Budget 2021: 'My benefits top-up is a lifeline - don't take it away'

- Published

Freelance camerawoman Ester de Roij's last commission was cancelled just before lockdown in March

"Twenty pounds doesn't sound much - but it's been a lifeline," says Ester de Roij. "When you haven't got much, taking away a little is a lot."

The freelance wildlife camerawoman is referring to a highly-charged debate over Universal Credit (UC) and plans to trim payments by £20 a week.

Last April, Chancellor Rishi Sunak introduced a £20 uplift to UC as part of his economic support measures, with Ester one of about six million people benefitting.

But the top-up was for a year only, and is due to end in March unless the man who controls Britain's purse strings agrees an extension in next week's Budget.

Ester says that before lockdown, after years of hard work, her career was just starting to pay financial dividends. Now she lives with the anxiety that comes with counting the pennies.

She hasn't worked since December 2019, and her last commission was cancelled a week before the first lockdown in March. Apart from a possible job in August, there's nothing on the horizon.

"I know it might sound odd to some people, but when I got that extra £20 a week it offered a little glimmer of hope," she says. "It's like that glimmer of hope is being taken away."

Bristol-based Ester says UC provides "just enough to cover the rent and some bills". Everyday expenses come out of a government-backed bounce back loan, meagre savings, and help from family."

She is one of the UK's so-called 'excluded', the estimated 2.9 million self-employed who are not entitled to any of the lockdown grants.

She said: "I consider myself lucky to get UC, because 60% of those excluded haven't even been able to access that. I am worse off than 90% of the country purely because of the pandemic, but with UC I am also in the minority within the excluded community. Without it, I don't even want to consider where I would be."

'Scarring effects'

Charities, trade unions, religious groups, and MPs from all parties have called for a top-up extension. Without it, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimates, 500,000 more people will be driven into poverty.

Stephen Timms, Labour chairman of the Commons Work and Pensions Committee, says not extending payments would be "a failure to recognise the reality of people struggling".

The Resolution Foundation think tank says poor families will be among the last to benefit from economic recovery

The debt counselling charity Christians Against Poverty (CAP), which deals with some of Britain's most financially vulnerable, says not having enough money to live on has long-lasting scarring effects on people and economies.

CAP's social policy manager, Rachel Gregory, says: "We see how debt impacts people's mental and physical health, as well as causing relationships to break down and social isolation.

"Lockdowns have had a really polarising effect. It has been higher income households who have built up lockdown savings, whereas lower income households have been more likely to see their hours cut and incomes fall."

In January, a study by the Resolution Foundation think tank, external found that poorer households are, in fact, spending more during lockdown, not less.

With schools closed, the poor spend more on food, energy, and entertaining children. Lockdown and health concerns mean more people must use expensive local shops and online supermarkets, the Resolution Foundation says.

It's true that savings ratios - the amount of disposal income set aside - have soared as people spend less on, say, holidays, childcare or eating out. But these were costs rarely incurred by the poor in the first place.

'There's no work'

When single father Anthony Lynam got his £20 increase the money was just rolled-up into his weekly budget for essentials - more food for his two young children (8 and 3) or clothes to meet their fast-growing needs.

"It was not a solution to everything, but it was a massive help," says the former retail worker from Northampton. "Households have come to rely on this money. No one uses it for anything fancy. You're still on the breadline all the time."

He was already using food banks and sharing pages on social media. But his debts got so bad that he had to file for personal bankruptcy.

That means his savings are long gone, and there's no possibility of a loan or overdraft. "Never did I think things could get quite so bad. I became quite ill [with depression]," says Anthony.

He lives on a housing estate and says everyone is trying to survive on UC. "I don't think the government knows just how serious things are. It won't be long before the only reason we leave the house is to go begging on the streets. There's no work."

Critics of the top-up don't deny the vulnerable need help. But they argue such across-the-board benefit rises are a wasteful use of taxpayers' money.

Professor Len Shackleton, research director at the Institute for Economic Affairs (IEA), a free market think tank, says the top-up did not distinguish between people in need after losing jobs due to lockdown and longer-term benefits claimants.

Political compromise

It was also meant to be a temporary measure in expectation of a quick end to lockdown, he adds. "If we could imagine that the pandemic had never happened, would any serious government have increased a key benefit by £20 a week at one go? It would have been unprecedented.

"The uplift was meant to protect people who faced serious short-run disruption to living standards as they unexpectedly became unemployed or had working hours sharply reduced. Those on long-term UC did not really face the same problem, but they got the extra anyway."

