In a pandemic it isn't a case of health v wealth

- Published

Twelve brutal months have supplied one lesson above all: economics cannot be disentangled from health.

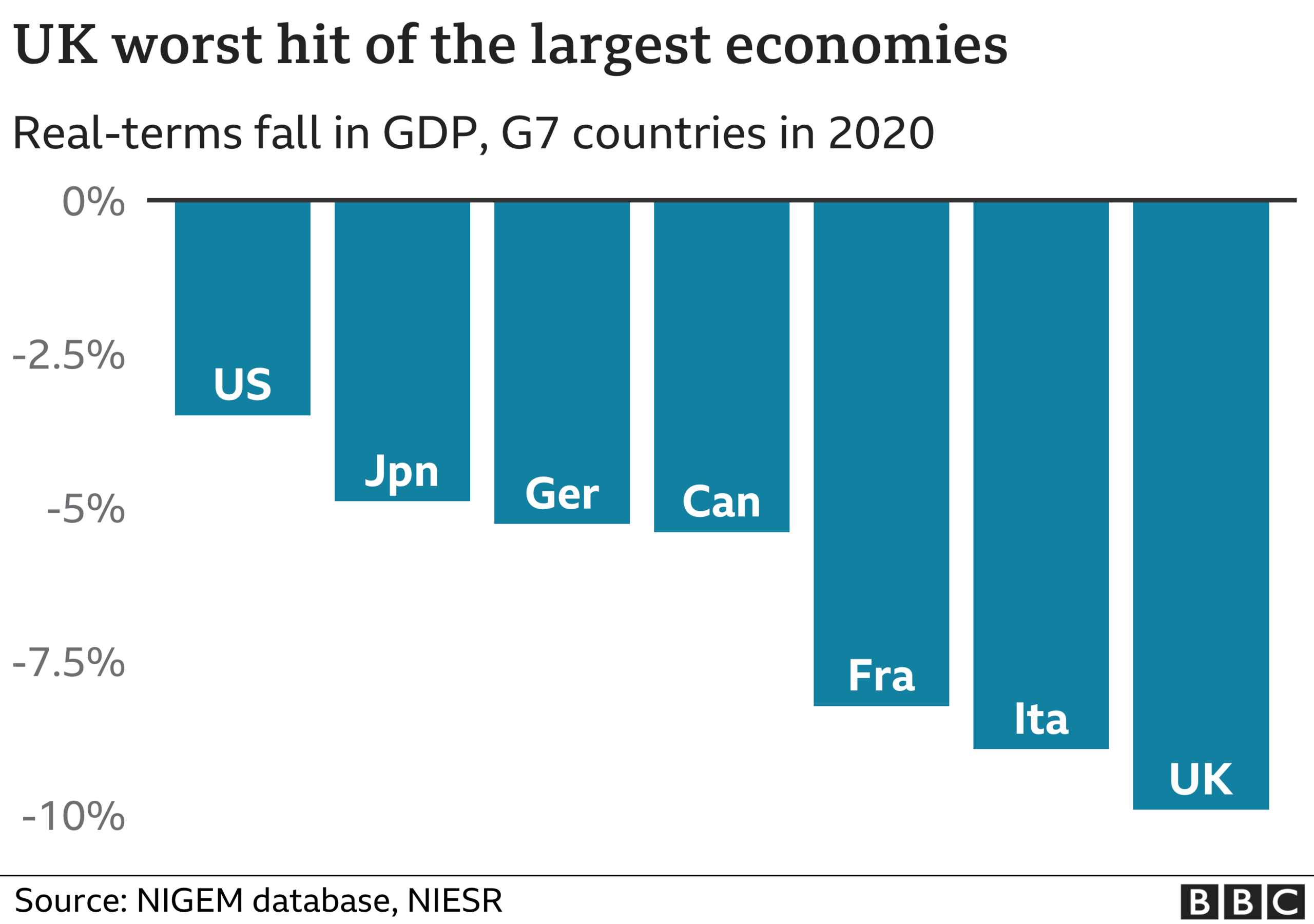

There was never a simple binary trade-off between the two factors: those countries with the biggest first wave of excess deaths, also had the biggest hits to the economy and the UK was the hardest hit of similar countries on both measures within the G7 group of industrialised countries.

