The Amazon sellers who sold up and became millionaires

- Published

Michele Venton sold her Amazon-based business for multiple millions

Becoming a millionaire was never part of the plan. Michele Venton had left London for Bournemouth, keen to escape corporate life - and decided to try selling dresses online.

"I always had this idea that I would design this range of dresses for a particular woman," she says.

She found a factory to make her wrap dresses, and listed them for sale on Amazon, where she was amazed at the amount of interest they attracted.

"I soon worked out that, 'Hang on!' - There was a huge opportunity here," she says.

Clothes, however, were not the easiest product to sell online - too many problems with sizes, too many returns.

Amazon allows third-party sellers to use its formidable distribution network

But as a mother of two, she had experienced more than once the awkward feeling of realising that her children were going to a birthday party in a couple of days, and had no present to give.

She started selling emergency gifts for parents on Amazon.

In less than four years she was doing nearly £10m worth of business every year, across Europe and the US.

But soon the business got too big. Finding millions of pounds to buy all the stock she needed for the rest of the year was getting difficult. "It was going to need somebody with a lot more capital," she says.

So in 2019, when an offer came along to buy entire her business - for multiple millions - she accepted.

Amazon allows other sellers to list their wares on its website, and will even do the delivery or "fulfilment" for them through its formidable logistics network.

The sheer scale of Amazon means that if they get the products and the marketing right, small sellers can find themselves selling huge amounts quite quickly.

With the pandemic forcing many shops to close, many have seen their sales grow to the point where they find it hard to meet all their orders.

Two years ago, when Ms Venton sold up, it was relatively rare to sell businesses based entirely on selling via Amazon.

The buyer, a private individual, insists that we don't name them or their products, for fear of attracting competitors or saboteurs - such is the hypercompetitive world of e-commerce.

But over the past year, a new generation of firms has sprung up to offer Amazon entrepreneurs like Ms Venton a way to sell their businesses.

The biggest and best-known is a US firm called Thrasio, named after an Amazon warrior in Greek mythology. They are buying one to three businesses a week, with around 10 in the UK, and an appetite for more.

Thrasio founder Josh Silberstein says it is now a lot easier for Amazon retailers to sell up

Founded in 2018, it went from nothing to more than $500m (£360m) in revenue in its second year, according to its founder Josh Silberstein.

"Back then [in 2018], it took seven months to sell a company, there were more sellers than buyers, and it was just a gigantic mess. The whole thing was an awful experience for sellers," he says.

Just three years later, there are 64 companies around the world set up to buy Amazon-based businesses, according to the research firm Marketplace Pulse. Together they have raised nearly $6bn since April 2020, it estimated.

In general they look for sellers which have managed to get their heads above the chaotic hubbub of items for sale on Amazon, building up lots of positive customer reviews, and appearing in the first page or two of items that appear in user searches.

Thrasio now owns brands across a wide range of products

The best Amazon sellers make attractive investments because they often have bigger profit margins than their offline competitors, yet still sell for less than their offline counterparts.

The buyout firms hope that by bringing the professional skills and resources of a larger business, they can help the brands grow faster and become even more profitable.

Amazon buyout firms have sprung up in the UK, too, such as Heroes, founded by two identical twins, Riccardo and Alessio Bruni.

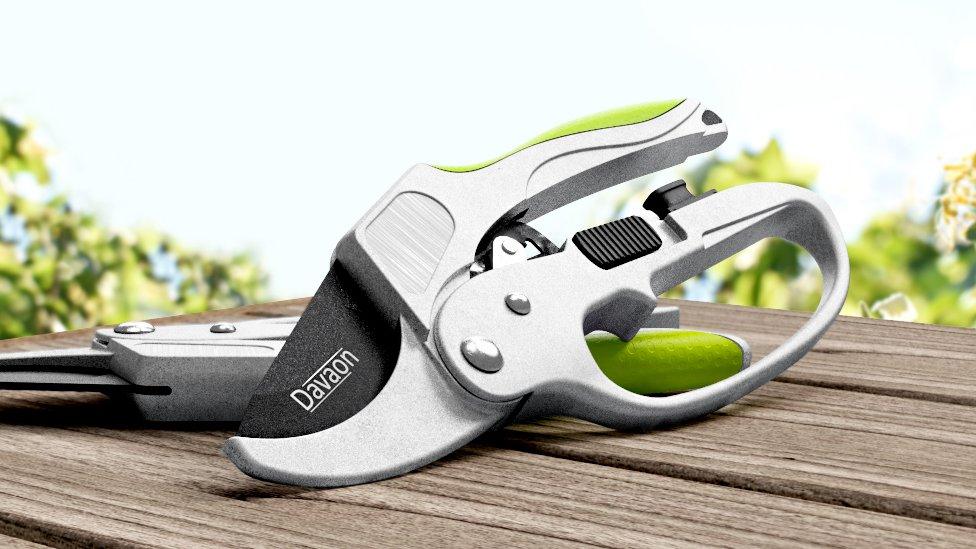

One of their acquisitions was Davaon, a garden tools brand founded by David Stephen. After many years as a travelling salesman, spending long hours in traffic jams and lonely hotel rooms, he was looking for a job that would give him more time with his family.

David and Tracy Stephen plan to start a new company

His wife suggested selling things on Amazon. After a $5,000 course, he found what he felt was an underserved niche - garden tools.

After many hours of trawling through the Chinese website Alibaba to find a supplier, he had a business, a brand, Davaon, and $10,000-worth of secateurs in his garden shed.

Loppers, shears and garden saws soon joined the range, and by 2020 he and his wife were selling more than £2m a year, bought from suppliers in Taiwan whom they still haven't met in person.

But the goal of an easier life was as far away as ever. "It got to the point where we looking at 12 to 15 hours a day. I was doing the weekends, it was non-stop.

The Stephens sold a range of gardening equipment

"If a customer emails on the weekend, you have to answer. I was dealing with stock coming in, we were packing the boxes ourselves, sending them to Amazon. There was never really a break."

He started to receive offers for his business last year. At first he thought they were rival sellers, digging for information.

Eventually, however, Mr Stephen sold to Heroes, partly, he says, because they took the trouble to actually visit him in person at his Northamptonshire home.

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Despite earning enough to retire on, there's something about the thrill of building brands online that makes it hard for entrepreneurs to step away.

Mr Stephen plans to start a new venture soon, and Ms Venton has already launched another Amazon business. It sells "homewares" - but for fear of copycats, that's all she'll say.

The fact that there's an easy way to cash out after a few years is an extra incentive. "This is totally, totally my game plan. I am building this to sell," she says.

But though the potential rewards may be rich, it certainly isn't easy money.

"If you are prepared to have no income for 18 months and work 12-hour days to get this thing off the ground, fine," she says. "There are easier ways to make a buck."