Could electric tattoos be the next step in body art?

- Published

Tattoo artist Kayla Newell

When Kayla Newell goes shopping for tattoo ink, she brings a UV light with her. The tattoo artist from Portland in the US state of Oregon creates dazzling designs, external using colours that appear to glow under ultraviolet light.

Most people don't realise that many off-the-shelf tattoo inks have this effect, she says. And she discovers new fluorescent hues by waving her UV light over vials of ink on tattoo shop shelves. Ms Newell also avoids pigments that use phosphorous. Although it can cause ink to glow, there are concerns over its health effects.

But Ms Newell dreams of being able to go much further with her designs. In recent years, articles about experimental electronic tattoos with built-in lights and circuitry have fired her imagination. The scientists behind such systems generally aim to use them in a medical context, for example to monitor people's vital signs.

Ms Newell suggests the same technology could have artistic uses.

"You could make things that essentially completely change from one moment to the other," she says.

"Something that would have sparkle, or a light source within it, but then to be able to turn it on or off or change the colour - that would be awesome."

Tattoo artists already use inks that glow under ultraviolet light

She's not alone. There's a whole social media trend, external of digital artists who superimpose virtual light effects over videos of new tattoos, to make it look as though the body art can somehow emit moving colours. Not unlike a mini neon sign imprinted on a person's body.

Unfortunately for would-be cybernetic tattoo artists, technology hasn't quite caught up with this vision yet. Though work is very much in progress.

A real, light-emitting tattoo-like device was recently demonstrated, external by a team of researchers working at the Italian Institute of Technology (IIT) and UCL in the UK. The system is not designed to be embedded beneath the skin but rather stuck on top of it on a piece of paper that peels away once water is applied - just like a transfer tattoo.

Other researchers have discussed similar designs before but Virgilio Mattoli at IIT says his colleague came up with the idea after watching his child play with transfer tattoos.

Here the light is attached to a thin, flexible film that can be attached to the skin like a transfer tattoo

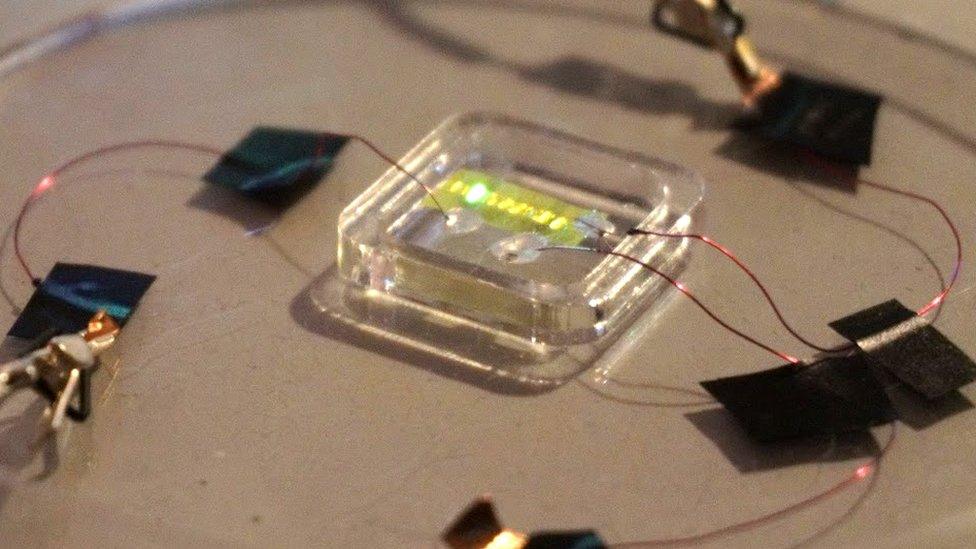

They constructed their device in layers, some of which are deposited by an inkjet printer. Among the components are a layer of acrylic, flexible electrodes, and an organic light-emitting diode (OLED) that glows a greenish yellow colour.

"Since you print this, you can print any shape you want in theory," says Dr Mattoli.

To date, the team has only managed a tiny, square patch of light in a device that works for less than an hour. And they have yet to try using it on humans, though they have tested sticking their tattoo to a strange array of inanimate objects, including a juice bottle, a box of paracetamol and an orange.

Dr Mattoli argues that one day it will be possible to embed all necessary components in the transferable tattoo itself - including a sensor to monitor someone's vital signs such as heart rate or skin hydration, and a power source to keep the device working for a few hours, at least.

