How can we make washing machines last?

- Published

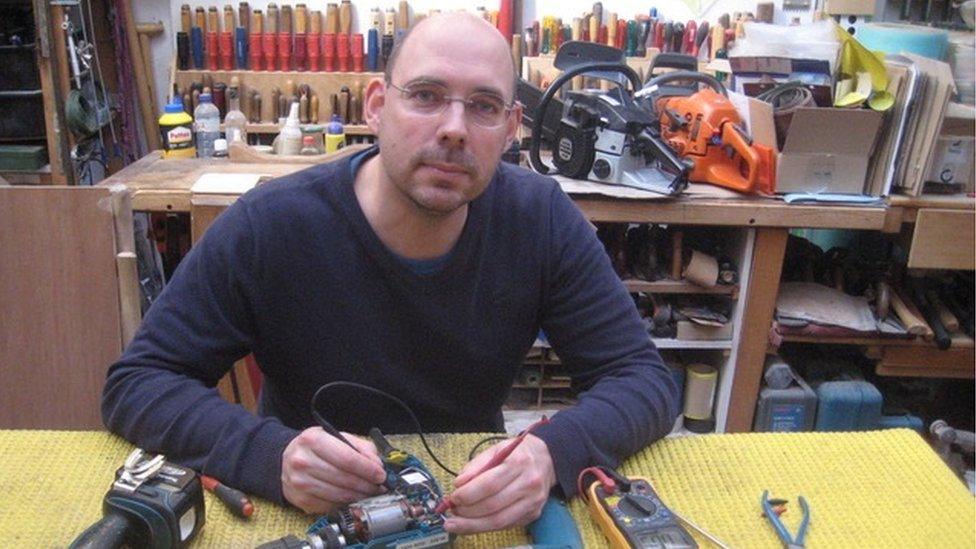

Johan Rääf benefited from a Swedish tax break designed to encourage repairs

When his family washing machine stopped working just a few months outside its warranty, Johan Rääf was less than impressed.

"It was really strange because it's not been used every day, or not even that much," says the 36-year-old from Stockholm.

Like many Swedish parents, Mr Rääf deals with the constant stream of laundry generated by his two small children by using the larger communal washers available in his apartment block, alongside the machine in his own flat. "So, it was a problem that needed to be fixed, but it wasn't like my life depended on it," he laughs.

He paid a local repair firm 1,500 Swedish krona (£130; $180) to provide and fit a replacement part the following day; making use of a Swedish tax break which halves the cost of hiring people to repair white goods in your home.

But fixing things that break down often isn't that easy, cost-effective or even desirable. Most of us tend to replace things that break instead of mending them.

According to iFixit, which campaigns for the right-to-repair, at least 30% of electric and electronic products are discarded when they are still in a repairable state. This kind of rubbish is becoming one of the world's fastest growing waste streams.

Many customers don't repair household items simply because they have become more affordable to produce and buy new, in recent decades, says Thomas Opsomer, a spokesperson for iFixit.

He estimates that the price of a new washing machine adjusted for inflation is between 10 and 20 times cheaper now than it would have been in the 1960s.

"If a new appliance is very cheap, then already that makes the case for repair harder," he says.

Jessika Luth Richter says it has become fashionable to upgrade devices

At Lund University in southern Sweden, sustainable business researcher Jessika Luth Richter says there's also been a big cultural shift in how we value things we own.

We live in an "age of fast consumption" where gadgets have become viewed as "disposable" and "it's fashionable to upgrade our products to the latest models available", she says.

Meanwhile, brands are in tough competition with one another, and seek to lure us in with special offers and speedy delivery options to encourage us to buy new products and enjoy the "instant gratification or instant hit".

Washing machine makers might not agree with that. Britain's Ebac already designs its washing machines to last 10 years. Founder and chief executive John Elliott thinks most washing machines are "quite well built", but does have his doubts about the cheapest ones on the market.