That economic picture remains, even after stripping out different methods of measuring the public sector, according to the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) assessment at this month's Budget.

The shape of the recession we saw from the pandemic and lockdowns was extraordinary, historic, but also unique - a very sharp fall with a rapid rebound. Over 2020 the overall numbers saw the largest hit in three centuries. Larger than any single year of the Great Wars or the 1920s Depression.

The UK economy, like Italy and Spain, is particularly exposed to industries where there is social contact, such as restaurants and tourism, that were shut down in the pandemic. But beyond that, as the OBR concluded this month, the primary reason the UK has suffered a greater economic hit is simply that the UK experienced higher rates of infections, hospitalisation and deaths from the virus than other countries, and spent longer in stricter lockdowns.

Decisions to delay lockdowns both in March and then again in the autumn, ostensibly to protect the economy, appear to have led to longer periods under them, with worse overall outcomes.

The big feature of the past year, though, has been the sheer amount of support coming from government. There's never been a recession like it, but there's never been a recession with this amount of spending on protecting jobs and subsidising wages, and supporting business cash flow with grants and loans.

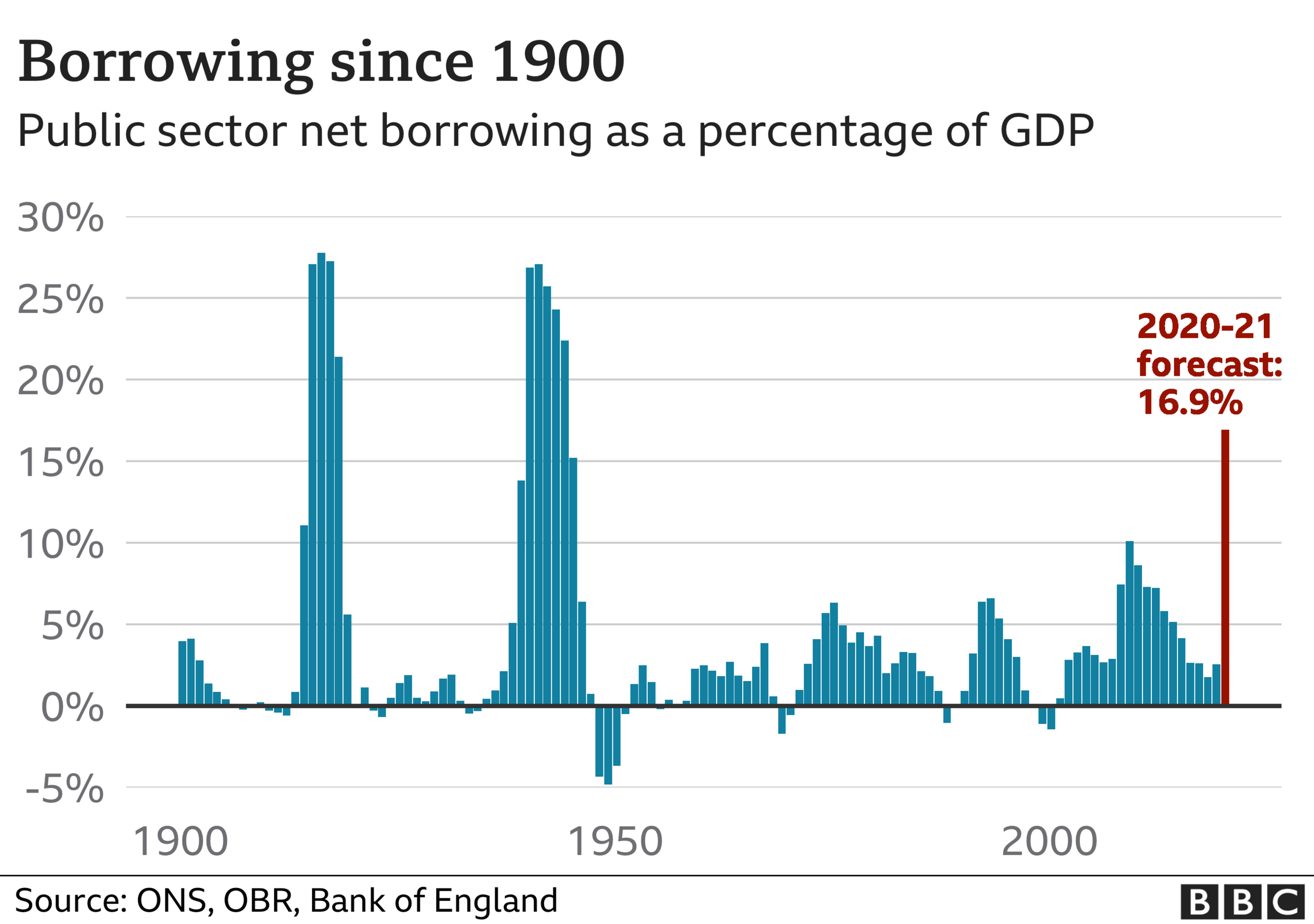

That has meant government borrowing on a scale we haven't seen for decades.

It has clearly limited the rise in unemployment and protected incomes to the point where, for example, overall tax revenues are yet to be significantly hit. While jobless numbers have gone up, most forecasters would have envisaged the level at 8% or 10% by now, rather than just over 5%, with an anticipated peak of 6.5%. So hundreds of thousands of jobs have been lost, but thankfully not millions, which is incredible given the size of the economic shock.

On a visit to Sarginsons, a metal forger in the badly hit car industry in Coventry, they describe the first weeks of the lockdown last year as "bedlam". Eighty of its 89 staff were put on furlough. That was down to 15 in the autumn, and now it is just four.

More important than that, they used the scheme to retrain staff in new cutting-edge 3D modelling and scanning techniques. Mid-pandemic they won new business from the US electric vehicle industry by using a film crew to help a faraway customer connect with its business. And now they look forward optimistically to a changed economy and industry.

