Covid: February redundancy plans fall despite lockdown

- Published

- comments

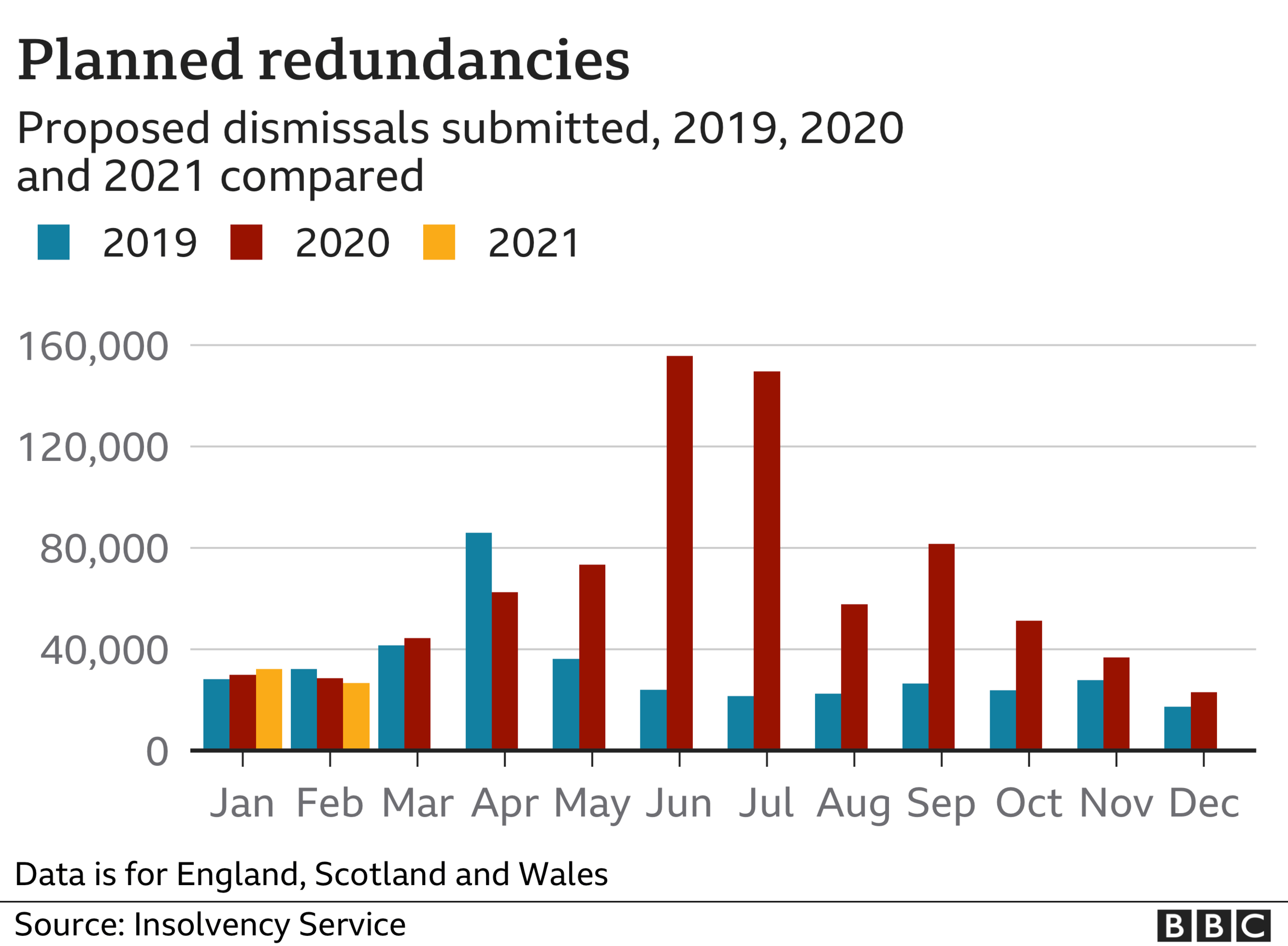

British firms planned fewer job cuts last month despite many being forced to close by Covid lockdowns.

About 26,600 jobs were put at risk, one-fifth below January's figure and slightly lower than February 2020.

The numbers suggest that government support schemes have helped prevent the mass redundancies seen in the first lockdown.

