Street markets: Can councils get redevelopment right?

- Published

Tracy Taylor who runs Fresh and Fruity greengrocers relies on local produce suppliers

It's lunch time at Preston Market. At one end of the large Victorian market hall, a generous pile of fried egg and chips will leave you with change from a fiver. Two friends have claimed the window seats and grin. "These are ours - we sit here every day."

At the other end of the covered market it's a different crowd and roasted halloumi in a fresh ciabatta will cost you a fraction or so more. A solicitor pops in for a latte: "It's nice to have something here that's modern, it's trendy," he says.

Both locations serve important purposes for local people. Street markets like this one in Lancashire are being revitalised across the country as part of urban regeneration plans.

The decline of British High Streets has put councils under pressure to draw new customers into town centres. However, The National Market Traders Federation says they must not forget their old customers, too.

The trade body wants these upgraded markets to maintain traditional, affordable stalls and produce.

Market traders have strong ties to local community groups

Joe Harrison is chief executive of the NMTF and works alongside county councils and businesses to get the best of both worlds into any redevelopment plans.

"We'll have swanky artisan markets - and that's all that will exist. We need to make sure that we don't take away from people that need access to that affordable food," he says.

Preston's newly glazed market hall is part of a £50m regeneration project. Alongside fruit and vegetable stalls are new coffee shops, mobile phone, and fashion stalls. Outside, traders of all kinds from the old market have new tables to sell their wares, ranging from toys, homemade soaps, and bric-a-brac.

Joe thinks the balance in Preston is right but is appealing to other councils to think carefully about existing customers and traders before they make changes.

Mother and daughter business team, Tracy and Becky Taylor, run Fresh and Fruity greengrocers inside the new trading hall. Their produce is high quality, fresh and popular.

Preston's newly glazed market hall is part of a £50m regeneration project

They agree that selling affordable vegetables is still their staple trade but they've started offering more luxury or exotic items since the refurbishment now that new customers are picking up their shopping in the hall.

They believe they can walk that line because of their connections to local suppliers: "I think a big thing for us is local produce - because we can go straight to the growers and the farmers," says Becky.

But for some it's not so easy. "We've found that a lot of things the markets used to sell, they don't sell anymore, like clothes," adds Tracy.

Their views are supported by a research project, led by associate professor Sara Gonzalez from the University of Leeds, measuring the importance of markets to local communities.

"Markets tend to attract elderly people; people who are from low-income neighbourhoods; those with long-term illnesses, a disability, or people with young children, and migrants or [people from] ethnic minorities," explains Prof Gonzalez.

People who regularly shop at local markets get something else besides their purchases - company, says Prof Gonzalez

"We worry that these more disadvantaged customers will be left aside."

For three years she and her team have analysed indoor and outdoor markets in London, Newcastle and Bury, to learn about the contribution they make to these local community groups.

Their value is not just about good produce at good prices to feed stomachs - it's about regular human contact and interactions that feed the soul.

Prof Gonzalez says that people who shop regularly at local markets get something a supermarket could never give them - company - and that's why many customers make a whole day out of a trip.

"They might have a haircut, they'll have a cup of tea, they'll meet with a friend, they'll do some shopping. And it's weather-proof, it's warm," she says.

Regeneration of older marketplaces is happening across the country

"But more than that, they get to speak to people they don't know. That might be the only people they meet for the whole day, the whole week. So, they actually do develop friendships," says Prof Gonzalez.

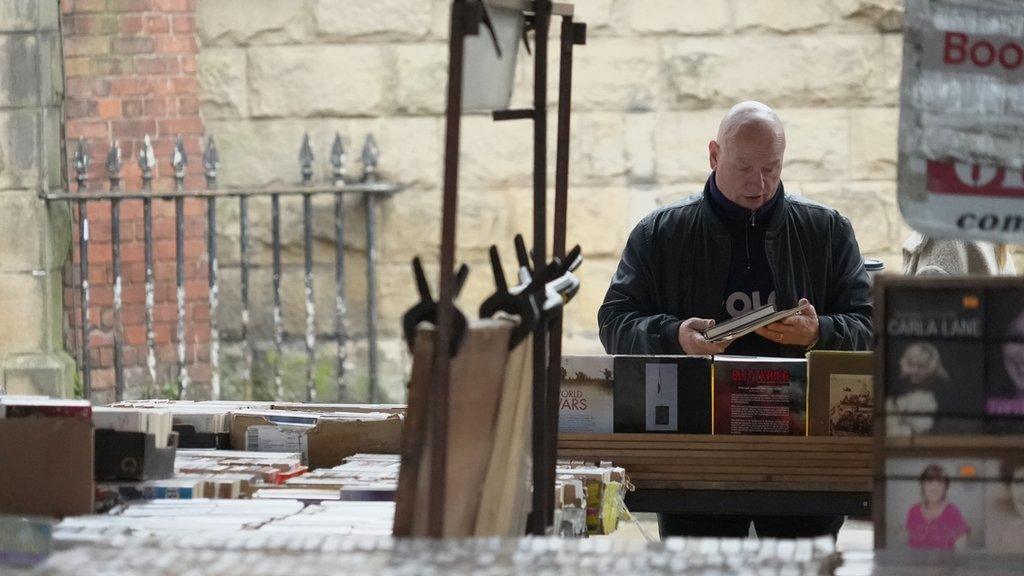

At the height of the pandemic, she spoke to traders in Newcastle's Grainger Market, who had attended a regular customer's funeral. While in Preston, bookstall holder Pete Burns delivered books to regulars he knew relied on the social connection.

"A lot of the die-hard regulars look at you as more of a friend than a trader," he says.

Prof Gonzalez and her team fear these groups are being excluded from council redevelopment plans, because there's no way to measure or make a profit from the valuable sociable interactions markets provide for local communities. Instead, regeneration plans have focused on higher-end, higher-priced offerings.

Citing examples like Borough Market in London or Altrincham Market, that offer late-night fine dining and artisan produce, she explains these can "alienate" many of the vulnerable groups she has worked with.

"We want local authorities to think about the market not as a property asset but as a community asset."