UK finances see first January deficit in 10 years

- Published

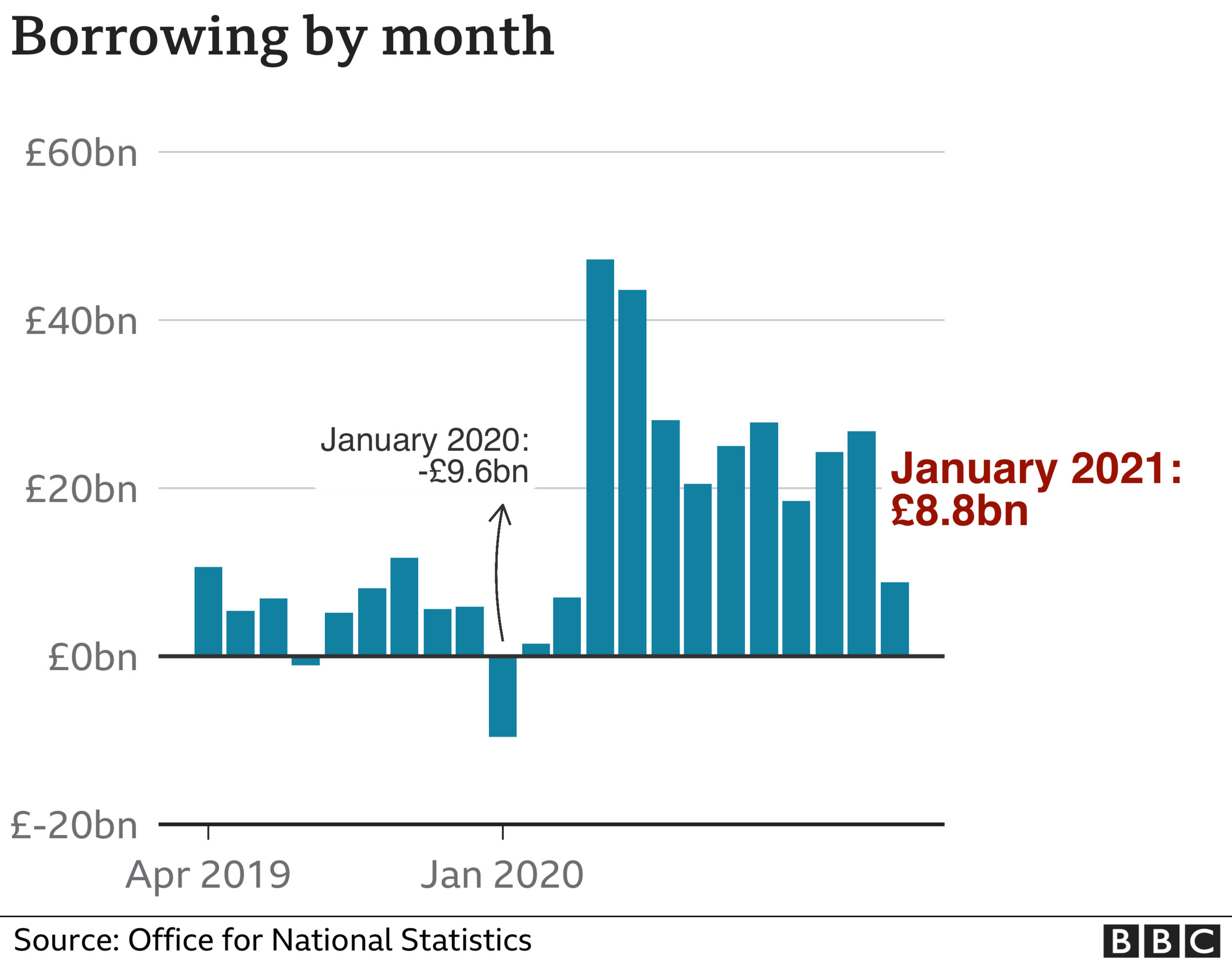

UK government borrowing hit £8.8bn last month, the highest January figure since records began in 1993, reflecting the cost of pandemic support measures.

