UK borrowing hits highest December level on record

- Published

- comments

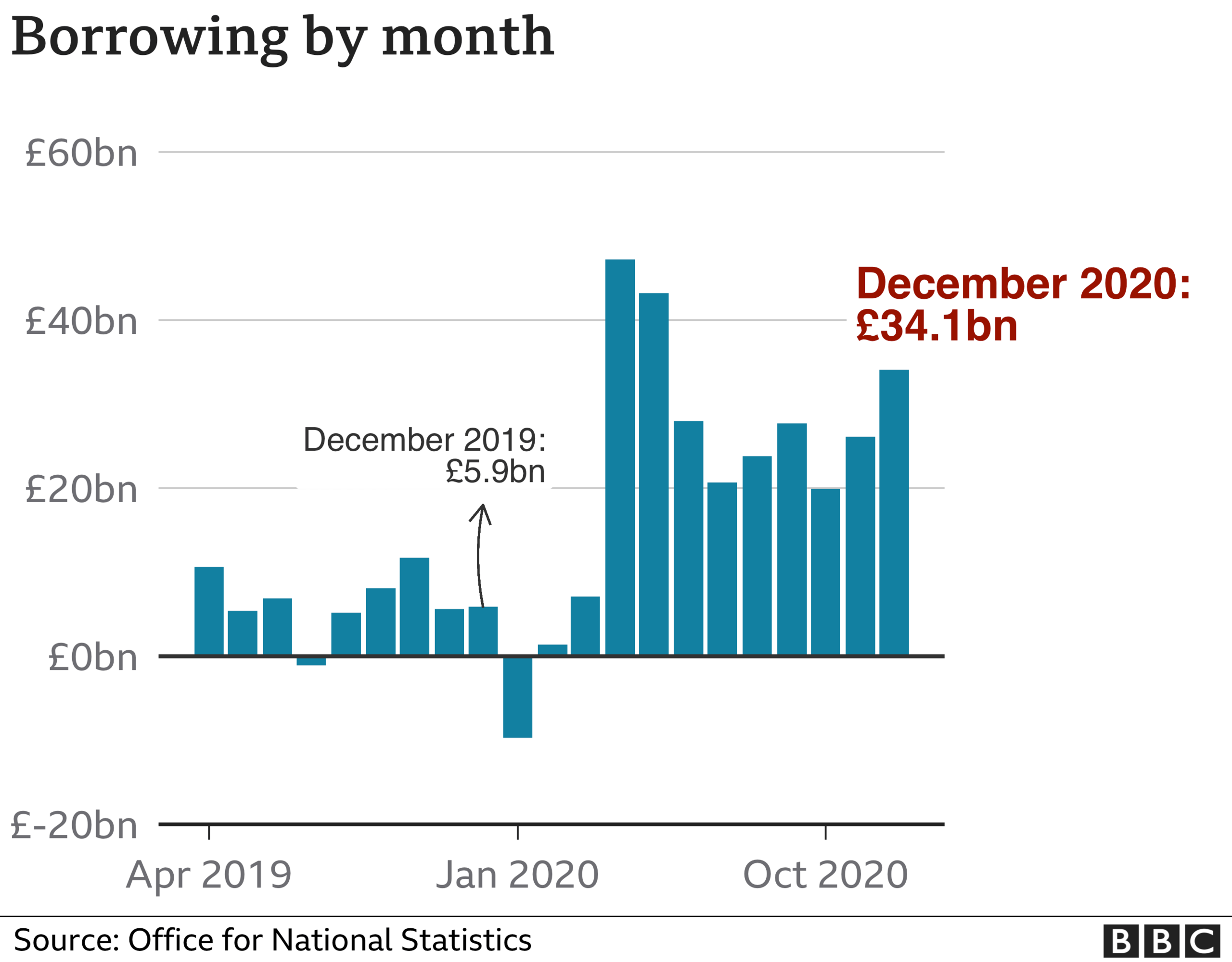

UK government borrowing hit £34.1bn last month, the highest December figure on record, as the cost of pandemic support weighed on the economy.

