The Indian women widowed by Covid-19

- Published

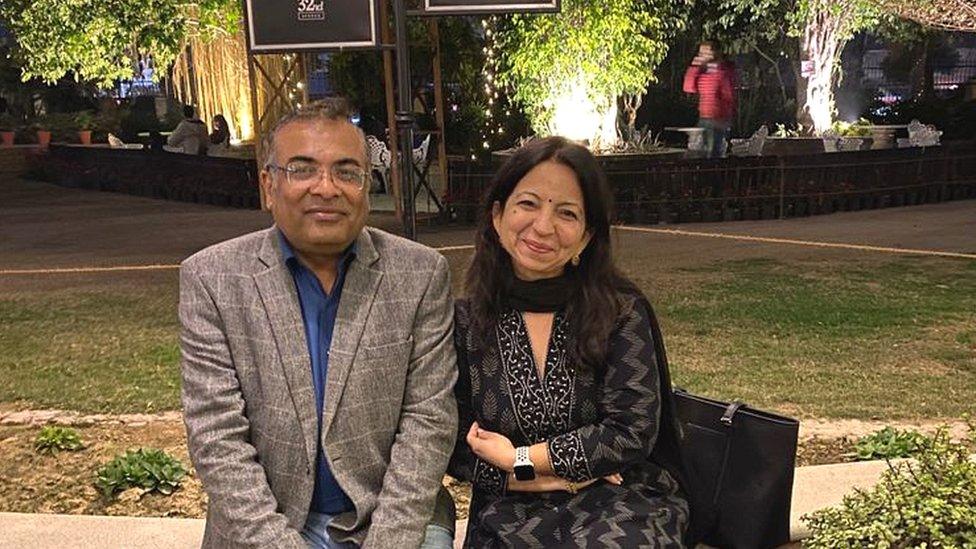

Taruna and her husband, Rajeev. They had been married for 22 years when he died

Taruna Arora lost her husband Rajeev to Covid-19 two days before his 50th birthday.

Rajeev contracted the virus in April, during India's devastating second Covid wave. Medical resources were scarce, hospitals overwhelmed, and his family struggled to get him admitted. They finally found a hospital bed in a makeshift facility set up by the government, but two weeks later he died.

"Rajeev's death is paralysing. These are the worst days of my life, but I have no time to grieve because my life has taken a 360 degree turn," says Taruna, 46. Rajeev, who worked in the telecom sector, was the sole bread winner of the family and took most of the financial decisions. Now Taruna is relying on their savings and her limited knowledge of finances to support their two children.

"We always led a comfortable life and I got everything I asked for. He did all the budgeting and I just asked him for money. Now I don't know how long our savings will last because I've never managed them myself," says Taruna.

She hopes to find a job to support the children but has no work experience and doesn't know where to start. "I just want to find a job, leave the house, meet people and have a cup of tea with someone. When I'm at home the pain won't let me sleep."

Covid has so far killed over 450,000 people in India, according to government figures

India has been one of the world's worst Covid-hit nations, recording more than 450,000 official deaths so far. The pandemic has left tens of thousands of women newly widowed, struggling to adjust to a new life.

Many of these women have never worked in a paying job before. According to the World Bank, India's female labour force participation rate - which was less than 21% in 2019 - is one of the lowest in the world, external.

Many have lost the sole bread winner of their families, and as their worlds changed overnight, they are struggling to manage the double burden of grief and financial difficulties. Gender roles and patriarchal norms at home mean they were financially dependent on their male partners and have been excluded from financial services.

In 2017, Indian women were nearly 13% less likely than men to be able to raise funds in case of an emergency, according to the World Bank. Indian women were also 6% less likely than men to have a bank account, external - a problem that's only made worse by the fact that Indian women are also significantly less likely than men to own a mobile phone or use mobile internet, external.

This makes it harder for women like Taruna to access compensation - such as the recent announcement by the Indian government to pay a sum of 50,000 rupees ($674; £500) to the families of those who died of Covid-19.

During India's second Covid wave, Madhura Dasgupta Sinha, a social entrepreneur in Mumbai, was raising funds for a classmate, a 50-year-old engineer, who was Covid positive and needed critical care. Sadly he died, but the classmates wanted his family to have the funds they had pulled together.

