Clothes and fuel costs push UK inflation to two-year high

- Published

- comments

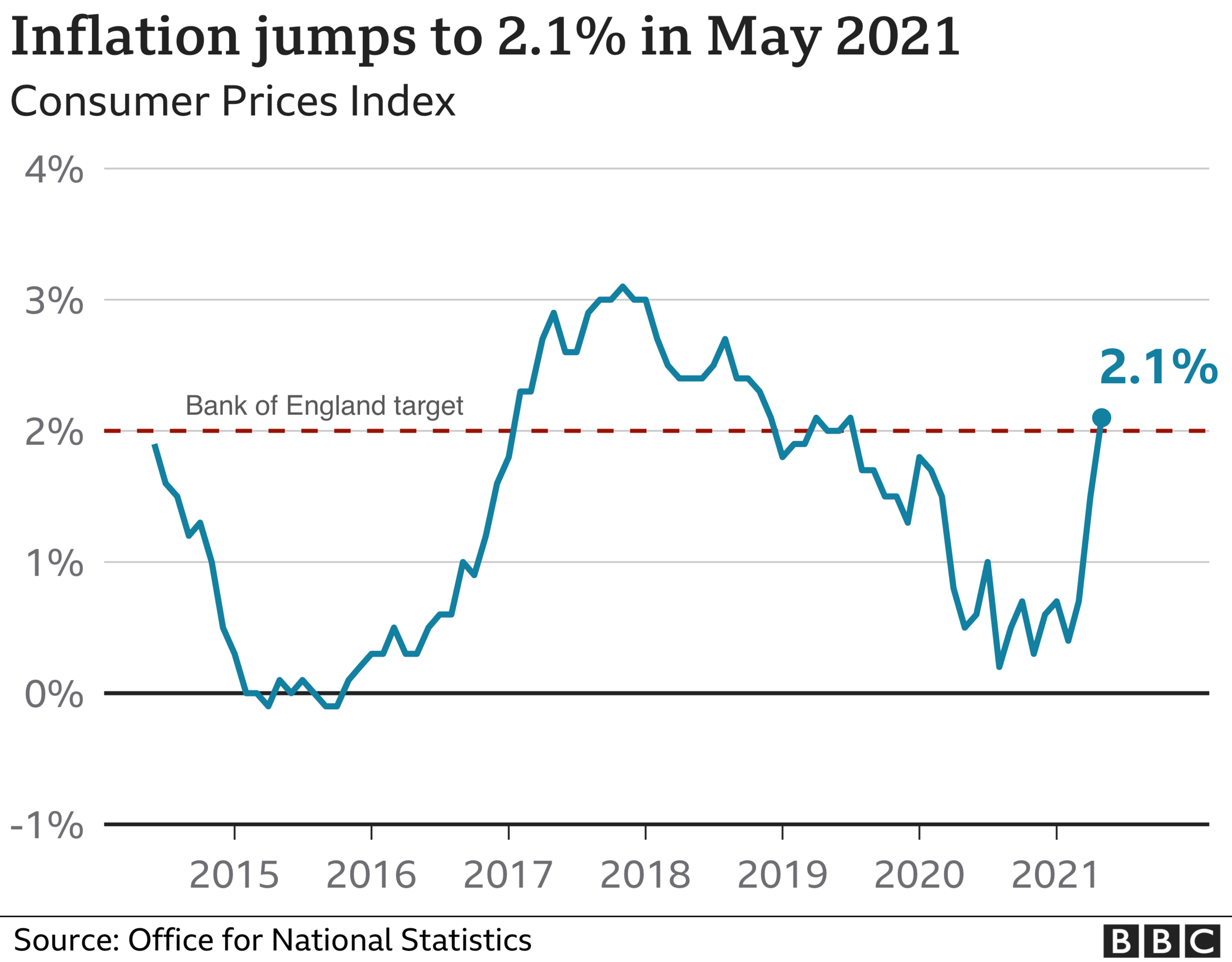

The UK inflation rate jumped to 2.1% in the year to May, the highest for almost two years, as the easing of lockdown sparked a rise in consumer spending.

The Consumer Prices Index measure of inflation rose from 1.5% in April, according to the Office for National Statistics, external, driven by the rising cost of fuel and clothing.

The rate is now above the Bank of England's 2% target for inflation.

That will fuel the debate about whether it's time to raise interest rates.

May's reading was above most economists' forecasts of an increase of about 1.8%.

What is inflation?

Simply put, inflation is the rate at which prices are rising - if the cost of a £1 jar of jam rises by 5p, then jam inflation is 5%.