It was also the third-highest borrowing figure in any month since records began in 1993, the Office for National Statistics said., external

The figures underline Chancellor Rishi Sunak's problems as he prepares his March Budget.

Separately, a survey suggested activity at UK firms fell sharply this month.

The closely-watched Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI) from IHS Markit/CIPS, external found a "steep slump in business activity" during in January as lockdown measures continued, and warned that "a double-dip recession is on the cards".

Borrowing surge

Government borrowing for this financial year has now reached £270.8bn, which is £212.7bn more than a year ago, the ONS said.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has estimated that borrowing could reach £393.5bn by the end of the financial year in March.

A Budget had been expected to take place in autumn last year, but it was delayed because of the pandemic and will now take place on 3 March.

Mr Sunak has already imposed a pay freeze on at least 1.3 million public sector workers as part of efforts to contain government spending.

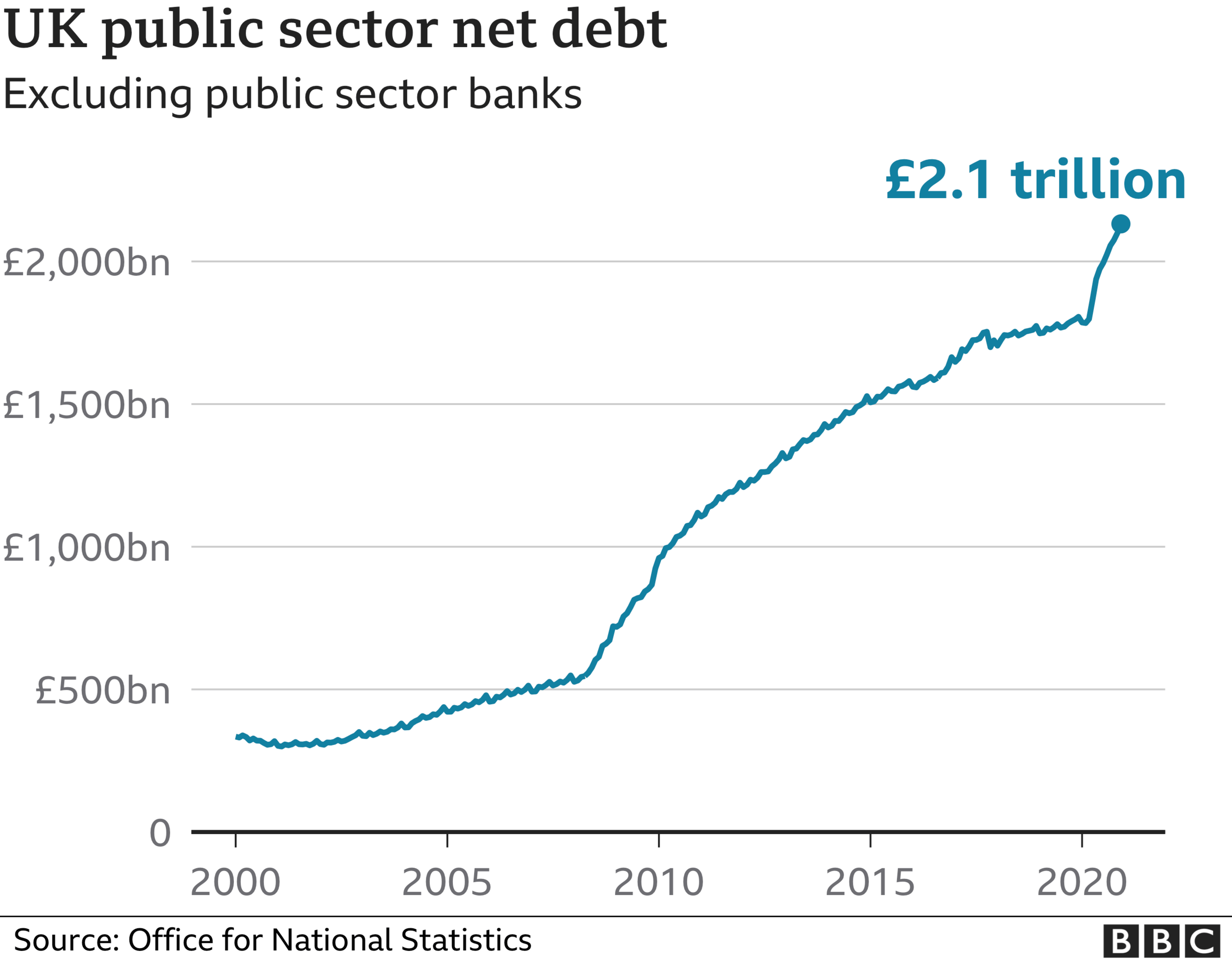

The increase in borrowing has led to a steep increase in the national debt, which now stands at £2.13 trillion.

The UK's overall debt has now reached 99.4% of gross domestic product (GDP) - a level not seen since the early 1960s.

Borrowing so far this financial year is at its highest level since monthly records began in 1993. The overall government deficit is still heading to its highest in peacetime. Having started to recover in late summer, the renewed shutdowns have again hit the numbers.

The actual amount of borrowing in December, at £34.1bn, was five times last year's amount and exceeded in only two previous months at the start of the pandemic lockdowns. Spending on jobs support, including the furlough scheme, was £10bn in the month alone.

Purchases of vaccines, testing equipment and PPE also pushed up borrowing by £9bn. Receipts of income tax, VAT and business rates were all around £1bn less than last December.

Despite the national debt now rising to just under 100% - the highest since the early 1960s - the interest paid on that debt was just £100m up on last December.

The chancellor said the figures showed it had been fiscally responsible to inject massive sums to support lives and livelihoods, but reiterated a message that he would look to return the public finances to a more sustainable footing when the recovery returns. The Budget in March will mark only a tentative start to this process.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said the latest borrowing figures, coupled with weak retail sales data, meant that the economy still needed the government's financial support.