"There's some cheap washing machines - they sell them at a price lower than we can buy the components. That tells you something, doesn't it?"

John Elliott says most washing machines these days are well made

While Mr Rääf was able to find a company in his Stockholm neighbourhood to fix his washing machine, Ms Luth Richter says the number of local repair stores has fallen across Europe, as our appetite for this kind of fast consumption has grown.

That means even customers who want to live more sustainably can find it hard to source the expertise to fix broken products at an affordable price. iFixit's research suggests people aren't willing to pay repair costs that amount to more than 30% of the price of a new product.

"What most of them are feeling is that they don't know what it will cost and they don't know when they can get it [repaired]. And that makes all the difference," agrees Måns Ljungmark, a manager at Swedish appliance brand Electrolux, which has its headquarters in Stockholm.

The company's actively trying to encourage more customers to fix broken products as it tries to become a more sustainable business. It has increased its online and phone advice, to help enable customers to carry out simple repairs themselves. Plus, it is trialling a £150 (1,785kr) flat fee repairs service in parts of Sweden and in Denmark.

"We are taking a risk because some repairs are more expensive and some repairs are less expensive, because we want to enable repairs," says Mr Ljungmark. The initiative could drive down profits from new sales, he accepts, but he hopes the business will still benefit in the long run, from "building loyalty and trust".

Måns Ljungmark from Electrolux says his company wants to encourage repairs

So far the flat-fee service is proving popular, with a 20% increase in bookings during 2020. In Sweden, it's been enabled by the same tax break Johan Rääf used to fix his washing machine. White goods repairs have increased steadily since they were included in the scheme (known as ROT) in 2017, and jumped by 16% in 2020.

There's a lack of data on customer motivations, but the Swedish Tax Agency and manufacturers like Electrolux speculate that job losses and economic uncertainty brought on by the pandemic may be encouraging more people to repair rather than splash out on newer products.

Sustainability campaigners want more countries to offer similar tax incentives or other "economic levers" to help promote repairs. But with public finances already squeezed during the pandemic, that could be a challenge even for governments with a strong environmental agenda.

Another method is punishing manufacturers that make it deliberately tricky to repair products. In the EU a new law has just come in, forcing firms to supply spare parts for machines for up to 10 years and to design products to make them longer-lasting. The rules apply to washing machines, dishwashers, fridges and lighting. Repairs should be possible with commonly-available tools and without damaging the product.

Campaigners say it is a step in the right direction. But the law doesn't specify anything about the price of parts. Plus only professionals, not consumers, will be able carry out the repairs, a move backed by manufacturers who were worried about risk and liability.

Thomas Opsomer from iFixit worries that devices are getting harder to repair

At iFixit, Mr Opsomer is also worried that as products in our homes become more high-tech and connected, this could "introduce new possibilities for failure and make things harder to fix".

But manufacturers like Electrolux argue the opposite. Måns Ljungmark says that as our household products become smarter, this will actually help enable repairs and longevity. For example, if your dishwasher can suggest when you need to rinse a filter, this may prevent a future breakdown.

However this still leaves consumers with a dilemma: buy a shiny new smart product designed to enable sustainability, or repair something older with fewer functions.

Sustainability specialists insist it is almost always both cheaper and more sustainable to stick with what you've got. If you throw away a product, you're both contributing to the two billion tonnes of rubbish the world generates each year, and adding to the planet's carbon footprint by buying a new item, often made from newly-mined materials.

But experts are split on whether profit-driven companies or fast-consuming customers will really be able to adjust their habits.

"As long as it is more profitable for a company to sell a new product than to repair that product, a company will be under very much pressure from their shareholders to do just that," argues Mr Opsomer.

Jessika Luth Richter is more optimistic that it will become both easier and trendier to fix stuff in future. "The more people that are repairing and are choosing to buy repair services or more repairable products, the more we will see this becoming mainstream," she says.

"And it used to be mainstream. So that's what makes me positive too, that. It is in some ways a return to what we used to be able as a society to do more of."