Myanmar coup: Could sanctions on the military ever work?

- Published

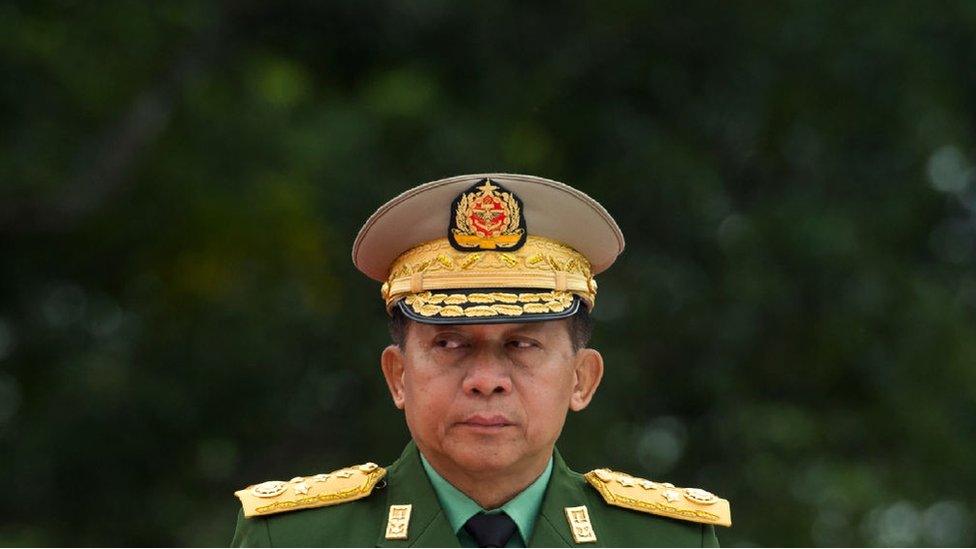

As violence against Myanmar's civilians mounts, Western powers have been ratcheting up economic pressure on the country's military following its internationally condemned coup on 1 February.

The US and UK, for instance, have imposed sanctions on Myanmar's two military conglomerates - Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) and Myanmar Economic Holdings Ltd (MEHL) - which control significant portions of Myanmar's economy and have interests across many major industries.

The US Treasury Department has also blocked assets and transactions with Myanmar's state-run gem company, a key source of income for the military authorities, while the EU has imposed sanctions on several individuals linked to the military.

Human rights groups and democracy activists have long pushed for sanctions, arguing that they fund the military's repression of protesters. More than 600 people have been killed by security forces since the coup began.

"These actions will specifically target those who led the coup, the economic interests of the military, and the funding streams supporting the Burmese military's brutal repression," Secretary of State Antony Blinken has said. "They are not directed at the people of Burma."

But while the West, most notably the US, has been keen to take the lead in imposing sanctions, Myanmar's biggest trade partners in Asia have rejected that approach.

Critics worry that the uneven pressure won't be enough to force change.

"The leverage is not really there," said Richard Horsey, a Myanmar expert with the International Crisis Group.

Do these apartments fund human rights abuses?

One example that lays out the complexity of imposing sanctions and enforcing them is Golden City, a Yangon mixed-use development with an unobstructed view of the city's most famous landmark Schwedagon Pagoda.

The activist group Justice for Myanmar says the development is a cash cow for Myanmar's military that channels millions into the military department "which buys weapons of war that are used on the people of Myanmar in the commission of war crimes and crimes against humanity."

Singapore-listed company Emerging Towns and Cities (ETC) - which owns a 49% stake in the development through a number of local companies - halted trading in February after Justice for Myanmar published the allegations, and the stock exchange demanded the company explain its part in the project.

The company admits its partner in Myanmar has ties to the military. It makes lease payments for Golden City into an account administered by the Quartermaster General's Office, which reports to the Ministry of Defence.

But ETC denies those funds could have been used to commit human rights abuses, saying that under Myanmar law, the Quartermaster General must turn over all funds to the government's budget account. And it told the Singapore stock exchange (SGX) that's where its responsibilities end.

"The company is entitled to assume that the application of funds administered by Myanmar government ministries is in conformity with existing provisions of Myanmar law, and as such, makes no comment on the actual use of the lease payments it is obligated to make," ETC said in its responses to questions from the SGX.