The prototype may be an early step but among those who are excited by it is Nick Williams, a PhD student at Duke University in the US. "I think it's an impressive demonstration," he says.

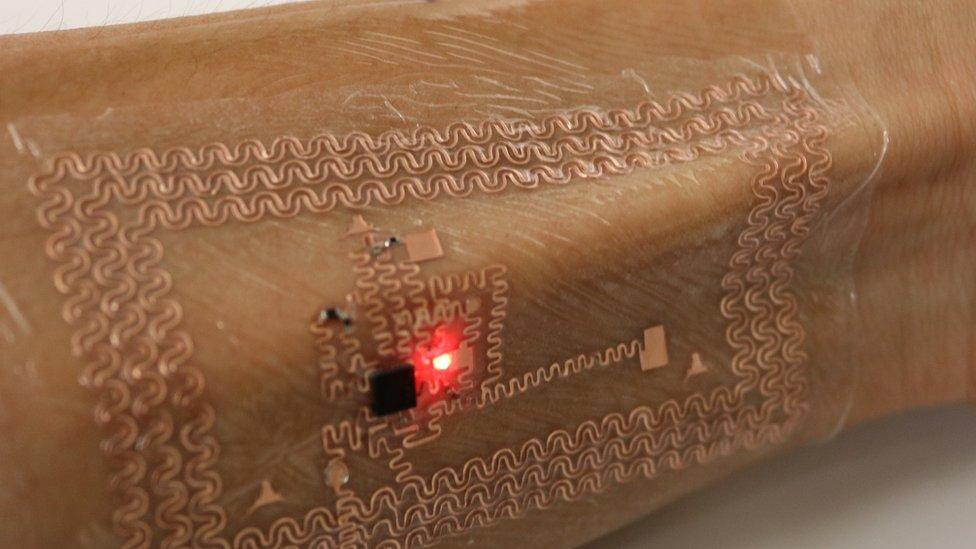

In 2019, Mr Williams and colleagues showed off a different sort of electronic tattoo. Although not embedded beneath the skin, they did demonstrate that it could, external be applied to a flexible part of the body, in this case someone's finger.

The researchers came up with a special ink containing silver nanowires that, once printed onto the body, is both flexible and electrically conductive. They attached a small LED light to the system that lit up when power was applied through the printed material.

At Duke University a team has experimented with a flexible wire that can be printed on the skin

Mr Williams proposes that such technology could be useful for medical purposes but he says that there might be artistic applications as well.

Ms Newell comments on the metallic look of the printed nanowire material used in the prototype.

"I've talked to so many people who wish they could have a metallic, gold-coloured tattoo," she says.

While Ms Newell wonders whether electronics stuck to the surface of someone's skin could ever properly be considered tattoos, she emphasises the creative possibilities that such technology would bring. She imagines creating tattoos that are practically invisible until switched on. That could appeal to people who work in industries where having a tattoo is frowned upon or even prohibited.

Light-emitting tattoos might not only broadcast light outwards to the wearer and other observers. Prof Nanshu Lu at the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues have developed a novel design in which light is shone in the opposite direction. And they can apply this technology in the form of a stretchy, flexible "tattoo" stuck onto the surface of the skin.

Light can be used to measure blood flow and oxygen levels

"Light, depending on the wavelength, is able to permeate through the skin, into the tissue, into the blood vessel," she says.

By measuring the amount of light that reflects back from body tissue, it is possible to calculate the amount of blood flow or the volume of haemoglobin, the protein that transports oxygen in red blood cells.

Oximeters, often attached via a finger clip to hospital patients, including many Covid-19 patients during the pandemic, do the same thing, though they are much more bulky.

Prof Lu and her team have shown that their tattoo-like system can measure blood flow in the fingertips, external and they hope to demonstrate that the same technology could also be used on the neck, head and muscles, with data transferred to a nearby computer via a Bluetooth chip built into the device.

But Prof Lu isn't only interested in medical applications. She suggests that future electronic tattoo designs could light up to reveal when someone's heart is beating faster. That could make dates more interesting.

"You can directly see which gentleman or lady has an increased heartbeat when talking to you," she says, adding that it's something she'd consider using herself.

However, there is also the possibility that electronic tattoos could be used to harvest data about a person, data that could then be transmitted to other devices, sold or hacked, even.

Could technology end up taking over the millennia-old practice of tattooing and detract from its aesthetic value? Ms Newell hopes not.

"At the end of the day, for me, this was always art," she says.