Waste food: What do you do with 86 tonnes of celeriac?

- Published

- comments

Larger celeriac is usually sold to caterers, leaving a glut of them as they closed for lockdown

Hundreds of thousands of tonnes of food is thrown away in the UK every year. With coronavirus lockdowns closing restaurants, cafes and pubs, there is even more food potentially going to waste. But charities and apps are stepping in.

When wholesaler Philip de Ternant had thousands of pounds worth of food going to waste, charities and buyers queued up to take it off him.

Six thousand pounds worth of milk was among the items at Creed Foodservice that would have to be dumped if a customer couldn't be found for it after schools suddenly closed.

Fortunately, an appeal from footballer Marcus Rashford, external helped publicise the potential waste, and a home was found for the milk.

"We were just pleased to move it through and not have to dispose of it," Mr de Ternant says.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

UK households produce around 70% of the UK's 9.5 million tonnes of food waste every year, according to the charity Waste and Resources Action Programme (Wrap), which is this week launching its campaign Food Waste Action Week to help tackle climate change.

Households are followed by manufacturers, hospitality and foodservice companies. If it isn't eaten, food waste ends up as pet food, compost, fuel for energy production, or in landfill.

The problem has also been exacerbated by the coronavirus pandemic and lockdowns, with wholesalers being affected by the closure of hospitality businesses.

"Sixty-five per cent of business has disappeared. Pubs, restaurants, hotels. All we have left is care homes and schools feeding the vulnerable," says Mr de Ternant.

Philip de Ternant was able to find a home for his surplus milk, and sold other items at a reduced price via an app

But progress is being made as firms with excess produce publicise what they have and a network of volunteers search out those in need.

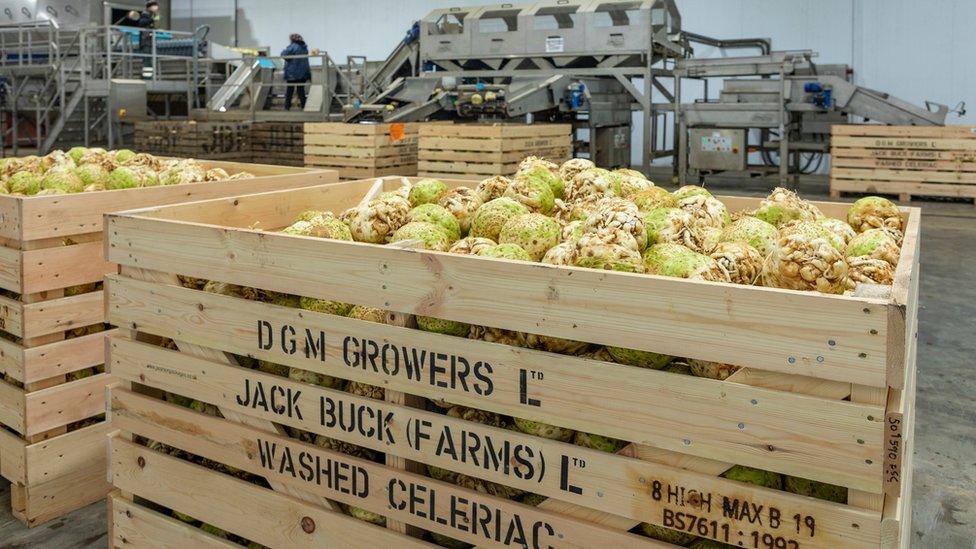

When Simon Scott, general manager at DGM Growers in Kent, had three lorry loads of the root vegetable celeriac spare, he knew he could send them to charity Fareshare, which aims to connect potentially wasted food with 11,000 charities and community groups around the UK.

His company mainly supplies vegetables like celeriac, chicory and fennel to supermarkets, and a move to home cooking has helped his business.

But the lockdown meant he was left with large celeriac usually reserved for restaurants and caterers as they were closed down. He has donated 86 tonnes since October.

"It's provided a significant amount of meals for those in need at this really difficult time. And I think that's really the focus for us, to turn this problem into a positive solution," he says.

DGM Growers donated its surplus celeriac to charity

Food firms from farms to shops are keen to reduce waste, since waste means lost money, says Lindsay Boswell, chief executive of Fareshare.

But waste can arise when mistakes are made in ordering or packaging, through glut, or when a big buyer backs out of a purchase.

Before the pandemic, Fareshare was supplying about 900,000 meals per week to food banks, homeless shelters, school breakfast clubs and community cafes.

Lockdown waste meant they could supply a peak of 3.6 million meals in one week, although the average is back to about 2.2 million.

But despite these huge numbers, demand for food has always outstripped supply, says Mr Boswell, particularly as more people are out of work.

Fareshare gets about a third of its food from shops and supermarkets - food that is coming to the end of its shelf life.

The rest comes from farms, wholesalers and manufacturers.

Fareshare's food comes from supermarkets, growers and wholesalers, says Joanna Dyson

"If you're a grower and you've had a fantastic growing season for tomatoes or beans or courgettes or something, you can see how your orders with the supermarkets are shaping up [and if a glut is on the horizon]," says Joanna Dyson, head of food at Fareshare.

Bounties have included 1,000 tonnes of baking potatoes - enough to fill 50 lorries - which were destined for the hospitality sector; and one million litres of long-life milk, where semi-skimmed milk had been mistakenly packaged in skimmed milk cartons.

Such gigantic donations are often made in stages.

Fareshare has a fund called Surplus with Purpose, which can pay when a farmer or manufacturer has food to donate, but not the resources to deliver it, or where there's a storage obstacle to overcome. About 30% of its food is funded by this scheme.

"So when we had lots of raspberries and blueberries last summer, we were able to send them for freezing. And we've sent apples for juicing," she says.

Local food heroes: Tesco teams up with Olio

There are also apps designed to help make sure surplus food does not go to waste, such as Olio, which last year worked with supermarket Tesco.

Another app, Too Good To Go, allows shops, cafes and restaurants to sell off surplus meals and groceries at a discount.

At Creed Foodservice, wholesaler Mr de Ternant had 2.5kg packages of pigs in blankets on his hands, leftover from Christmas and worth about £15. Shoppers were able to snap them up for £5 via the Too Good To Go app.

Or they could bag £30 of brie, tonic water, pasta sauce and cheese for £10.

Paschalis Loucaides, managing director at Too Good To Go, says: "Since the pandemic began we have looked for ways to ensure that all food, no matter where it is in the supply chain, is eaten and enjoyed instead of wasted.

"When we heard that Creed Foodservice had thousands of pounds of food sitting idle, we knew that we could help."

Related topics

- Published8 January 2021

- Published6 January 2020