TUC: Jobs at risk if UK fails to hit carbon emissions target

- Published

Up to 660,000 jobs could be at risk if the UK fails to reach its net-zero target as quickly as other nations, the Trades Union Congress (TUC) has warned.

The government has pledged to cut carbon emissions by 78% by 2035.

But the TUC fears many jobs could be moved offshore to countries offering superior green infrastructure and support for decarbonisation.

The union body is calling for an £85bn green recovery package to create 1.2 million green jobs.

TUC research from June shows the UK is currently ranked second last among G7 economies for its investment in green infrastructure and jobs.

However, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) says the TUC's claims are untrue and that it does not recognise their methodology.

The government is currently considering the recommendations of an independent report into the future of green jobs, a BEIS spokeswoman stressed.

"In recent months we've secured record investment in wind power, published a world-leading Hydrogen Strategy, pledged £1bn in funding to support the development of carbon capture and launched a landmark North Sea Transition Deal - the first G7 nation to do so - that will protect our environment, generate huge investment and create and support thousands of jobs," she added.

The TUC says steel industry jobs are at great risk are jobs because their manufacturing process is dependent on burning coal at high temperatures.

Other nations such as Sweden are already bringing to market new technologies that enable steel production without using coal.

SSAB showed off the world's first fossil-free steel plate in August and signed a deal with Mercedes-Benz in September

In August, Hybrit, a joint venture between Swedish firms SSAB, LKAB and Vattenfall, made its first delivery of green steel using hydrogen from the electrolysis of water with renewable electricity, while another firm H2 Green Steel is planning to open a hydrogen plant in 2024.

SSAB has a partnership with Mercedes-Benz to introduce fossil-free steel into vehicle production as soon as possible. The German carmaker wants its entire car fleet to be carbon-neutral across the supply chain by 2039.

The TUC's analysis suggests the jobs at risk include:

26,900 jobs in iron and steel

41,000 jobs in glass and ceramics

63,200 jobs in chemicals

18,000 jobs in textiles

79,000 jobs in rubber and plastics

15,500 jobs in paper, pulp and printing

7,800 jobs in refineries

7,400 jobs in wood products

900 jobs in cement and lime

The UK's green recovery investment is currently a quarter of France, a fifth of Canada, and 6% of the US, it says.

According to TUC general secretary Frances O'Grady, the clock is ticking for the UK: "Thatcher devastated Britain's industrial heartlands with the loss of industry and jobs. Boris Johnson is on the brink of doing more of the same."

She said that unless the government urgently scales up investment in green tech and industry, the UK could risk losing hundreds of thousands of jobs to competing nations.

Industry body the CBI agrees, although it thinks the UK has already "made excellent strides" in cutting emissions from the power sector.

"Now is the time to back up this progress with concrete policies and programmes," said the CBI's decarbonisation director Tom Thackray.

"CBI analysis suggests that spending in areas like electric vehicles and energy efficiency could create 250,000 net new jobs by 2030, but the window of opportunity to realise this is shrinking by the day."

'UK isn't even putting our toe in the water'

Steel plant worker Alan Coombs is concerned that no plans for new green technologies have yet been set out

Alan Coombs, 56, is a Community trade union representative at the Port Talbot steelworks, the UK's largest steel production plant with around 4,000 workers. He has worked at the plant for 40 years.

"Companies overseas are already setting target dates for green steel, but the UK isn't even putting our toe in the water," he told the BBC.

"We've got to have a strategy of what it looks like - how we actually make the steel going forward."

He says he can't see how any firm will be able to deliver new technologies without government support, because it will be expensive.

But most of all he thinks speed is needed: "We need to determine what it looks like for us and get on with it - because, environmentally, I think most every industry realises it's got to change.

"We are not part of the debates, so you can imagine - people are [like], 'Where am I going to be working? What's going to happen to the plant that I work on... and what is the future going to look like?"