"The chancellor should ensure that is the main focus of his Budget on 3 March and not a desire to reduce the budget deficit by raising taxes," he added.

In his reaction to the figures, Mr Sunak appeared to acknowledge that now was not the time for tax increases.

"Since the start of the pandemic we've invested over £280bn to protect jobs and livelihoods across the UK and support our economy and public services," he said.

"This has clearly been the fiscally responsible thing to do. But as I've said before, once our economy begins to recover, we should look to return the public finances to a more sustainable footing."

What does a billion pounds look like... and what can it buy?

Nonetheless, Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics, pointed out that the Treasury would not tolerate a 10% deficit indefinitely.

"The timing of the next general election in 2024 suggests that Mr Sunak will not wait until the economy has fully recovered before actively tightening fiscal policy," he said.

"Accordingly, we expect taxes to rise sharply in 2022, in order to attempt to stabilise the debt-to-GDP ratio, while at the same time funding big demography-linked increases in health and pensions spending."

Where does the government borrow?

The government borrows in the financial markets, by selling bonds.

A bond is a promise to make payments to whoever holds it on certain dates. There is a large payment on the final date - in effect, the repayment.

The buyers of these bonds, or "gilts", are mainly financial institutions, like pension funds, investment funds, banks and insurance companies. Private savers also buy some.

You can read more here about how countries borrow money.

Vaccine hope

The latest PMI survey from IHS Markit/CIPS was the lowest for eight months, coming in with an overall reading of 40.6. A figure below 50 implies a decline in activity.

"A steep slump in business activity in January puts the locked down UK economy on course to contract sharply in the first quarter of 2021, meaning a double-dip recession is on the cards," said Chris Williamson, chief business economist at IHS Markit.

"Services have once again been especially hard hit, but manufacturing has seen growth almost stall, blamed on a cocktail of Covid-19 and Brexit, which has led to increasingly widespread supply delays, rising costs and falling exports."

Despite this, the survey also found companies were upbeat about longer-term prospects, thanks to progress being made with the vaccine rollout this year.

- Published22 January 2021

- Published20 January 2021