Why video calls might be behind a rise in male cosmetic surgery

- Published

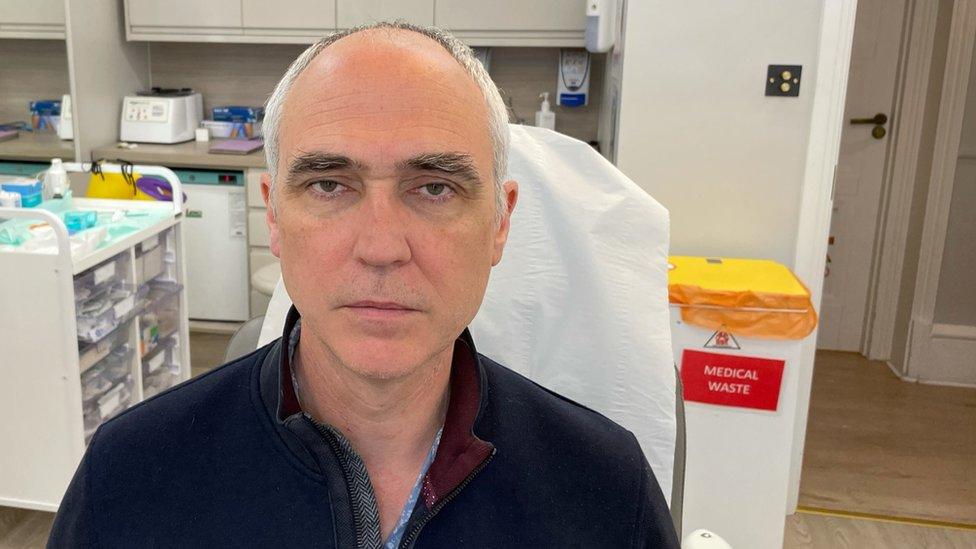

Ed, pictured here before his Botox, says that some of his friends and family were alarmed... while others were jealous

As more men have enquired about cosmetic surgery during the pandemic, BBC reporter Ed Butler decides to brave the Botox needle.

There's an old line that goes "you only get wrinkles where the smiles have been".

Mine though are cropping up in some of the strangest corners of my 54-year-old face.

Applying a surgical remedy hadn't been on my radar until recently, when the past year exposed a possibly surprising rise in men seeking "tweakment".

The British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons says that a third of its members saw an increase in enquiries from men last year, external. Could it be because we have all spent the past year forever seeing our reflection on work video calls?

Has endless video calls over the past year made us worry more about our appearances?

"We know that more and more people have been on social media, and conference calls, because they've been stuck at home," says Dr Helena Lewis-Smith, a psychology researcher specialising in body image at the University of the West of England.

"There's a tool on Zoom, for example, allowing people to smooth their skin's appearance. People who are more likely to press that button during these calls are more likely to be invested in their appearance, and have a worse body image."

The growing trend of male cosmetic surgery is more pronounced in the US, where demand has trebled over the past two decades, external.

"Our society places a premium on youthfulness," says Dr Alan Matarasso, a previous president of the American Association of Plastic Surgeons. "Men are as concerned as anybody else about their appearance.

"And there's been a change in the culture of male preening - it's become socially acceptable for men, whereas before it might not have been so."

The changing patterns of modern work also provides a more hard-nosed business logic, he thinks.

"We're not in a world any more where somebody lives in the same house, or works in the same job, their whole lives," says Dr Matarasso. "And whether you subscribe to this or not, many of us judge people on first impressions."

I hadn't been pressing any image-altering buttons on video calls, but I was curious to see what the fuss was about. I had already discussed my plan with friends and family, whose responses ranged from smirks and alarm, to fascination, and in one case - ill-concealed envy.

Plastic surgery does start to feel like the front-line of an undeclared culture war, with prejudice and shaming liberally dispensed on both sides.

Dr Helena Lewis-Smith worries that the wider beauty industry is 'exploiting people's dissatisfaction'

For those taking the plunge, probably the most popular intervention (for men and women) is Botox. Also known as botulinum toxin, it's the trade name of a protein that in much larger volumes is active in the disease, botulism.

But don't let that necessarily put you off. Applied minimally to your face, it's billed as helping to smooth out wrinkles, such as crow's feet and frown lines, freezing muscles for a period of months at a time.

"We have older successful businessmen, and the owner of a racing car company," says Dr Salinda Johnson, describing some of the clients who visit her London Cosmetic Clinic. "Older men are more concerned about ageing. And we also have younger City workers who want to look more handsome and more attractive."

After a brief consultation, I'm encouraged to lie back on her couch, receive a generous smear of anti-septic across my forehead, and then a series of pin-prick jabs. It's a very fine needle.

I didn't find the injections uncomfortable, although I was warned of possible short-term headaches, and to avoid vigorous exercise over the coming hours. But I'm still debating with myself whether my lines and creases aren't simply an indication of experience or character.

Ed says that the injections were not painful

"There's only so much character we want to have!" argues Dr Matarasso, who says that for many of his male patients, the experience can feel transformative. But he warns he's not in the business of providing eternal youth.

"We're here to make people look as good as they feel. We really can't turn back the clock on a 65-year-old and make them look like they're 25."

Social and the mainstream media are awash with salutary tales about plastic surgery gone wrong. There are no shortage of highly-reputable clinicians offering treatment, but there's also an army of untrained practitioners, particularly in less-regulated countries, drawn by the huge profits to be made in this industry.

New Economy is a new series exploring how businesses, trade, economies and working life are changing fast.

While the risks associated with a Botox injection are low, anyone planning treatment is urged to check thoroughly the qualifications of those providing it, as well as the options for aftercare.

"TV shows and social media are essentially normalising what can be very risky procedures," warns Dr Lewis-Smith. "People do experience some degree of increased happiness and body satisfaction [from cosmetic surgery] short-term, but we don't know how they're going to feel five or 10 years down the line."

She is concerned about the trend among both men and women to place so much effort into perfecting themselves, especially when fashions around appearance and body shape are prone to change.

"Now it's all about the Kardashians, 10 years ago it was Kate Moss," she says. "Think about those people's different body types. Women might now want to have buttock implants, breast implants, lip fillers, but what happens after a few years when we're sold a different ideal?"

Dr Lewis-Smith cautions that while many women currently want to copy the look of the Kardashian family, this might not be the case in a few years time as body and style ideals change

Two weeks after my Botox injections I don't see any big changes in my own appearance, although I do have a general numbness in my forehead. The muscle-freezing will help to inhibit the creation of future wrinkles, I'm told.

Botox is actually more preventative than transformative, and will require another round after three or four months if I'm determined to maintain the effect. This is said to be how many of Hollywood's leading men have held on to their youthful skin for longer than you'd imagine. Although some, like George Clooney, claim not to be tempted.

The global market for cosmetic surgery is expected to be worth $67bn by 2026., external For Dr Lewis-Smith the concern is where this relentless pursuit of cosmetic improvement is leading us.

Ed, pictured here after the injections, says he had a numb forehead for a few weeks afterwards

"We're trying to adapt what we're born with for the beauty industry to make money," she says. "So it does make me scared to be honest.

"We are giving them our money because we want to feel better about ourselves, and to match those ideals with what they show us. They're trading on and exploiting people's dissatisfaction."

You can also listen to Ed Butler's radio report on this story for the BBC World Service's Business Daily radio programme.