Brexit: 'Putting UK, not GB, delayed my fish for 24 hours'

- Published

Graham Flannigan and his daughter Emma currently have a backlog of crabs and lobsters

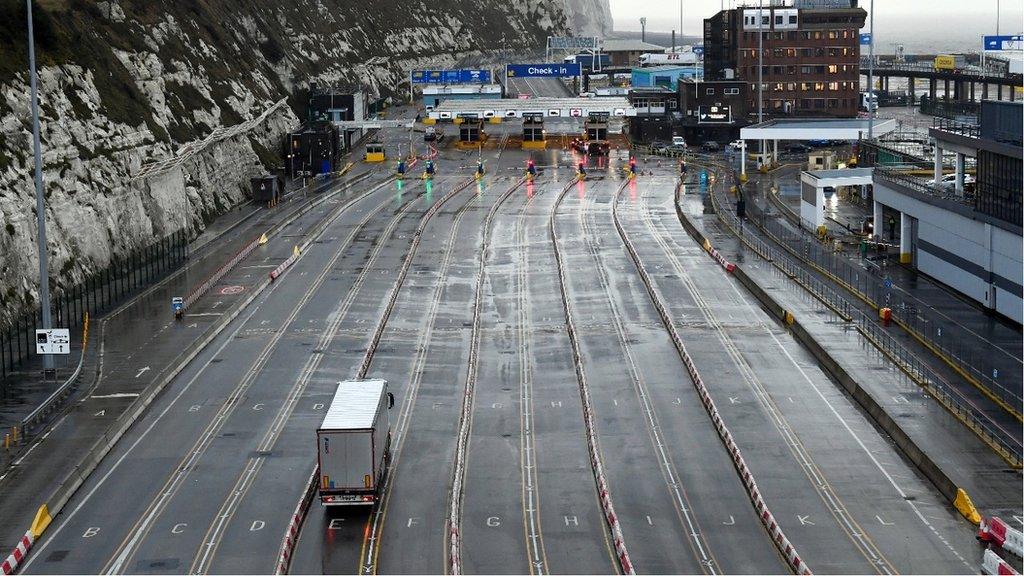

Two weeks into the UK's new trading relationship with the EU, there appear to be teething troubles.

Logistics firms have paused deliveries to the UK. Exporters point to huge increases in documentation required. And firms dealing with perishable produce say they have lost money over delays at border crossings.

Some of these hurdles are likely to be overcome as the new rules bed in. Others may prove to be more persistent.

To find out the current state of play, we spoke to four firms in different sectors.

'We've gone back 30 years'

Berwick Shellfish is getting calls from its customers in France "desperate" for deliveries, says boss Graham Flannigan.

When he looks out of his window, he can see a fishing boat off the coast. The fisherman texts daily to ask if he can land his catch.

But Mr Flannigan texts back "no". His tanks are already full of crabs and lobster that he can't get to customers.

"Logistics have ground to a halt," he says. "Every shipment has to have four sheets of paper to accompany the goods. Before 31 December, we had one piece of paper, a despatch note."

Last year, 87% of Berwick Shellfish's £1.7m sales went to France, Spain and Germany. Now a lot has been put on hold.

Mr Flannigan managed to get a shipment of periwinkles through to La Rochelle on France's west coast, although there was a 24 hour hold-up because he'd put "UK" on a label and the vet examining it in Glasgow said it had to say "GB".

Eventually a new label was attached to the outside of the pallets with adhesive tape.

But a regular order from Barcelona for crabs and lobsters that are usually transported live in oxygenated salt water tanks has been postponed until February, in the hope things will be running more smoothly by then.

"When we had a [Brexit] deal, I thought, we're saved all the rigmarole and hassle, it'll work sweet as a nut, but it hasn't happened," says Mr Flannigan. Instead, he says, it feels like the clock's been turned back 30 years.

'The real test is the next two to three weeks'

Rob Munro, managing director of Carr's Flour Mills thinks things will "get worse before it gets better"

"There's a noticeable regulatory burden that wasn't there before and it's fair to say goods are moving more slowly," admits Rob Munro, managing director of Carr's Flour Mills.

"We're all learning what the new systems are. There's an element of error, but we're learning very quickly."

Carr's takes UK and imported wheat and mills it, selling to individuals and business customers. They've been flat out since the first lockdown prompted Britons to take up baking in droves.

But by the end of the year, they had also stockpiled enough wheat to see them through a worst-case scenario, no-deal Brexit. So had many of their customers. As a result, the start of January was relatively quiet for them.

"The real test for me is the next two to three weeks, as inventory is depleted and orders increase," says Mr Munro.

He thinks there is a window of opportunity now, for the authorities to fine tune the system before volumes are ramped up.

Some of his customers in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland have been caught out by rule changes that mean they now have to pay tariffs on some products, if they contain wheat imported from outside the UK and the EU.

There are ways round that, he says, such as reformulating flour mixes. But the Brexit deal was so last-minute, there hasn't been time.

"The government is suggesting it'll get worse before it gets better," he says. "I think that's probably true."

'Our challenge is to work out what we'll be charged'

Newquay-based clothing retailer Celtic & Co has had to put up prices for European customers due to extra costs because of Brexit

Even with the prospect of Brexit on the horizon last year, clothing firm Celtic & Co decided to have its website translated into German and focus more of its marketing in the EU.

It paid off and, thanks in part to lockdown, sales of its Ugg-style boots, sheepskin slippers and chunky knits soared.

"Anything cosy that people want to be in at home has been really popular. Germany in particular has been a growing market," says Zoe Bray, Celtic & Co's head of sales and marketing.

The Newquay-based company is still optimistic about future sales growth in the EU. But it has already put up prices on its German site by 10-15%, prompting some disappointment among customers there.

"We're being told by the international courier we use that there are going to be extra costs and tariffs," says Ms Bray.

It's still far from clear what those will amount to.

The lack of clarity, says Ms Bray, means they are making decisions somewhat in the dark.

'We'd be screaming if we had a project in January'

Rosh Engineering boss Ian Dormer isn't sure yet how Brexit will affect servicing contracts with customers in Europe

Ian Dormer, boss of Newcastle-based firm Rosh Engineering, says that after years of Brexit uncertainty, he feels like a man who has taken his hand out of a vice.

"You're absolutely relieved you've got it out, but why heck did we put it in in the first place?" he says. "You have to check your fingers still work."

The first real test came this week when a component was delivered from France, only slightly behind schedule.

"A day [delay] you can live with," he says. "The borders are working OK as far as I can see."

But while Rosh Engineering does import and install high-voltage power transformers in the UK, the lion's share of its business is in servicing existing projects, many of which are abroad.

Because of Covid, they don't have any imminent projects, which is just as well, he says: "We'd be screaming if we had a contract in January or February."

However, an Italian company has hired Rosh for a project in Germany in April.

Mr Dormer has been scouring UK and German government websites for information. But he still doesn't know what will be required in terms of visas or whether his engineers' professional qualifications will be accepted.

He fears the "massive amount of aggravation" could mean business partners on the continent start to look elsewhere.

"The harder it becomes, the more expensive it is, the higher the chance we're not going to do it," he points out.

Related topics

- Published14 January 2021

- Published8 January 2021

- Published7 January 2021