Not all companies and industries can manage this. Similar work in, for example, aerospace is still very difficult at a time when few aeroplanes are selling. But this was precisely the point of the support - to bridge over the steep valley of uncertainty, and avoid deep scars for viable businesses.

The early signs are that it did work, though it has cost historic amounts of public money, pushing government borrowing to its highest peacetime levels.

In households, the overall result of this has been that most, but not all, of the population have been cushioned from the impact of the past year. The pain has been concentrated on those working in low-paid ,high-contact sectors. New benefit claims have shot up and are now also disproportionately made by young people.

However, overall incomes have held up, or more specifically, been held up.

Spending, on the other hand, has been restricted in many areas, such as eating out, holidays, and day-to-day travel and expenses. With incomes holding steady that has meant savings have hit record levels, with £180bn higher expected during the pandemic period compared with normal levels.

However, as with incomes, this huge increase in savings overall disguises two very different stories, among different parts of the population, according to an IFS study in the autumn. The poorest fifth of the population had to eat into their savings or borrow to the tune of £170 a month in order to get by, while the rest added to their savings by about the same amount each month.

Incredibly the overall situation of the banking system in the middle of an epic recession, is reassuringly solid, because it has, overall, seen deposits increase by much more than the loans issued to business.

In Coventry town centre this week, people were back, milling around a centre with mainly closed shops and restaurants. There were also notable queues outside banks, caused by the need for social distancing. Unlike the financial crisis a decade ago, customers are mainly putting money into their bank accounts rather than trying to empty them.

But the economy is yet to hit reality. The tide will not go out on this support until the autumn. A fully vaccinated population dangles the promise of a strong economic bounce back. But this will be as much about the voluntary willingness of the public to want to get out and mix and spend, as about the actual lifting of restrictions.