It applies to services too, like having your nails done or getting your car valeted.

You may not notice low levels of inflation from month to month, but in the long term, these price rises can have a big impact on how much you can buy with your money.

What is driving inflation?

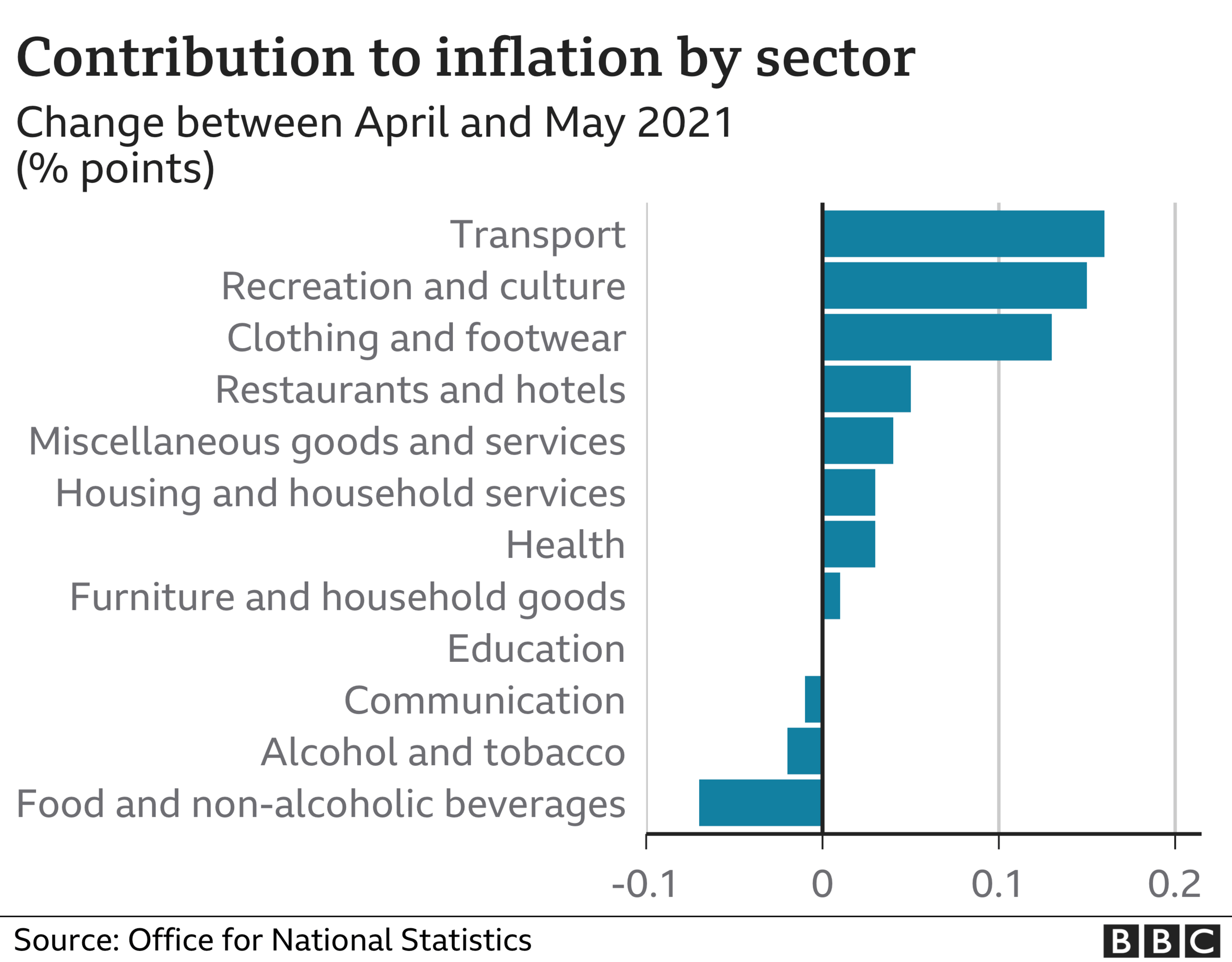

ONS chief economist Grant Fitzner said the biggest single rise was coming from fuel prices, which were falling this time last year as the lockdown started to bite.

Petrol and diesel saw a 17.9% price surge over the past year, representing the highest increase for more than four years.

Crude oil prices have been increasing over the past few months, which is expected to continue feeding through to pump prices.

Clothing prices also increased by 2.3%, the biggest rise since 2018, as retailers significantly reduced their discounting a month after welcoming customers back into stores.

