How will we heat homes in zero carbon Britain?

- Published

When it comes to winter warming, you can't beat gas central heating. It's been keeping us cosy for more than half a century.

But when your beloved boiler packs up, be prepared for a change - because gas heating can't play a part in zero carbon Britain.

At some date in the future, you will need to install clean heating. And be warned - it won't always be cheap, or convenient.

What's more, we'll have to radically improve insulation, too, because some of the new-style kit can't heat the UK's cold, draughty houses.

There are two main contenders for the £28bn market to heat our homes - hydrogen and heat pumps.

Hydrogen - is that the future of heating?

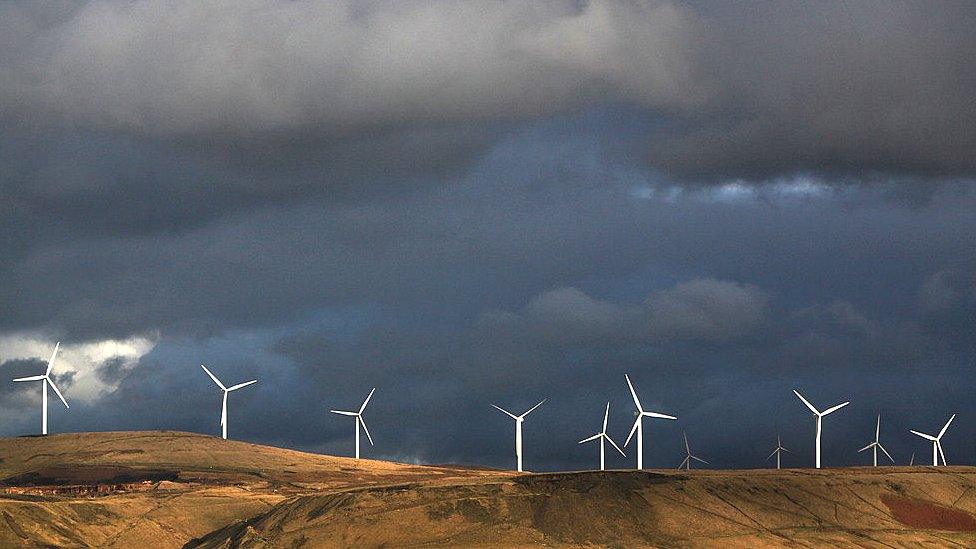

Hydrogen is the most talked-about candidate to replace the gas boiler. Hydrogen can be extracted from water using electrolysis, in a process powered by clean wind power.

Hydrogen lobbyists say it can travel through existing pipes - at least until it reaches the home. And it burns without carbon emissions.

The big firms backing hydrogen say it could heat all of the UK's homes.

But Prof Julia King, from the advisory Climate Change Committee, says that's hot air.

She says that would need twice as much wind power than is currently planned. "That's not going to happen," she says.

Prof King estimates that just 11% of home heating will come from hydrogen.

Heat pumps - are they the future of heating?

Heat pumps are currently used in a few hundred thousand of the UK's homes, and they're largely unknown to the public. Yet the climate committee thinks they will be warming most of our houses in decades to come.

A heat pump is a piece of electrical kit that works like an air conditioning unit in reverse.

Instead of sucking heat from a home and dumping it outside, a heat pump drags residual heat from the ground, the air or a water source and concentrates it to warm the house.

But there may be drawbacks, depending on what type of home you live in. The air-source heat pump can struggle to keep you warm on a very cold night, and the ground source heat pump needs big holes in your garden so pipes can draw out the warmth from the earth.

They're expensive, too, at £10,000 or more - and they may need bigger radiators to be fitted.

Experts say disruption could be minimized by fitting a low-powered heat pump alongside a hydrogen boiler to crank up the temperature in a cold snap.

But even then, Prof King says it will need a big government push and heavy incentives to convert householders from a tried and trusted gas boiler.

"The challenge of heating buildings is a really huge one," she warns. "You have to persuade us to put up with disruption when we have a level of comfort we're familiar with - and it's not clear from the personal point of what the advantage of this new system is going to be."

The answer, her committee says, is a massive government investment in transforming homes with low-carbon heating. It recommends spending £4bn a year into the next decade.

So far the chancellor has committed just £1bn for next year alone under its Green Homes Grant, whereas it's spending £100bn on HS2 rail project that could actually increase emissions.

This issue is considered by environmentalists to be a Treasury blind spot, but the government has promised a heat and buildings strategy soon.

Are there other alternatives - what about wood?

Wood burners were thought to be "green" because new trees soak up the carbon emitted by burning wood.

But they've slipped out of favour because (a) they produce particles that harm people's lungs, and (b) there's not enough land to grow all the wood we would need.

The climate committee says there could still be a few homes with wood boilers in rural areas.

District heating will also play a small part. Fat pipes are laid in the ground to supply heat to housing developments, so houses don't need their own boiler.

The heat could come from, say, a water source heat pump - or it could be waste heat from a factory that would otherwise go up the chimney.

My boiler's packed up - how can I make my home green?

The government's Green Homes Grant, external scheme will fund up to two-thirds of the cost of home improvements, installing insulation, heat pumps, draught proofing and more to help households cut energy bills.

But recent reports, external suggest that the scheme is in disarray, and some installers say customers are pulling out after losing faith in the system.

When I tried to contact installers, I couldn't get anyone to pick up the phone. The number of installers has plummeted since the government withdrew a previous insulation grant scheme.

The government points to other schemes that help organisations promote better insulation.

The Local Authority Delivery scheme, external focuses on owner occupiers and those in the private and social rented sector with a household income of under £30,000. This is designed for low-income households in draughty homes. Councils administer the fund

The Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund Demonstrator, external will support social landlords to demonstrate innovative approaches to retrofitting social housing at scale

The government will improve efficiency of new homes with a Future Homes Standard, external, from 2025. This scheme is nine years behind its original schedule.

The government is also consulting on improving the energy performance of privately- rented homes, which have been the focus of sharp criticism from warm home campaigners.

Heat creates about a quarter of the UK's climate-warming emissions, so critics say ministers must tackle the issue with urgency.

Follow Roger on twitter @rharrabin

Related topics

- Published18 November 2020

- Published20 April 2021

- Published10 July 2020