'We have to make that adjustment'

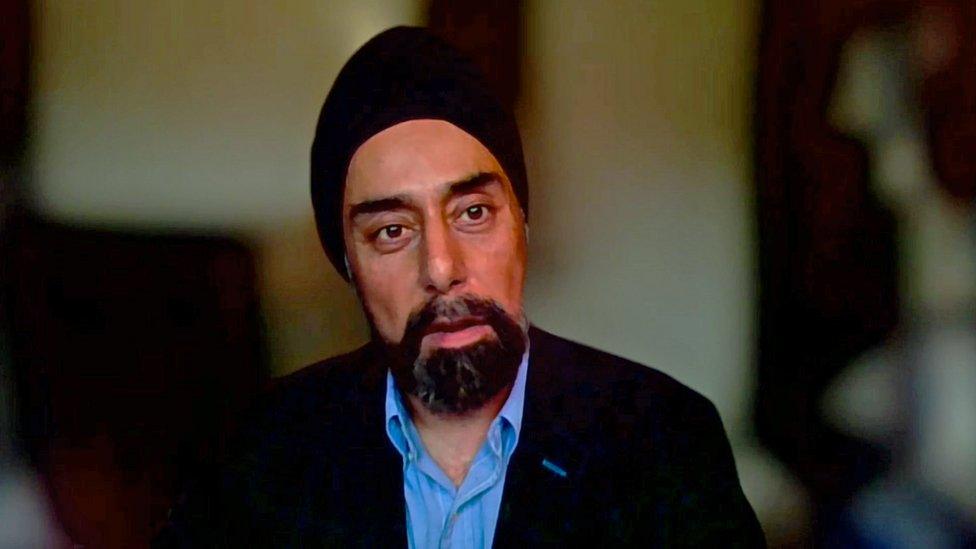

Critiquing the TUC's analysis, Prof Jagjit Chadha, director of the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR), points out that the UK has "made significant progress since 1990" on cutting carbon emissions.

Prof Jagjit Chadha says the government needs to formulate a long-term green economic strategy, together with the private sector

"In the UK, we're almost halfway towards our target, as of last year, in part helped perversely by the Covid crisis," he said.

He is not certain it is possible to tell whether the UK has lost its competitiveness in international trade, particularly since other countries generate more pollution than us.

He also says that only "a very small fraction of people" - 2-3% of the labour force - is directly affected by the UK falling behind other nations in net-zero targets.

But he sees it as inevitable that all industries will eventually have to go green and he wants government plans "that promote the rotation of the economy away from one that's emitting carbon emissions to one which isn't."

When the UK was part of the EU, it was given about £7bn from the European Investment Bank per annum, which then led to £20bn in investment a year - the government will need to find investment to replace that.

"If we think about that happening over the next 10 years, we're then talking about public and private investment public together, probably in the region of £200bn," he said.

Unions and bosses aren't always on the same page, but when it comes to carving out a green future, they are broadly at one.

Revolutions are rarely bloodless. The transition to a net-zero economy will inevitably have some impact on traditional jobs, especially in polluting industries. That's spelt out in the government's Green Jobs Taskforce report, external from July.

So it's a delicate time. The extent of the impact will depend on the policy decisions we make now and whether sectors like the steel industry can be persuaded that there is a tasty enough "carrot" to go green, in the form of incentivising demand for a greener product perhaps or extra funding.

And whether the "stick" - in the form of any policy to push firms to net-zero - won't be used too aggressively.

It's a difficult path for the government to tread. The UK has a legally binding commitment to reduce pollution by 2050.

However this will come at a massive financial cost, at a time when the pandemic has left the UK with high levels of public debt.

With all that in mind, the government will set out more information on how the move to net-zero will happen and how it will be paid for, in its Net Zero Strategy, launched ahead of the COP26 summit at the end of October.

- Published20 April 2021

- Published14 July 2021

- Published24 June 2021