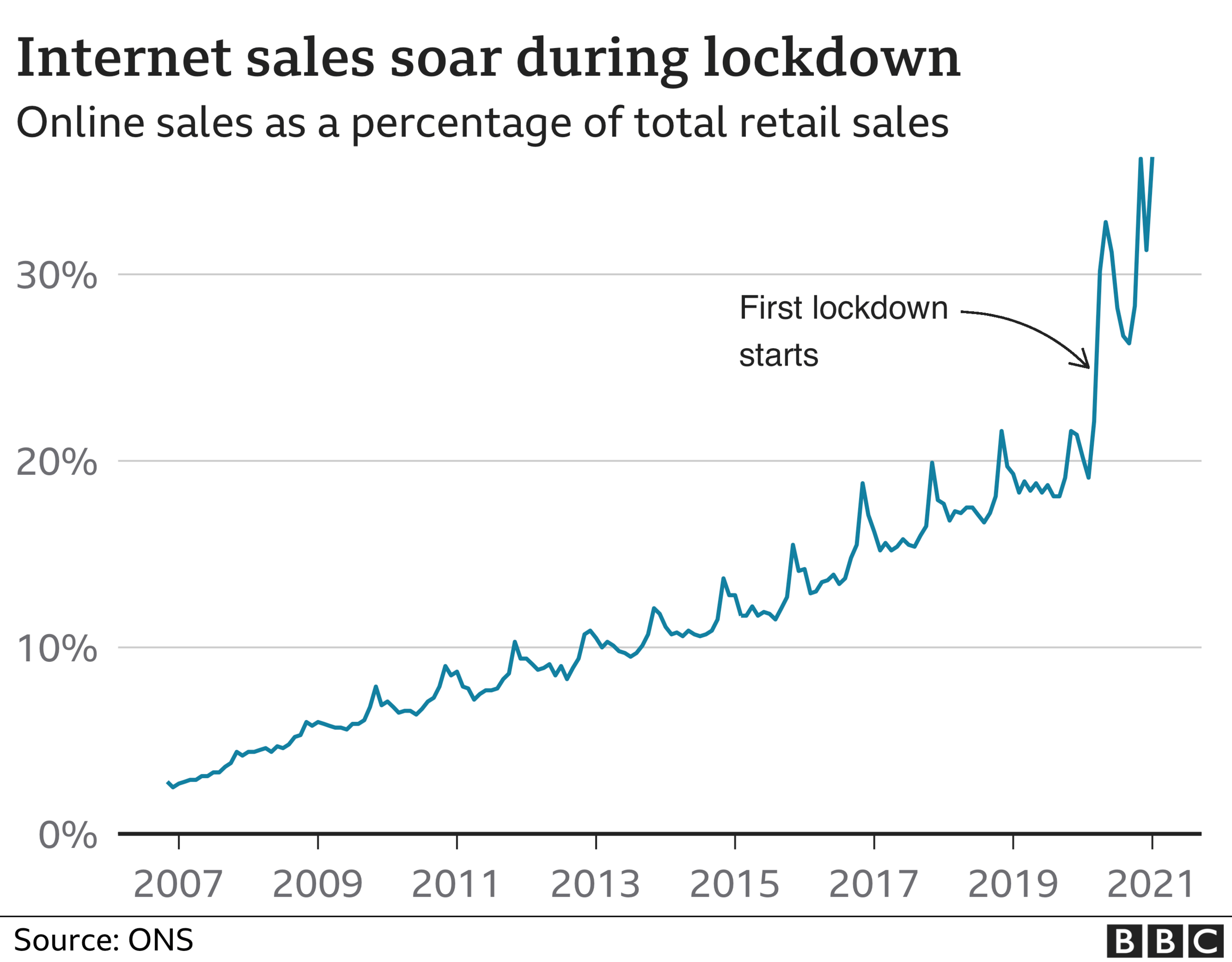

There have been some profound structural changes in the economy. That is obvious on the high streets and town centres, where some of the shops will now never reopen their doors. It took a decade for the proportion of retail sales occurring online to go from 10% to 20% of what we buy. In the past 12 months that shot up to a staggering 36% - about a decade and a half's normal growth in one pandemic year.

The change to the number of foreign workers has also been profound, but no-one knows whether there are hundreds of thousands fewer or well over a million. Either way, should a recovery take hold, there will be big questions around that in the hospitality sector.

In industry, some businesses will have taken the past year to invest in equipment that lessen the need for workers. The Budget's "super deduction" policy will greatly incentivise immediate spending on plant equipment for automation.

This past year has been a catalyst for massive consequential changes and they will create winners and losers. In industry some await the rolling back of support measures, and are already snapping up top talent from other companies, awaiting a process where they can poach their competitors' customers. The full implications of these changes will only be revealed when rescue support is removed.

So significant could some of these changes be that it is unclear that all the support will be rolled back quite so quickly. For now the government has focussed considerable efforts in the current acute crisis phase of the pandemic. The US has, for example, pumped support in right now, as its economy begins recovery.

Economic hits such as we have seen, can profoundly change the economy and the state's responsibilities around health and social support. As the health challenge becomes manageable, the economic challenge around the shape of the recovery will be no less profound.

- Published9 March 2021

- Published9 March 2021

- Published3 March 2021