CEO Secrets: 'In my business, you eat what you kill'

- Published

WATCH: Riki Bleau reveals the adage he lives by at work

Record label boss, Riki Bleau, has helped to discover some of the biggest names in UK hip hop and grime. He explains how he rose through the ranks from selling CDs on the street, for our business advice series CEO Secrets.

The offices of his Since '93 record label, which occupy part of Sony's London headquarters, are decorated with a symbolic wall of vinyl.

There are fifteen albums on the wall, all released in 1993. The records are mainly hip hop artists like Cypress Hill and Wu-Tang Clan, but Radiohead's Pablo Honey also makes the list.

Bleau has a symbolic wall at his label's office, with a nod to his childhood

"You see I was 14 years-old in 1993", explains Riki Bleau, surveying the wall. "I think that's the age at which you start to choose your own identity, and in part you do it through music." That's why he called the record label he co-founded with Glyn Aikins, Since '93.

Riki Bleau is a rarity: a UK record label boss who is black. Yet the genre he specialises in - grime and hip hop - is populated by predominantly black artists. He's helped to turn this into a UK success story exported around the world.

He's been instrumental in discovering artists like Emeli Sande and Sam Smith. He's also signed the likes of Naughty Boy, Labrinth and Krept & Konan.

You can spot the stars who stay grounded in spite of their newfound fame, he says. "They don't treat you 'brand new'." Those people are often the ones who end up having long careers.

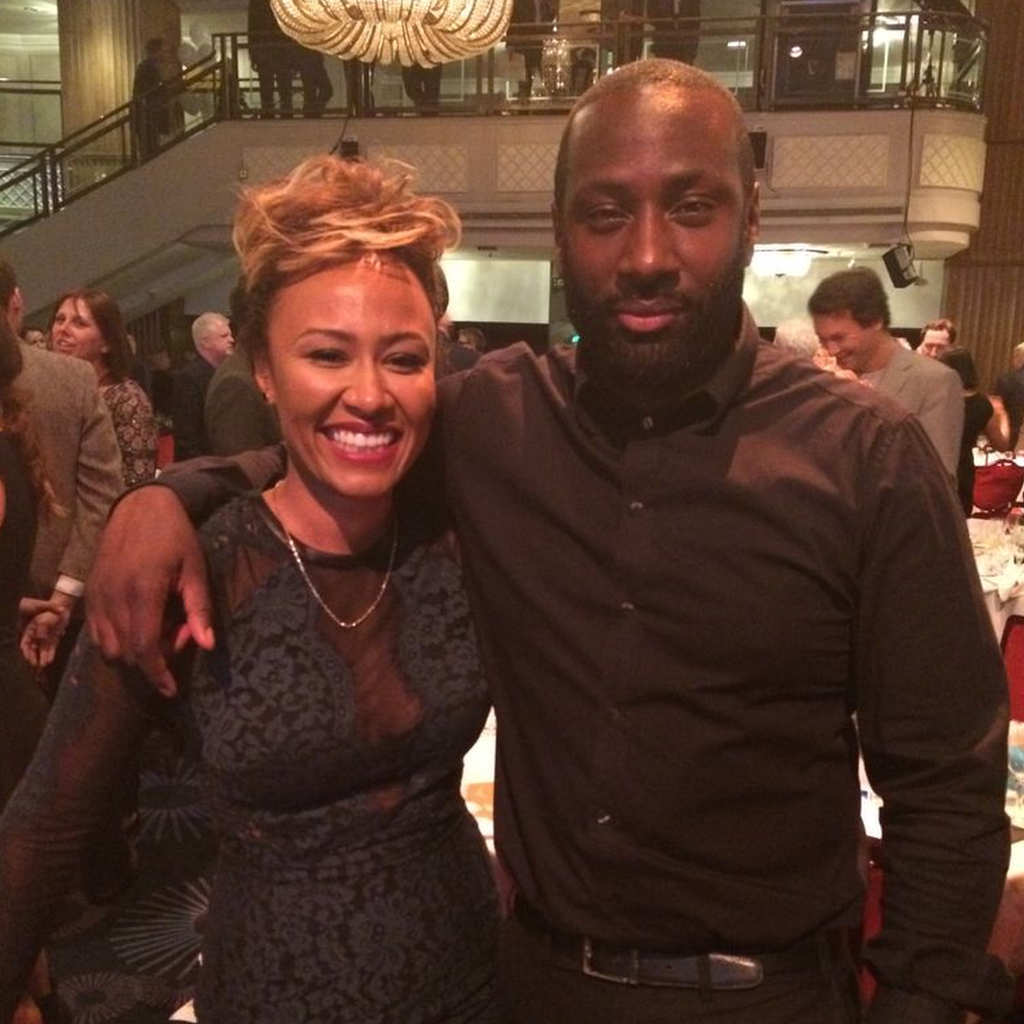

Emeli Sande at an awards ceremony with Riki Bleau

Bleau himself started out dreaming of being a hip hop star.