The figures from the Insolvency Service were obtained by a BBC Freedom of Information request.

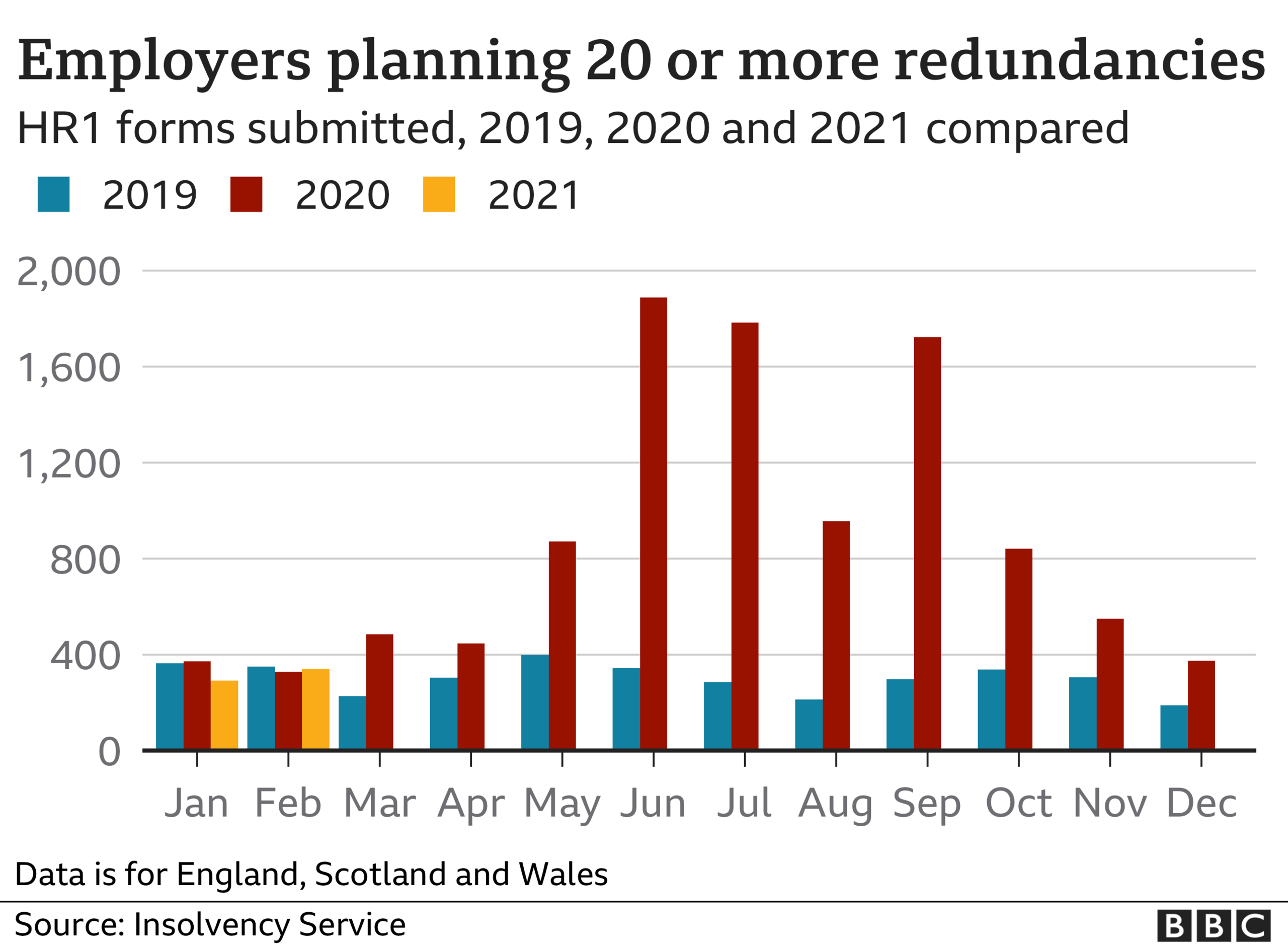

Employers planning 20 or more redundancies have to notify the government via the Insolvency Service by filing a form called HR1.

Because these filings happen at the start of the redundancy process, they give an early indication of labour market changes months before they show up in unemployment figures published by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

The numbers vary considerably from month to month, so it is hard to draw conclusions from small changes.

