Coffee waste: Companies offer up new solutions

- Published

Could this cup help save the planet?

The UK's caffeine addiction sees us drink around 35 billion cups a year, but that comes at a huge environmental cost.

We throw away more than 2.5 billion disposable coffee cups annually, and around half a million tonnes of ground coffee waste goes to landfill.

The coffee industry also contributes to the UK's carbon emissions, which the government has pledged will be neutral by 2050. Some coffee companies think they have the solutions to help tackle these problems.

You drink your coffee from this cup like a Viking drinking mead from his horn.

Reporter Dougal Shaw drinks from the lidless cup

Called a ButterflyCup, it's 100% paper - there is no plastic coating - and nor is there a lid.

Or rather, you create the lid by doing two simple folds after your drink is poured. It was developed by a pair of entrepreneurs in Ireland.

"We believe it is the world's most environmentally friendly disposable cup," says Tommy McLoughlin, chief executive and founder of ButterflyCup.

From left to right - an early handmade prototype of the ButterflyCup, the finished factory design, and a close-up of the patented internal splash deflectors

It's been a long time in the making, but a previous food business Mr McLoughlin ran helped subsidise a decade-long quest to bring the cup to market. He and business partner Joe Lu finally perfected their product - just as Covid struck.

The pandemic has slowed down take-up of the cup, but it has still been adopted by organisations including the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT), which operates centres across the UK, Columbia University in New York, and Burger King. The fast-food giant is using it in Indonesia for serving ice cream.

A global manufacturer and distributor is also piloting the beverage holder.

The cup works out slightly more expensive than the typical disposable ones containing plastic, says Mr McLoughlin. This may prevent some large chains from adopting it, since they operate very fine profit margins at vast scale.

But the ButterflyCup is cheaper than the compostable ones with separate cup and lids, he says.

Although his product has no plastic lining or lid, there are still some challenges to recycling it.

Its material can be pulped along with things like cardboard, but mainstream recyclers tend only to accept cups when collected separately, citing fear of contaminants.

So even if you put this cup, or similar ones, in the recycle bin, it may end up being rejected at the recycling centre - for now.

However, the cups can also biodegrade naturally, or be composted, says Mr McLoughlin.

Half a million tonnes of waste coffee grounds are thrown away in the UK each year

Many aspects of the coffee industry generate carbon, such as the plastic bags that ground coffee or beans are transported in, as they are typically derived from oil or natural gas.

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of tonnes of used coffee grounds end up in UK landfills each year, generating methane and carbon dioxide.

To meet the carbon neutral target a complete rethink is necessary about how we mass produce consumer products, and deal with them once they are no longer useful.

"It's a kind of 'once-in-a-planet' transition we're looking at, from fossil-based [goods] to sustainable ones," says Rich Riley, co-chief executive of Origin Materials, a US company that specialises in manufacturing carbon neutral materials from waste products.

"But because the market is huge and the need so great, innovation and capital are flowing in to solve these problems."

New Economy is a new series exploring how businesses, trade, economies and working life are changing fast.

In the coffee sector a new crop of companies are experimenting with more sustainable models for consumers.

Ernie, a small business in London, is trying to deal with the issue of the single-use plastic used for transporting coffee in bulk to workplaces.

It uses an electric milk float made in 1963 - also called Ernie. The float delivers coffee from a 30kg carbon-neutral roaster in central London to offices around the capital, using reusable containers made of recyclable plastic. It collects the empty ones to use again, while on its rounds.

The electric float can carry a payload of one tonne of coffee, travelling at 30mph

The business was set up in 2019, and was in a promising pilot phase when the pandemic struck. "We've been massively affected by the lockdowns," says Ernie's business manager Rachel Simpson.

The company reckons before lockdown it could save 4,000 single-use plastic coffee bags and 700 boxes from landfill each month, working with large clients like University College London Hospital and accounting firms Grant Thornton and Deloitte. Large offices would order 100kg of coffee every week, says Ms Simpson.

But with many offices in London still empty, Ernie has had to pivot to delivering direct to individuals working at home. This has kept the firm ticking over, but it can't reduce coffee waste at the same scale, says Ms Simpson.