The company suspended trading in early March on the Singapore exchange while it seeks out an "independent" review to clarify its dealings in Myanmar to investors.

ETC declined interview requests, and Myanmar's embassy in Singapore didn't respond to requests for comment.

The row over the development is a reflection of the fragmented international response to the 1 February coup. Activists might cause headaches for ETC, but the company can't be in breach of sanctions because Singapore hasn't imposed any.

Will sanctions work?

Both critics and proponents of a tougher approach agree that up until now the sanctions - which only targeted Myanmar's top brass - have been fairly weak.

"The Myanmar military are not going to fall down on the floor, cry and say 'oh my god, I've lost my visa to the US, my life is over'. They'll probably laugh," said Kishore Mahbubani, a former Singapore diplomat and a Distinguished Fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore.

More broadly, sanctions as a policy tool have a patchy record.

Researchers from the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) evaluated over 200 cases and found that only a third were a complete or partial success, external. Others using the same data put the hit rate at just 5%, external, arguing the PIIE researchers were too generous in their definition of success.

Their track record in Myanmar - which was not part of the PIIE study - is hotly debated.

Some say they played a key role in forcing the military regime to release Aung San Suu Kyi and reopen the country a decade ago, while others say they either weren't significant or only made a difference after the ruling junta decided to change course.

Gary Hufbauer, who led the PIIE's research, said sanctions tend to have a higher chance of success against poor countries like Myanmar.

But they tend to be most successful when the goals are modest, the target countries are not autocratic, and they lack external "black knights" who might throw their economy a lifeline.

Could sanctions hurt more than they help?

Previous sanctions on Myanmar have had a humanitarian impact. For example, the US state department estimated that a 2003 US ban, external on Burmese textile imports cost 50-60,000 jobs (although orders from the EU mitigated the effect).

Protester Thuta says he is prepared to die in the fight to restore democracy to Myanmar.

Mr Horsey worries that ordinary people rather than the government could again pay the price, especially if the sanctions turn into a broader attempt to bankrupt the state. But human rights groups say the current sanctions are more targeted than those Myanmar faced previously, and point out that democracy activists in Myanmar are themselves boycotting military-linked companies.

"We're not doing anything that the Myanmar people aren't doing themselves," said Phil Robertson of Human Rights Watch.

Military entanglements

If sanctions are aimed at hurting the military without shutting down the economy, the question then becomes whether or not foreign businesses can still operate in Myanmar while tiptoeing around the two conglomerates.

Htwe Htwe Thein, an Associate Professor of International Business at Curtin University in Perth, said the two businesses are not all-encompassing, and many consumer goods companies could probably continue to operate. But the same isn't true for Myanmar's resources sector.

"The ownership of the military is rampant in there. It's everywhere in the extractive sector," she said.

But if sanctions force western oil and gas companies to withdraw, Mr Horsey expects that businesses from China or Thailand would replace them.

"If companies like Woodside and Total are forced to divest, they're going to have to sell off their assets rather cheaply, and it's pretty obvious who's going to buy them up," said Mr Horsey.

Asean versus the West

China and Thailand account for more than half of the country's trade volume, while Singapore is the single largest foreign investor, generating $11bn over the past five years according to Myanmar government figures.

While the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) has called for a peaceful resolution to the crisis, the group has flatly rejected sanctions.

Mr Mahbubani argues that quiet diplomacy behind the scenes could accomplish more.

"It's the southeast Asian way of avoiding confrontation. And frankly, you have to acknowledge that has kept Southeast Asia at peace for 30, 40 years now, finding diplomatic solutions, talking to each other and changing people's minds," he said.

Phil Robertson attributes Asean's reluctance to self-interest.

"If it was left to Asean, nothing would happen at all," he said.

"And the idea that they're somehow going to be part of the solution is rather laughable".

Mr Mahbubani sees it very differently. He thinks the west's brash, critical approach during the Rohingya crisis, loudly condemning Aung San Suu Kyi for her reluctance to act, may have convinced the military that they could move against her because she no longer had allies. And he thinks it's unlikely that sanctions will change their mind now.

"They are very stubborn people. The more public pressure you put on them, the more they'll dig their heels in," he said.

- Published1 April 2021

- Published21 March 2021