But there is no sign of a significant spike in job cuts as seen last summer, when businesses were first counting the cost of large parts of the economy being forced to shut.

Government support schemes, such as the furlough scheme where the government contributes to workers' wages at struggling firms, have helped to keep redundancy and unemployment figures down.

At least 4.7 million workers were on furlough at the end of February, according to provisional figures from HMRC.

In March, the chancellor announced that furlough would be extended until the end of September. But experts fear that unemployment and business failures will increase again as government support is withdrawn.

"A lot of those firms are not going to be able to afford to pay the full wages after 30 September," says Dr Nicola Headlam of Red Flag Alert, a company that monitors the financial health of companies.

"Without furlough, a lot of those jobs are gone. There is going to be a lot of shakeout."

Furlough - a stressful 'Godsend'

The Real Food Cafe - on the road to the Highlands

For one rural restaurant on the road to the Scottish Highlands, the furlough scheme has been a lifeline.

With only 150 people in the village, the Real Food Cafe in Tyndrum depends almost entirely on travellers - and that trade all but dried up when the pandemic hit.

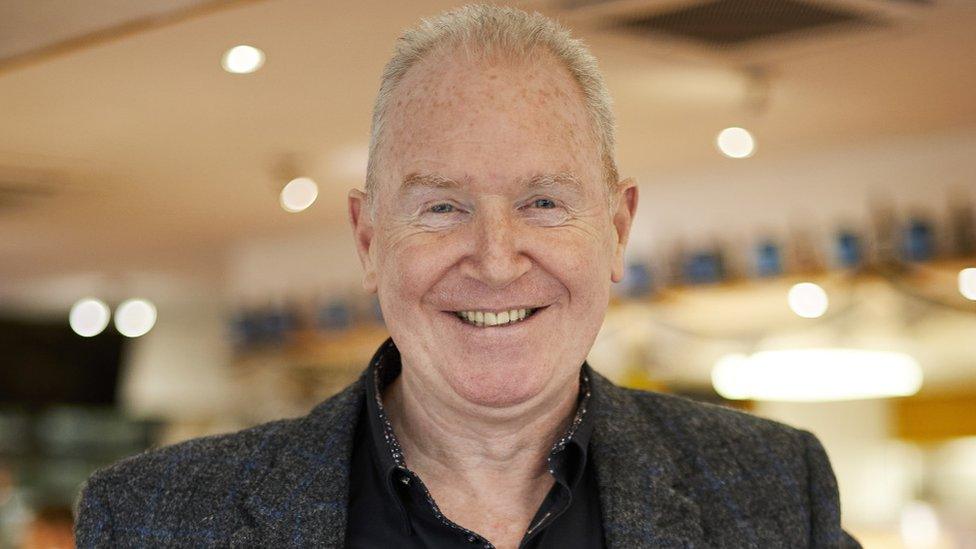

It has 21 full-time staff who will have spent 44 weeks out of 60 on furlough by the time they reopen in April, says co-owner Alan McColm.

Without furlough, he would have had no option but to make his staff redundant, help them as much as possible, and hope to hire them back once the business reopened.

Alan McColm co-owns the Real Food Cafe

Avoiding that has been a "godsend", he says.

Attracting workers to his beautiful but remote location is not easy. So if his team did feel they had to leave, it would be tough to replace them.

He is confident that his business will survive and thrive after lockdown. Some of the changes he has made to cope with Covid, such as ordering by phone, will continue to pay dividends for years to come.

Nonetheless, keeping those workers on furlough has cost £6,000 a month in national insurance, pension and payroll costs.

And the stress of depending on an ever-changing furlough scheme has taken a toll on his mental health.

"I like to be in control," says the former IBM executive. "And this is the first time I have not been able to remove the uncertainty. That has been the biggest challenge of the whole thing."

The number of firms filing redundancy notifications is broadly unchanged in February at 340. This figure also shows a big decline from the extraordinary levels seen last summer.

Employers only notify government about proposed redundancies, and they often make fewer job cuts than they initially plan.

But because the notifications are only necessary for employers planning 20 or more job cuts, the overall number of redundancies measured by the ONS usually turns out to be higher than HR1 total.

Firms in Northern Ireland file their HR1 forms with the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, external and they are not included in these figures.

- Published26 March

- Published25 March 2021