Can Americans pull the plug on petrol-powered cars?

- Published

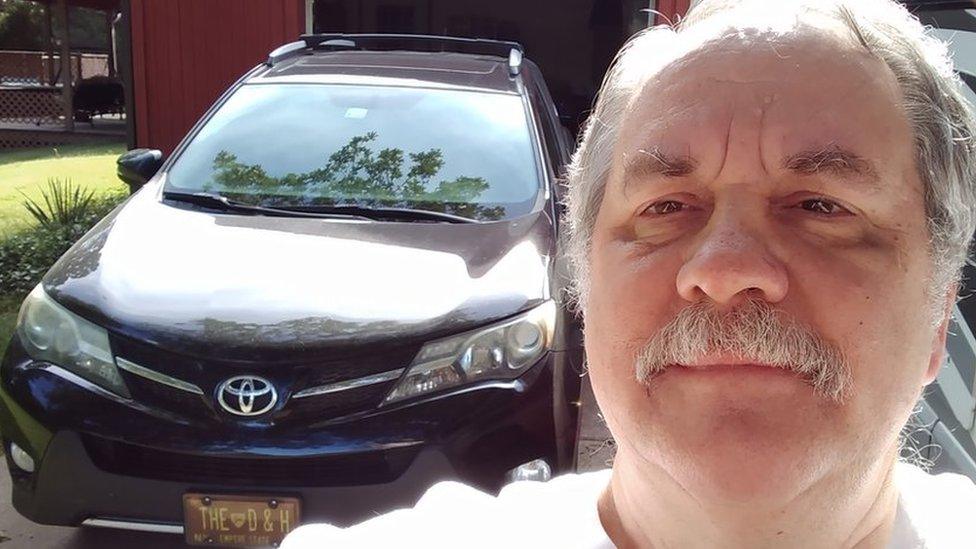

Tom Beckett, who drives a 2013 gasoline-powered Toyota, and has no plans to buy an electric car

US President Joe Biden wants Americans to switch to electric vehicles. Carmakers are on board - but are consumers willing to pull the plug on petrol?

Tom Beckett, a former truck and bus driver, says he's driven at least two million miles in his lifetime, and he is all for burning less gasoline to protect the environment.

But like many Americans, he is "just not ready" to buy a low-emission electric car because of so-called range anxiety - the fear he won't be able to go far enough on a single charge.

The 62-year-old lives in rural Arkansas where he regularly has to drive long distances to get around, and electric vehicle (EV) charging points are few and far between.

"Unless the battery capacity and the range doubles, I don't think electric cars will ever become a big deal in states like this," he tells the BBC.

"People need the confidence to know their cars won't run out of juice. Otherwise they'll just stick with gas."

The US is home to the world's biggest electric car maker Tesla - but demand for EVs in the country remains low

Transport accounted for almost of a third of US emissions in 2019 and the White House has pledged to bring this down. But people like Mr Beckett pose a big challenge to a new administration plan to make zero-emission vehicles account for half of all automobiles sold in the US by 2030.

The goal, which is non-binding, has the backing of major automakers Ford, General Motors and Chrysler-owner Stellantis. Mr Biden has also restored tailpipe emissions rules from the Obama era, weakened under Donald Trump, which will put pressure on car companies to make greener vehicles.

But none of it will make much difference if consumers don't buy in.

Commercial vehicles going electric

'Love of the open road'

Outside of a few major metropolitan areas, EVs still aren't very common in the US and the country accounted for just 2% of new EV sales globally last year, compared to 10% from Europe.

Moreover, while just under half of US adults say they would support a proposal to phase out production of gasoline-powered cars and trucks, a similar proportion would oppose it, according to a Pew Center survey published in June, external.

A major concern about low-emission vehicles is price. Even with federal subsidies, EVs and hybrids tend to cost more than pure petrol cars, even though the vehicles are more economical to run.

"The US has a love affair with cars and the open road," says Prof John Heitmann

However, the bigger issue - in a country that clocks up more miles per driver than almost anywhere else, external - is range.

Currently there are just 100,000 public charging points for plug-in electric vehicles across the US, a third of which are in California - a state that has its own, tougher transport emissions rules.

At the same time, the typical range of a fully electric car before it needs to recharge is 250-300 miles, although it can be as low as 130 miles.

"The US has this love affair with cars and the open road, and there's a great allure in driving long distances," says John Heitmann, professor emeritus of history at Dayton University and an expert in US automotive culture.

"In Europe or Japan you might take the train, but it is very common for Americans drive 1,000 miles or more when they go on vacation or visit the national parks. Electrification has got to fit in around this."

The Biden administration wants to build 500,000 charging points by 2030, and has put aside $7.5bn to fund it in the new infrastructure bill.

But that's half of what the president previously hoped to spend and "falls far short", according to 28 Democrat lawmakers, who say more like $85bn is needed to build out an adequate charging network.

'Consumers will see the benefits'

Yet experts believe the White House's 2030 goal is achievable and that it is only a matter of time before gas-powered vehicles start to be phased out in the US.

Dan Neil, an automotive columnist for the Wall Street Journal, says battery technology is improving fast, prices are falling, and consumers will see the benefits.

"EVs soon will be cheaper to buy and cheaper to operate than gasoline-powered cars," he says. "And as global regulations clamp down on tailpipe emissions, old cars will get less and less satisfying to drive."

Experts believe the price of EVs will come down

He agrees more cash is needed to expand the country's charging infrastructure, but thinks the utilities companies set to profit from electrification will step into the breach. Peer pressure is also likely to play a role.

"People want to buy new models of car and gas powered ones will become unfashionable," he says.

Inevitably, even the US will be dragged along by what happens in the rest of the world, he adds. "The US can't be the only industrial economy to hang on to gas-powered transportation - it wouldn't be economic for the country, it won't be economic for the people who will drive the cars."

Job concerns

Mr Biden has been clear that part of his plan is about ensuring the US car industry does not fall behind in the fast growing global EV market. Stricter rules on tailpipe emissions in the EU are already forcing continental car makers to change their assembly lines, giving them a head start.

"[Joe Biden's plan] is exactly what the whole car industry has been waiting for and now gives them a clear roadmap," says Matthias Schmidt, a European automotive market analyst.

"They can now scale their EV operations safe in the knowledge that those investments will go to cover all three major regions - North America, China and Europe - in a technology where standardisation and economies of scale are key."

Still, Mr Biden could face other obstacles. He hopes to expand subsidies to bring down the costs of EVs for buyers and manufacturers as part of his $3.5 trillion Budget plan, but there's no guarantee it will pass.

The shift to electrification is also likely to cost jobs, given the typical EV requires around three times less manpower to produce.

Dan Ives, an analyst at Wedbush Securities, expects these roles to be replaced in time, but there could be political backlash in states that are home to supply chain jobs, or those that depend on petroleum production such as Texas and Louisiana.

Prof Heitt agrees we could see "big regional impacts" from the transition, but thinks ultimately the economics of electric vehicles will prevail.

"There is always going to be a group of Americans that feel strongly against electric cars," he says. "But there were 17 million horses used for transport in the US around the turn of the 20th Century, and by the 1920s-30s the automobile had taken over.

"The question is, are we going to stick with horses or move on to the next technology?"

- Published5 August 2021

- Published1 June 2021