"We haven't lost hope completely, and believe that people will return to their workplaces," she says. "Absence from the office makes the heart grow fonder."

London-based firm Ernie delivers freshly roasted coffee in reusable canisters

Yet what about the coffee grounds after the drink has been made? Cafes and commercial kitchens produce this soggy waste on a huge scale.

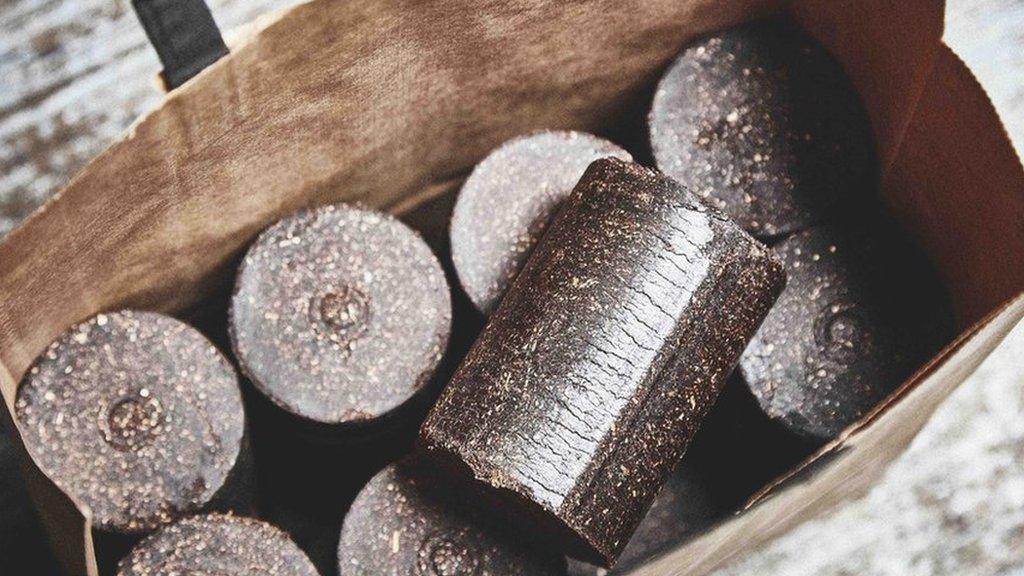

One UK company, bio-bean, is making a profit by turning this into bio-fuel logs for fires.

It collects waste grounds from hundreds of chain cafes, independents and restaurants, by liaising with waste management companies.

These are converted into logs at a factory in Cambridgeshire, where the waste is decontaminated, dried and compressed into cylinders.

The logs are sold at well-known DIY retailers, garden centres and supermarkets as an alternative to wood.

Bio-bean's logs for wood-burning stoves are made from coffee ground waste

Although they still release carbon dioxide into the atmosphere when they burn, the company says this is significantly less environmental impact than if the coffee grounds were left to decompose in landfill.

In fact, old coffee grounds can be used to make a wide variety of objects. Finnish company Rens uses them to make trainers.

Coffee grounds are even now being used to make trainers

The used coffee grounds are processed and mixed with recycled plastic pellets to create a polymer, from which the main skin of the shoe is created. Each pair contains the waste from around 21 cups.

In recent years there has been a big increase in people using coffee-makers at home, like the Nespresso machine, which use single-use pods.

This trend has accelerated in lockdown, with sales of pods going up by nearly 20% in the UK, according to a report by market research firm Mintel.

Originally these pods were made with a combination of plastic and aluminium, making them tricky to recycle - and the used coffee within them would also likely end up in landfill.

However, some companies have now developed compostable pods, which means the pod and coffee together can be sent to food recycling centres.

Companies like Grind now make compostable pods for coffee machines at home

This means decomposition happens in a controlled, industrial setting, and electricity can be generated, creating more of a circular economy.

With sustainable solutions like these companies are trying to make the UK's coffee habit a little greener.

Much will depend on how much consumers want to get on board, but on this some industry players are optimistic.

"It's a massive challenge and a global undertaking," says Rich Riley, "but in our experience customers very much want to embrace the circular economy."

You can follow Dougal on Twitter: @dougalshawbbc, external