Could Brexit make my food more expensive?

- Published

On 1 January, Britain will stop following EU rules, and we'll have a new trade relationship with Europe.

We don't yet know what that relationship will be, but the effect will be felt by everyone - in their shopping basket.

Why will Brexit affect the food I buy?

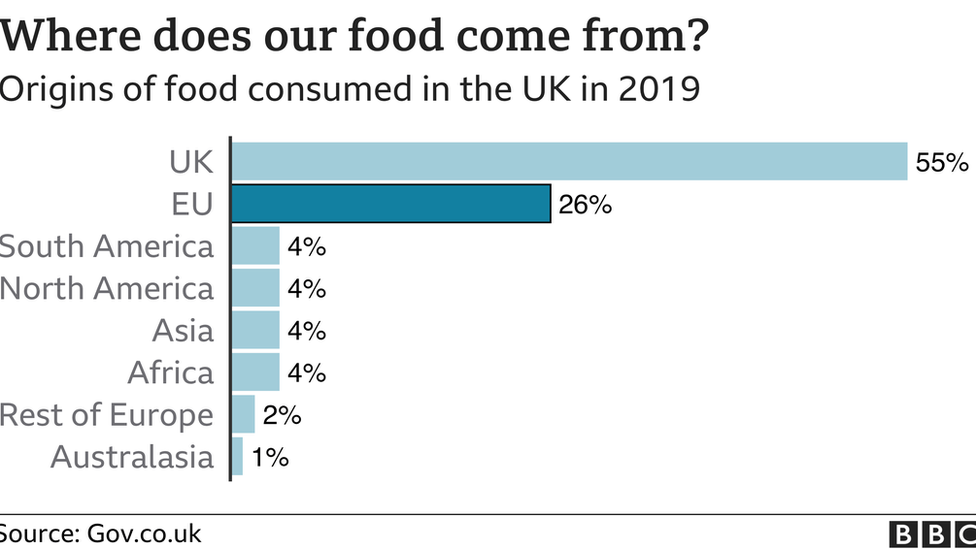

Just over a quarter of all food eaten in the UK is produced in the EU.

Even though the UK left the EU on 31 January this year, trading with the EU carried on as it did before. Spanish lettuce, Dutch tomatoes, French wine and Danish bacon came into the UK without checks on the border, and without the UK government applying any import taxes - known as tariffs.

After 1 January, the rules change but agreement is still being negotiated, but there are two main possible outcomes.

The UK and the EU may agree a new trade deal, which allows those imports to continue without tariffs being paid.

Or, if the UK and the EU can't agree a deal, trade between the countries must follow to the rules set out by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) which include significant tariffs on foods heading in directions.

Will food be more expensive after 1 January?

Under WTO rules, supermarkets and other importers would have to pay substantial tariffs on many foods they bring in from the EU.

Meat and dairy products face particularly high tariffs, but many other areas including fruit and vegetables would be also affected.

As an extreme case, the London School of Economics estimates that some speciality cheeses such as halloumi and roquefort could be 55% more expensive.

(Tariffs don't just apply to food - cars made in the EU, for instance, would attract a 10% tariff. But food and drinks are the area where the highest tariffs apply.)

Government minister George Eustice said prices on average would rise less than 2% due to tariffs, although he admitted some items such as pork and beef would be hit harder.

Tesco has said prices could rise between 3% to 5% on average but "vastly more on some selected items" such as imported brie cheese.

In the short term, shops could absorb those extra costs themselves. But in the longer term they would likely pass some or all of that cost on to customers, in the form of higher prices.

French camembert and brie would be more expensive in the event of a no-deal Brexit

Tariffs aren't the only reason why prices could rise.

Retailers will have to fill in more paperwork when they bring food in and out of the UK, and producers could have to comply with different regulations on different sides of the channel. All of which costs money.

That means that even if there is a deal which reduces all tariffs on imports from the EU to zero, prices could still rise.

Adding all those costs up, the London School of Economics estimated that a trade deal would see an average price rise of 4.7% for unbranded food products imported from the EU. Without a deal they would rise by 12.5%.

Could there be food shortages?

A no-deal scenario would mean significant extra paperwork and checks on goods entering the UK, which could delay some deliveries of food from the EU.

Some British ports are already seeing delays in getting shipments through, with increased traffic partly caused by importers rushing to beat the 1 January deadline.

Many retailers including Tesco have been stockpiling goods in preparation for some disruption.

Retailers are increasing their stocks of tins, toilet rolls and other longer life products, the British Retail Consortium (BRC) which speaks for the supermarkets and other shops, says.

It specifically warned people not to stockpile food at home, saying there will be sufficient supply of essential products.

But perishable items cannot be stockpiled, and some could be in short supply in the early months of next year.

The BRC says that lettuce, strawberries, raspberries and cut flowers are the most vulnerable to delays in shipping, but it doesn't expect these goods to be unavailable.

Couldn't we just produce more food in the UK?

More than half of all food consumed in the UK is currently produced in the UK. That proportion could be increased, but there are issues.

Some food is just easier and cheaper to produce in sunnier places, especially when it's out of season in the UK. The UK could seek new suppliers for those products outside the EU, buying from Morocco instead of from Greece or Italy, for instance. But those imports may also be subject to tariffs, and longer distances would mean higher transport costs.

In any case, it would take time for supermarkets to find new suppliers, whether at home or abroad, so there could be a delay.

UK meat producers also say that if tariffs made it impossible to export animal parts which are difficult to sell in the UK, such as pigs' trotters, they would have to charge UK consumers more to make up for the loss.

Farming and food processing also currently employ large numbers of migrants from the EU, who will find it harder to enter the UK next year when the new rules come into force. This could make it more difficult to scale up food production.

Many UK growers depend on seasonal migrant workers from Eastern Europe

Could some food get cheaper?

Leaving the EU means the UK has the freedom to agree new trade deals with non-EU countries, which could bring down tariffs and give British shoppers access to cheaper food from countries like the US or Brazil. However, trade deals take a long time to negotiate.

The UK can cut tariffs without doing trade deals, but WTO rules say it has to offer the same terms to every country that doesn't have a trade deal. So it could cut tariffs on EU imports to zero, as long as it cut tariffs to zero across the board.

That would make many foods cheaper, but it would be devastating for many UK farmers who would struggle to compete with cheap imports.