organisations have already pledged to buy billions of doses at set prices. So for the next few months, firms will be busy fulfilling those orders as quickly as possible.

Those that are selling to countries with deeper pockets will start to see a return on their investment, whereas AstraZeneca, despite having deals to supply the highest number of doses, will only cover its costs.

After those first contracts have been fulfilled, it is harder to predict what the new vaccine landscape will look like.

It depends on many things: how long immunity lasts in those vaccinated, how many successful vaccines come on stream and whether production and distribution is going smoothly.

Barclays' Emily Field thinks the window to make profits will be "very temporary".

Even if the front-runners don't share their intellectual property, there are already more than 50 vaccines in clinical trials around the world.

"In two years' time, there could be 20 vaccines on the market," says Ms Field. "It's going to be difficult to charge a premium price."

She thinks the impact in the long run will have more to do with reputation. A successful vaccine roll-out could help open doors for selling Covid therapies or other products.

In that respect, the whole industry is set to benefit, agrees Airfinity's Rasmus Bech Hansen.

In future, governments may spend more on pandemic preparedness

"That's one of the silver linings that could come out of the pandemic," he says.

In future, he expects governments to invest in pandemic strategies the way they do now in defence, viewing it as a necessary expenditure on things they hope not to use.

Most promising of all, and one reason why the market value of BioNTech and Moderna has soared, is that their vaccines provide a proof of concept for their RNA technology.

"Everyone was impressed with its effectiveness," says Emily Field. "It could change the landscape for vaccines."

Before Covid, BioNTech was working on a vaccine for skin cancer. Moderna is pursuing an RNA-based vaccine for ovarian cancer.

If either of those succeeds, then the rewards could be huge.

- Published18 November 2020

- Published8 December 2020

- Published8 December 2020

- Published28 May 2021

- Published20 January 2021