It was the first time in 10 years that more has been borrowed in January than collected through tax and other income.

January is usually a key revenue-raising month as it is when taxpayers submit their self-assessment returns.

Tax income fell by less than £1bn, but the government spent £19.7bn more than last year on measures such as furlough.

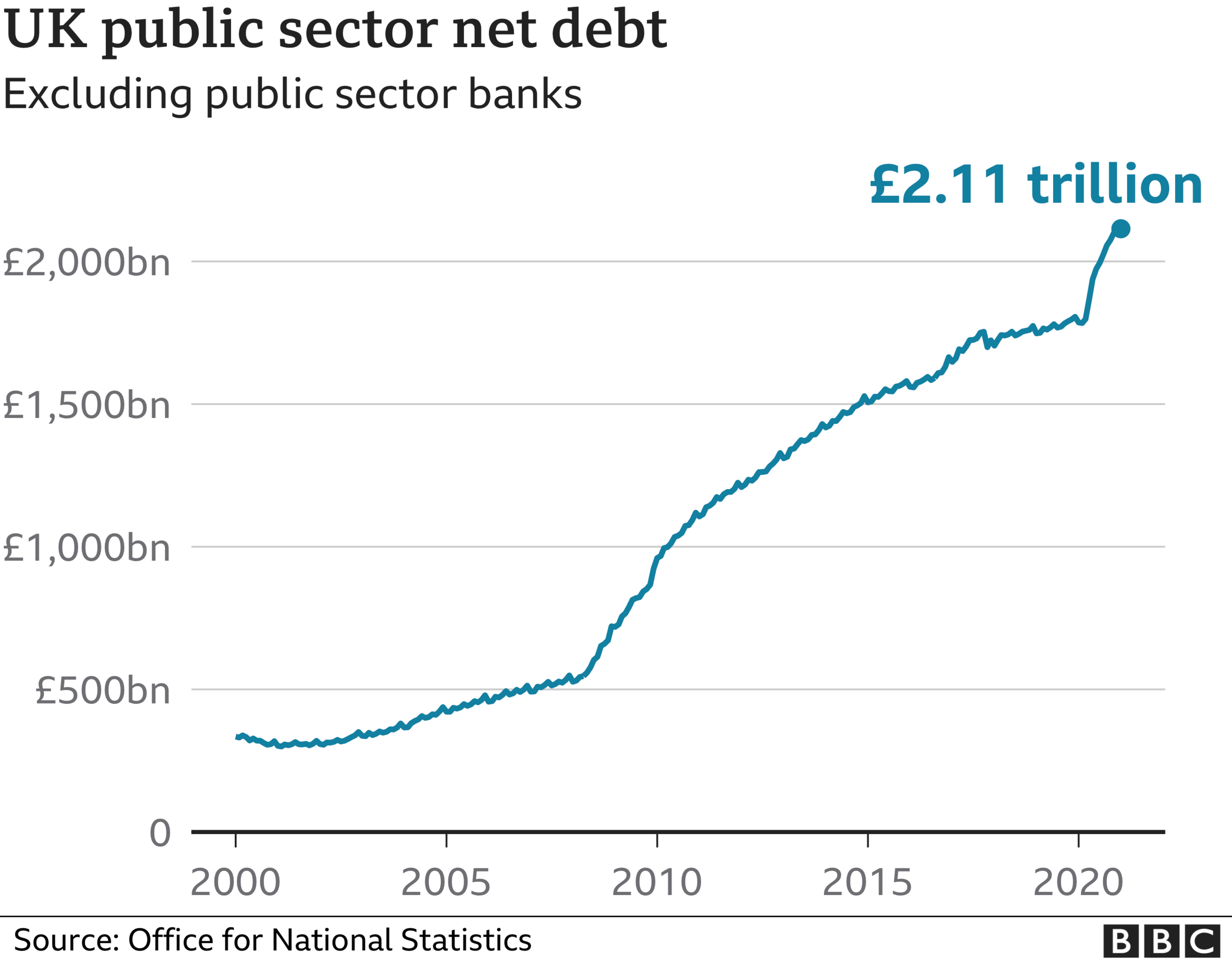

Government borrowing for this financial year has now reached £270.6bn, which is £222bn more than a year ago, said the Office for National Statistics (ONS),, external which published the data.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) has estimated that borrowing could reach £393.5bn by the end of the financial year in March. That would be the highest amount in any year since the Second World War.

