How product placements may soon be added to classic films

- Published

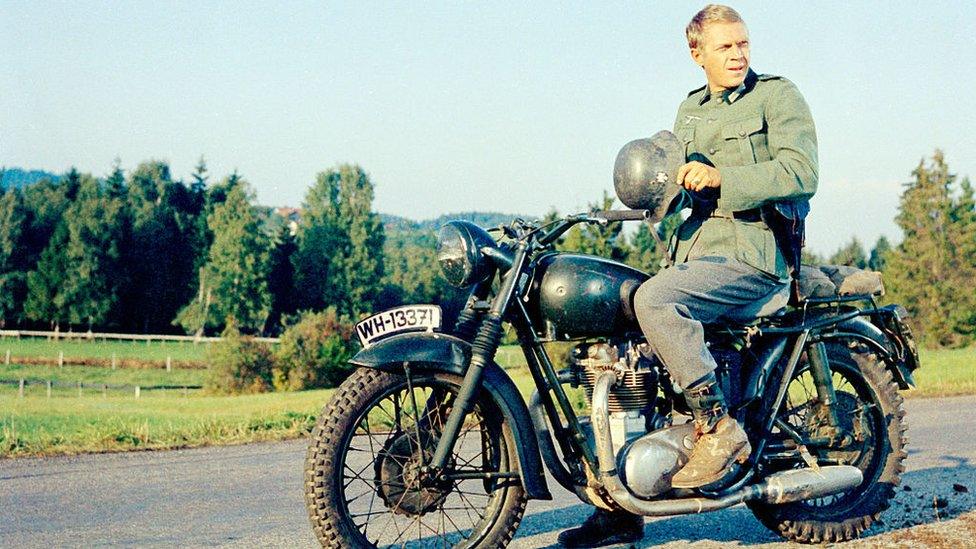

The late Steve McQueen, who gave a memorable performance in the movie The Great Escape, has gone on to advertise a great many things posthumously, since his death in 1980

Product placement is big business for movies and TV series alike, and items can now be added digitally to films and programmes both new and old.

Fans of classic war flicks will know the scene - actor Steve McQueen revs his motorcycle furiously as he is chased by German soldiers.

Hoping to use the bike to jump over a barbed wire border fence, and reach safety in Switzerland, he pauses to gather his thoughts by a barn.

On the side of the building is a big poster advertising a best-selling beer.

You don't remember the billboard advert? Well it might not have been there the last time you watched The Great Escape, but it could well be the next.

Product placement in films is almost as old as the movie industry itself. The first example of the phenomenon is said to be the 1919 Buster Keaton comedy The Garage, which featured the logos of petrol firms and motor oil companies.

Fast-forward to 2019, and the total global product placement industry, across films, TV shows and music videos, was said to be worth $20.6bn (£15bn) that year, according to a report by data analysis firm PQ Media, external. It is highly lucrative to get a show's leading actor to wear a certain item of clothing, or drink a particular coffee, or drive a specific car.

But while previously the product had to actually, physically be there when the shots were filmed, the advertising industry is now turning to technology that can seamlessly insert computer-generated images.

Spot the difference between these two stills from a Chinese TV show. In the above there is no advert in the top left corner

But in this version of the scene, an advert from Coca-Cola has been added digitally

So items can be digitally added to almost any movie or TV show. For example, advertisers could put new labels on the champagne bottles in Rick's Cafe in Casablanca, add different background neon advertising signs to Ocean's 11, or get Charlie Chaplin to promote a fizzy drink.

And then a few weeks, months or years later the added products can be easily switched to different brands.

One of the firms that has developed the ability to do this is UK advertising business Mirriad. Its technology is now being used by a Chinese video streaming website, and the makers of hit US TV show Modern Family have also tried it out.

Mirriad's chief executive Stephan Beringer expects such digital product placement to become widespread. His firm came up with the process after previously making movie special effects.

"We started out working in movies," he says. "Our chief scientist Philip McLauchlan, with his team, came up with the technology that won an Academy Award for the film Black Swan.

"The technology can 'read' an image, it understands the depth, the motion, the fabric, anything. So you can introduce new images that basically the human eye does not realise has been done after the fact, after the production."

Stephan Beringer's firm has developed the technology from its previous work making movie special effects

The technological development comes at a time when product placement is ever more important for advertisers, rising 15% in value globally in 2019, according to the PQ Media report. After all, most of us are increasingly streaming films and TV shows via services such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, which do not have advertisement breaks.

But this high-tech product placement isn't limited to films and TV programmes. The music industry, hit by Covid-19 making touring impossible, and still recovering from the loss of CD sales, is keen to get in on the act.

James Sandom is the managing director of UK-based Red Light Management, which represents musicians and bands including Kaiser Chiefs and Franz Ferdinand.

He believes that many musicians will leap at the chance to add digital product placement to their music videos both new and old. "The opportunity to carve open a new revenue stream is rare, and the ability to retrospectively use existing content and build new content with it in mind is exciting," he says.

So older musical groups could make new money from videos that might be decades old. And current artists who proudly sport the latest trainers, phones or bags, could have them changed a year later to the newest designs, without them having to actually put them on, or re-record a video.

Colombian singer Giovanny Ayala is one of the first artists to use Mirriad's technology, which has enabled him to sign a deal with Mexican brewer Tecate, to have its bottles and logo appear in his music videos.

In this video for Mexican singer Giovanny Ayala cans of beer were added digitally

Mr Beringer says that the next leap forward will be the ability to digitally add product banners to live sports or concert broadcasts "in real time, or milliseconds after".

"There is huge demand for that," he says. "So a penalty or VAR decision in football could see a new advert pop up behind the referee."

Roy Taylor, the chief executive of Californian-based business Ryff, says his firm is taking digital product insertion one stage further.

It has developed the technology whereby the product placement is targeted at individuals, and changes depending on who is watching.

So if you like wine then the hero of a film could be drinking a particular bottle that you might be tempted to try. Or if you are teetotal the star might be sipping on a bottle of branded water.

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Ryff can do this if you are watching a film on a laptop, smartphone or smart TV, by tracking what you previously bought or looked at online. It works in the same way that online adverts pop up on websites based on your past purchasing or viewing history.

"The technology is an attractive bridge between the demand for high-quality content free from intrusive advertising, and alternative sources of content provider revenue," says Mr Taylor.

Cleopatra Veloutsou, professor of brand management at the Adam Smith Business School at Glasgow University, says these technological developments come as movie and TV advertising firms are trying to catch up with their online peers. "They have lost a lot of income, they are trying to find creative ways to catch up," she says.

However, associating your product with a particular film, TV programme or musical artist comes with risk, says Tamsin McLaren, a lecturer in marketing at the University of Bath's School of Management. "Things can go awry if there is a scandal or PR backlash," she says.

Tamsin McLaren says that all forms of product placement come with risk

And film critic Anne Billson cautions that digital product placement raises both legal questions and those of artistic integrity.

"I would be interested in finding out about the legal angle vis-à-vis digital reworking of a copyrighted work, or whether the advertisers would have to buy the film before they tampered with it," she says.

"It also calls into question the role of the production designer, who has put a lot of thought into the look of something, only for some random advertiser to come along at a later date and spoil it with changes or additions that might be anachronistic, or that might not mesh with their other carefully considered design choices."

So to return to Steve McQueen, the so-called "king of cool". While his image is still used to advertise everything from watches to cars, clothes and whisky, retrofitting product placements into his movies would be a step too far for some.