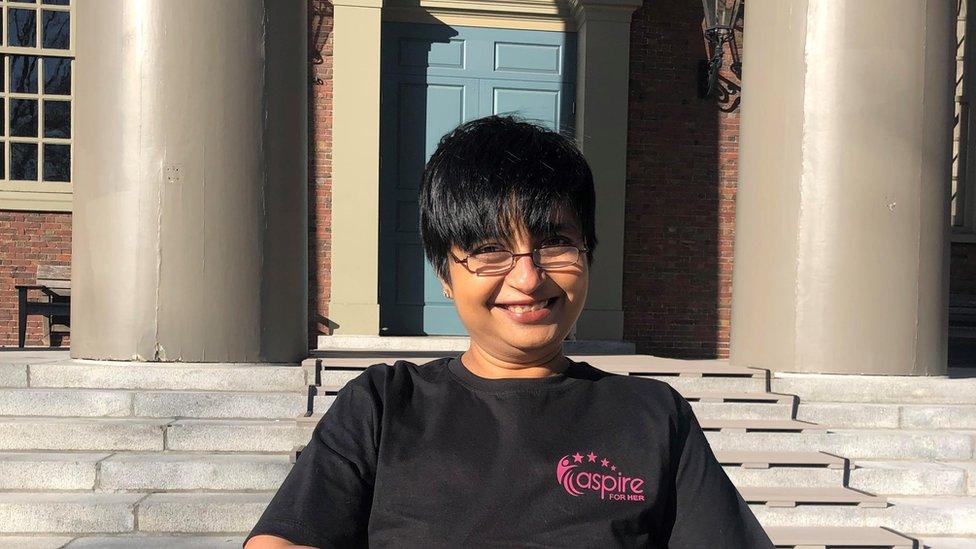

Madhura Dasgupta Sinha is campaigning to help women dealing with life after the death of their husbands

When Madhura asked his wife which account they should credit the funds to, she said she didn't know if she had a bank account. "There was no knowledge in the family on what to do financially when tragedy hits, but this was not the time to teach her internet banking or financial prudence," says Madhura, 51, an ex-banker.

Seeing this, Madhura launched Not Alone, a campaign to help women who had lost the sole bread winners of their families to the pandemic. After the launch, she saw a huge uptick in volunteers from India and the Indian diaspora wanting to help.

There are about 100 women in the community. Many are struggling with their mental health. Madhura and her team of volunteers have seen cases of depression, survivor's guilt, and even suicidal tendencies. Others are struggling to make ends meet.

"Some of these women are facing inheritance issues, for others, the in-laws are not letting them stay on in the marital home. Sometimes the deceased member's workplace makes a generous settlement, but they find they have newfound relatives descending on them," says Madhura.

"Many are struggling to pay their children's school fees. In one case, the person didn't know how insurance works, and she still paid the premium after her husband's death."

In India, 27% of men are financially literate while the figure for women is 20%, says S&P

The root cause, she adds, is poor financial literacy. Globally, 35% of men are financially literate compared to 30% of women, according to a 2015 survey by ratings agency Standard and Poor's (S&P). But in India, financial literacy is lower and the gender gap is wider, external, with 27% of men financially literate compared to 20% of women.

Madhura and her team encourage the women to re-enter the workforce, but some are not ready. For such cases, grief counselling becomes a priority, and the process is not a linear one. Weeks of emotional progress is sometimes set back by a simple trigger that can come in the form of a picture or a snippet of conversation.

Those who are ready are slowly nudged towards employment and are provided with career guidance and support. Many of the women have projects they are passionate about, and the volunteers help grow these into small businesses.

Some start-ups have even approached Madhura saying they actively want to hire from this community, and 12 women have already found their first jobs and others are in the pipeline.

With the right support, Madhura's classmate's wife was able to open a bank account. She received some funds from well-wishers but needed a sustainable source of income. Madhura and her team wanted to help her but hit a roadblock. Even though she was offered a job, her classmate's wife declined, saying she was too emotionally drained. Madhura waited patiently, and finally one day she called back.

"She is now investing wisely, has learnt internet banking and set up remittances for her daughter's education. These are all very small things but to us it's a huge win."