The borrowing figure was lower than expected but that "should not be interpreted as a signal that the economy is withstanding the third lockdown relatively well", said Samuel Tombs, chief UK economist at Pantheon Macroeconomics.

"A sharp £2.1bn year-over-year decline in interest payments, and the vanishing of contributions to the EU's budget, which totalled £2.2bn in January 2020, helped," he pointed out.

The increase in borrowing has led to a steep increase in the national debt, which now stands at £2.11 trillion.

The UK's overall debt has now reached 97.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) - a level not seen since the early 1960s.

The ONS warned that although the impact of the pandemic on the public finances is becoming clearer, "its effects are not fully captured" in the current data, and that its estimates of tax receipts and borrowing are "subject to greater than usual uncertainty".

It is an almost unbroken rule - January is a time when the Treasury coffers fill and more is paid in than is spent.

But for the first time since the financial crisis, the Government had to borrow money in January to make up the gap between what it spent and what it raised in taxes.

This near £9bn deficit though was actually better than expectations of £25bn of January borrowing. Receipts from taxes on workers and businesses held up on last year.

The borrowing was mainly about £8bn extra spending on things like vaccines, protective equipment and testing, and support for jobs and wages up £5bn on last January.

Over the course of this financial year the public finances are heading for borrowing of around £350bn - less bad than forecasts closer to £400bn, but still a peacetime record.

This is the backdrop to the chancellor's budget in a fortnight, where he vows to be open and honest with the public about this challenge, suggesting tax rises at some point. The immediate focus though will have to remain on supporting the economy, as it is cautiously reopened.

Hospitality companies have been excused from paying business rates and home buyers have had a break from paying stamp duty since July. Both these factors meant a drop in revenue for the government.

But alcohol duty has risen by a quarter and self-assessed income tax receipts were £1.4bn higher.

Overall, tax income fell about 1% to £80.3bn.

Some of the self-assessed income tax gain probably came from the government's policy of allowing some later payments that were due from July, the ONS noted.

In the 10 months to January, self-assessed income tax receipts were £26.3bn, £2bn less than in the same period a year earlier.

More than has been £46bn spent covering salaries as part of the furlough scheme, and tens of billions of pounds on guaranteeing loans to businesses.

In all, the Government has launched more than 40 schemes across the UK to help households and businesses through the coronavirus crisis.

Chancellor Rishi Sunak said: "Since the start of the pandemic we've invested over £280bn to protect jobs, businesses and livelihoods across the UK - this is the fiscally responsible thing to do and the best way to support sustainable public finances in the medium term."

Tax rises, eventually?

In his Budget on 3 March, "the Chancellor likely won't shy away from setting out plans for borrowing to remain very high in 2021/22, probably close to 10% of GDP," said Mr Tombs.

He predicted that the chancellor will also be able to avoid setting out future tax rises for 2022 and beyond, if the OBR maintains its upbeat view on the amount of long-term scarring caused by the recent downturn.

But he warned that upward pressure on spending will increase over the coming years as the population ages and the Conservatives invest more to "level up" the country.

"As a result, big tax rises eventually will have to be announced, with 2022 likely to be the worst year," said Mr Tombs.

The Budget will aim to secure the recovery, not to fix the public finances, the Institute for Fiscal Studies said earlier this week. That means substantial tax rises should not be part of the coming Budget, it said.

"Rishi Sunak needs to strike a balance between continuing support for jobs and businesses harmed by lockdowns, and weaning the economy off blanket support which will impede necessary economic adjustment," said Paul Johnson, IFS director.

"For now, Mr Sunak needs to focus on support and recovery. A reckoning in the form of big future tax rises is highly likely, but not as yet inevitable."

Related topics

- Published18 February 2021

- Published17 February 2021

- Published22 January 2021