Can old traditions and tech help Singapore reach zero waste?

- Published

Madam Ng has been working as a karang guni for over three decades

You can hear Madam Ng trundling down the road long before you see her.

In the quiet of the early morning, the low rumble of her heavily laden trolley reverberates through the streets of the historic Tiong Bahru area of Singapore.

Madam Ng is a karang guni trader, one of the rag and bone collectors who have traditionally picked up the things people throw away.

This includes everything from old newspapers, drinks cans, second-hand clothes to unwanted electronic devices. They usually sell them on to other karang guni traders or recycling firms.

Karang guni itself comes from the Malay term for the large hessian sacks that they traditionally used to carry their goods.

Karang guni men and women collect the materials thrown away in Singapore

Nowadays, these have been replaced by trolleys like Madam Ng's, often four-wheeled flat-bed carts, or two-wheeled sack trolleys, as well as trucks and vans.

Madam Ng became a karang guni more than three decades ago, as she wanted to make extra money to help pay for one of her daughters to study abroad.

"I was in my 40s and still a nurse. I used to go around collecting newspapers, magazines and books after work - but now I've been doing it daily since I retired," she says as she takes a rare break from her round.

Now, aged 78, her daily work routine would be daunting for many half her age. "Every day I wake up at 4am and am out of the house by 4.30am. I push my cart around the neighbourhood, collecting discarded newspapers and cans. I am out for about four to five hours, then I go home and I'm done for the day."

'Zero waste'

While rag and bone collectors may seem like an echo from the past in many countries, they are still part of Singapore's present and most likely its future.

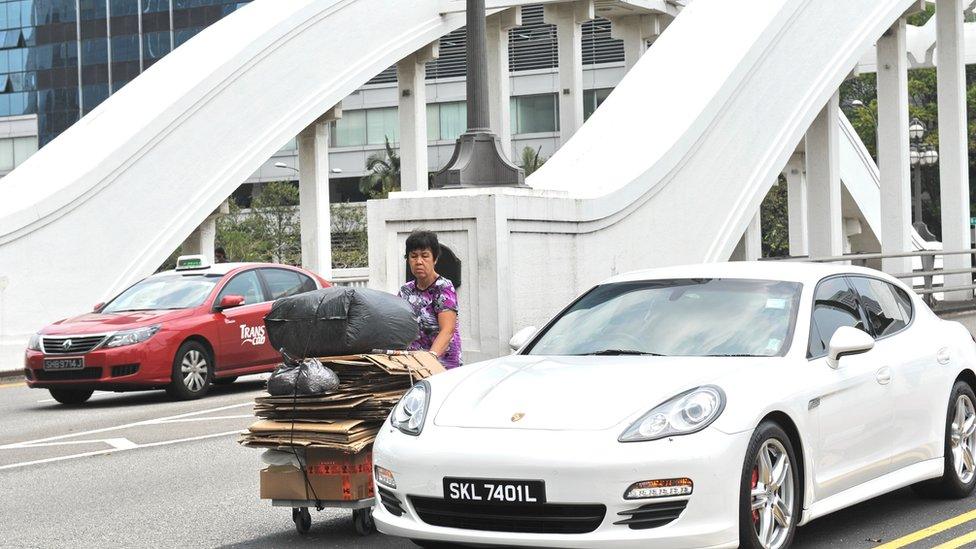

A karang guni woman weaves through heavy traffic with her trolley

Singapore is known as one of the cleanest cities in the world, and its army of collectors are the city-state's original recyclers. Even in this $380bn (£270bn) economy, the government sees them playing a crucial part in its sustainability programme.

The Singapore Green Plan 2030 covers a whole range of sustainable goals, including cutting the amount of waste sent to landfill by 30% within the next decade.

The recycling business was hit hard by the pandemic, as the volume of material Singapore recycled dropped, after the global economy was shut down to slow the spread of Covid.

The sudden halt saw the country's overall recycling rate, for homes and businesses combined, fall to 52% in 2020 compared to 59% the previous year.

Workers sort through waste by hand at one of Singapore's recycling hubs

The National Environment Agency (NEA), which is in charge of Singapore's recycling efforts, thinks that this was just a blip and is now focussed on plans to become a zero-waste economy.

Christopher Tan, director of NEA's sustainability division says he sees karang guni men and women playing a role in the city-state's recycling network as it aims to hit that ambitious zero-waste target.

"They can complement the current collection methods. There's still the challenge of getting the recycling from the door of your home. They have networks. They have knowledge of what can and what cannot be recycled," he says.

Singapore relies on the private sector to manage the island's rubbish collection, waste disposal and recycling services - and it is these firms that are working with the karang guni industry.

Next generation

One such firm is SembWaste. It has created an app - ezi - that helps to connect the karang guni collectors with the company during their working day, as well as members of the public who want recycling collected from outside their homes.

Technology is being used to create waste collection networks

"We have forged partnerships with a network of karang gunis... with more than 100 of them as part of the ezi network," says Goh Siok Ling, SembWaste's commercial director.

At 32, Aiden Ang is part of the new generation of karang guni traders. After graduating with a diploma in telecommunications engineering he chose to follow in his father's footsteps to join the clothing recycling business rather than pursue a more mainstream career.

Despite the downturn in recycling due to Covid, Mr Ang is confident the industry has a promising future: "I personally believe this trade is here to stay in the long term.

"Everyone is getting into the habit of recycling because of education. I am confident the number of recyclers will increase over the years to come."

Mr Ang sees the use of apps as a big step forward, "with young blood in the company we can run the business in a better way, especially with technology". He says this is what helped convince him to enter the trade - and to improve it.

"It is super convenient for the residents interested in participating in the recycling drive. For us as the operator, it helps us to organise the operational flow and handle the transactions very efficiently."

Singapore's Boat Quay district is full of restaurants, bars and cafes which all need waste collection and recycling

Mr Ang also points to opportunities he sees for young people, as the trade is currently dominated by older karang guni collectors, like Madam Ng, many of whom are nearing retirement.

'I want to keep on'

Although Madam Ng may not be part of the new generation of tech-savvy karang guni traders, she is not planning to give up her trolley just yet.

"I sell my collection [on] to another karang guni who comes round on his lorry. He's very busy, as a lot of seniors do what I do, and he collects from them too," she says.

A criticism sometimes levelled at the karang guni business is that it relies on elderly people who are paid poorly for the amount of physical work they put in.

But for Madam Ng the job isn't really about money these days. Since being widowed, she has lived comfortably with one of her daughters and her family.

"It is physically tough. My daughters tell me to stop. But I'd rather do it than sit around at home."

"Sitting too much is bad for you - it's very bad for the mind. When I'm out with my cart, it helps to clear my mind."