Prof Shackleton thinks a "political compromise" might be to continue with a lower uplift of, perhaps, £5 a week, and to give new entrants to unemployment a one-off £500 payment.

Neither the Treasury nor the Department of Work and Pensions (DWP) would be drawn on the future of the payments and options being considered.

A government spokesperson told the BBC that protecting the economy, jobs and health had been a priority during the pandemic and it would continue to assess the measures needed.

"We are committed to supporting the lowest-paid families and those most in need," the spokesperson said, adding that in 2020 the government spent more than £100bn on working-age welfare, the highest level on record.

'I deserve a break'

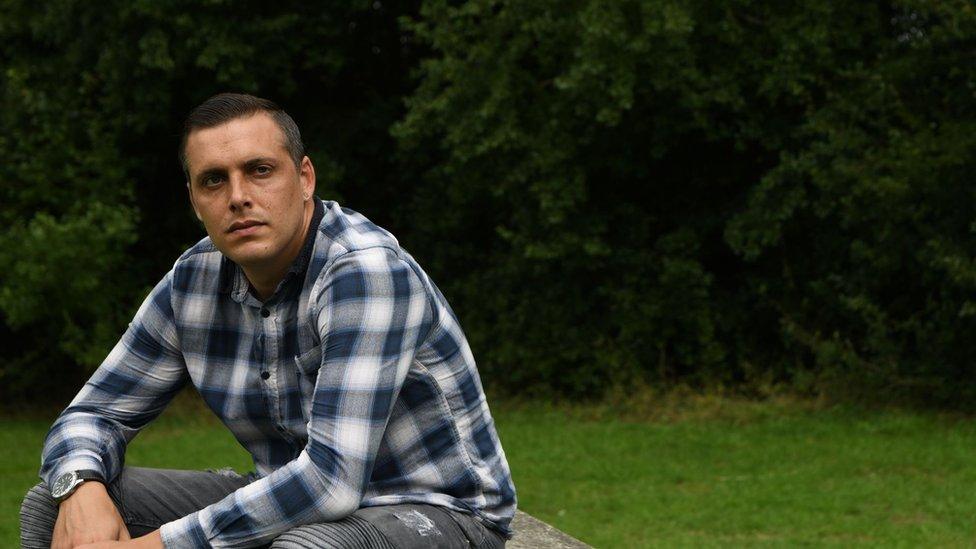

Ron Graham has a message for Boris Johnson: "If you need to make cuts, [UC] is the wrong place to look. You won't have faced my circumstances, but £20 means so much to people in my position."

The collapse of his decorating business was compounded by being "dumped on" by a friend. "I acted as a guarantor for someone, but it went wrong," he says. The toll on his mental health was severe.

"Losing £20 a week would definitely have an impact," says the 62-year-old. "Once you budget for having that money, taking it away has consequences - less food, less fruit and veg."

On day, when his work - and mental health - pick up there may come a time when he no longer needs to rely on the uplift. For the moment, he certainly does.

His monthly outgoings are about £760, including £450 to rent his flat, in Irvine, North Ayrshire. "I only get £350 towards my rent, so the £20 is how I make up any shortfall. I have very little to live on.

"I would ask people not to be judgemental. You don't know what people are going though until you have walked a mile in their shoes. I deserve a break."

Earlier this month DWP Minister Will Quince, speaking in the Commons, criticised what he described as "unhelpful scaremongering" over UC, saying discussions "remained ongoing" with Treasury.

But the speculation continues. Media reports this weekend claimed the £20 top-up will be extended for six months, with the plan awaiting sign-off by the prime minister.

Another idea under consideration was giving a lump sum payment to claimants, although this now appears to be low on the list of options amid concerns about possible fraud risks.

'Right thing to do'

Whatever the decision on the top-up, though, some economists believe the plight of poor can only get worse.

A Resolution Foundation study published last week, external lays bare the future financial hit to families claiming UC, with 61% saying they will struggle to keep up or will fall behind on bills over the next few months. That figure is about twice the proportion of families across the economy as a whole (31%).

It's wrong, says Resolution Foundation chief executive Torsten Bell, to remove £1,000 a year from more than six million people at a time when unemployment is set to reach its peak.

"That's not a society building back better. It's one growing apart. Continuing the uplift is the only right thing to do," he says.

- Published13 May 2024

- Published13 January 2021

- Published20 January 2021

- Published18 February 2021