The rise in inflation was, however, partly offset by a negative impact from cheaper food and drink prices. Bread, cereals and meat prices all dipped after seeing significant rises a year earlier.

Karen Ward, a chief market strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management, told the BBC: "Consumers have got all these savings they accumulated last year when they weren't allowed out. But supply is really struggling to keep pace, and so what we are seeing therefore is pops of prices in various aspects of the consumer basket."

Was the jump bigger than expected?

It certainly was. Most economists were expecting inflation to hit 1.8%, and are now suggesting the rate could rise faster and higher over the next few months than previously thought.

JP Morgan's Ms Ward described May's rate as a "big upside surprise".

And HSBC economist Chris Hare said: "Whether the upside news proves temporary or persistent, [May's rate] is clearly a hawkish surprise."

The price data was collected on or around May 11, before pubs and restaurants were allowed to serve customers indoors and cinemas and hotels reopened from 17 May.

The Bank of England has said it expects inflation to hit 2.5% by the end of this year before settling back to its 2% target as the impact of post-lockdown energy price rises fades along with other cost pressures, such as bottlenecks in supply chains.

Does that mean we've nothing to worry about?

As you'd expect, economists are divided.

Ms Ward said that if inflation pressure was sustained into next year, "we could see interest rate hikes" to dampen down rising prices.

UK rates, however, remain at historic lows. Also, there are some benefits to rising rates - for example, on the amount of interest people earn on savings.

Nevertheless, the low-rate environment that has existed for a decade and upward changes could be a shock for many consumers and businesses.

Last week, the Bank of England's chief economist, Andy Haldane, said a rise in inflation above the central bank's target must be only temporary, and that long-term levels of high inflation need to be "avoided at all costs".

Some economists are concerned that despite rising inflation, governments continue to use stimulus to jump-start their post-Covid economies.

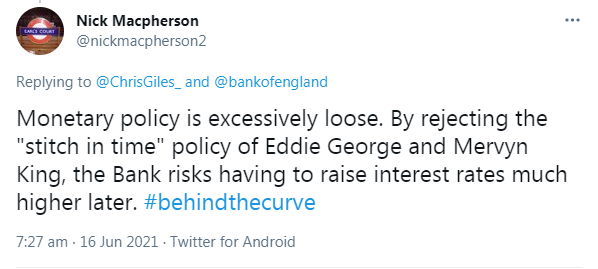

Former treasury official Lord Nick Macpherson tweeted on Wednesday that Bank of England policies to control the amount of money in the economy are "excessively loose".

Lord Macpherson was permanent secretary to three UK chancellors

Is inflation a problem for other countries?

The UK is by no means an isolated case. In the US, where President Joe Biden has proposed a $6 trillion stimulus package, consumer prices hit 5% in May, the highest in almost 13 years.

Jack Leslie, an economist at the Resolution Foundation think tank, said the speeding up of UK price growth from 0.3% last November to 2.1% in May represented the fastest six-month rise since sterling collapsed after the 2008-09 financial crisis.

"But UK inflationary pressures are different - and nowhere as near as large - as those causing fierce debate in the US," he said.

In China, long a source of cheap goods for the world, inflation is also rising - effectively exporting higher prices.

And Eurozone inflation rose to 2% in May, the first time the rate has surpassed the European Central Bank's target in more than two years.

Nevertheless, central banks seems committed to keeping rates low. The US Fed, for example, expects rates to remain close to zero until 2023.

Given the lag between changes in rate policy and the required impact on the economy, some economists worry that central banks could be leaving it too late to change direction.

Why do some experts think rising inflation is a temporary problem?

If you think this morning's higher-than-expected inflation number is something to be scared about, the financial markets don't share your view.

Traders on foreign currency markets, for example, were unimpressed, with the pound shifting up a modest 0.3% against the euro or 0.2% against the dollar.

Inflation may be slightly above the 2% target but it's no higher than it was in July 2019 and well below the 5% inflation of ten years ago, when the global economy was recovering from the 2008 financial crisis.

Part of the reason the markets shrugged off the inflation figure is the widespread belief that the upward pressure on prices is temporary.

Prices of raw materials such as wood and steel have shot up from a combination of two things - demand after economies re-opened and supplies still coming back up on stream. The result? Shortages and price rises.

The confident expectation is that, for example, as steel manufacturers crank up production there'll be more steel to meet demand so its price will fall back, relieving the inflationary pressure.

As summer turns to autumn we'll find out if that expectation is justified.

Related topics

- Published15 June 2021

- Published11 June 2021

- Published19 May 2021