When he was in his teens, in Hackney, east London, he was part of a four-person rap crew.

The group had a manager but no record deal, so they created their own label and sold self-printed CDs at London underground stations, hassling passers-by to listen to their tunes.

"Our first print run was 2000 CDs," Bleau remembers. "We each had to sell 400. Nobody wanted to be the one who couldn't sell their CDs. Our whole ethos was, we'll do it like Avon. I'll give ten to a cousin, another ten to a friend. You sell them for a fiver and give me £2.50."

They also did what they called "the 32-borough tour." They sold at all London's markets and tube station exits.

Bleau was amazed to discover he was the best at selling the albums.

Eventually Bleau's group sold 10,000 copies of their debut release. But looking back on it, he realises this experience benefited him in another way. He was also networking - and for someone without any contacts in the music industry, this was invaluable.

He met the founders of Channel U while selling his CDs on the streets. Channel U was a dedicated music station available on satellite TV - before YouTube came along, it was the place where hip hop and grime bands could get their break.

Bleau helped Channel U find video content and up-and-coming musicians. It was awkward to do this while still trying to promote his own group, so he became the group's manager, moving over to the business side.

Does he ever regret giving up being an artist?

"I haven't picked up pen and paper since and if I was a true creative, I would have struggled to let go," says Bleau. "I'm quite a practical person. I was probably always built for business, I just didn't know it."

However, looking back, there were some clear signs.

"While my friends played StreetFighter, I played Tetris. I've got a problem-solving mentality, and that's why I enjoy business."

He continued to show a flair for the business side of music and went on to become a manager at the Channel U station. By the mid-2000s it had become an important showcase for black culture and in particular grime music.

Bleau moved into a new world where he was attending industry showcase events and rubbing shoulders with A&R executives and Radio 1 DJs.

Bleau manages Krept & Konan

"This was my introduction to what I now call 'the real music industry'", says Bleau. It was an education for him in concepts he hadn't understood before, like music publishing and royalty deals.

He met music executive Tim Blacksmith, who explained the publishing business model. "It's funny, before that, I thought of a white guy with long hair busking as a songwriter," remembers Bleau. It hadn't occurred to him that black artists he knew like Wiley or Tinchy Stryder could be considered as songwriters, as well as performers - and make money this way.

Bleau's first big signing was Labrinth, who he met at a mentoring event he had organised at a Hackney Youth club.

Labrinth had been working as a music teacher and Bleau helped him find huge success with hits like 'Let the Sun Shine'. Labrinth also helped to write hits for the likes of Tinie (known as Tinie Tempah until 2020).

Bleau again showed his flair for talent-spotting by discovering Naughty Boy on MySpace, an artist he still manages today. He went to visit him at his parent's home in Watford and listened to some tracks he'd made with his friend - Emeli Sande.

Bleau manages Naughty Boy, who worked with Emeli Sande

He built up a stable of songwriters who could write material for others as well as perform themselves.

Bleau signed up the publishing rights and helped them strike deals with record labels. Every time their music was played, he would get a cut.

Through the rich network of contacts he'd built up grafting his way through the music industry, from the bottom up, he had developed a knack of knowing the next big thing - or person.

For example, Bleau signed Sam Smith, when the future global star was still paying the bills as a barman.

Bleau's life became a whirlwind of Mobo, Brit and Ivor Novello award parties.

After finding success with songwriters, the next logical step was to create his own record label. He set up Since '93 Records in 2018 with business partner Glyn Aikins, an A&R executive at Virgin Records, who made his name discovering So Solid Crew and Craig David. The label is part of the Sony Music Group.

The pair are now signing acts to build up the label's identity further, which they want to be broader than just hip hop.

Bleau says he couldn't have planned anything strategically in his career and each stage has just been the solution to the problem that preceded it - like a game of Tetris.

Glyn Aikins, Loski, Morrisson, Aitch, Fredo and Riki Bleau at an awards show

The music industry is predominantly a white, male space and Bleau says he has occasionally faced micro-aggressions and slights, which he wouldn't have encountered if he was a typical white, middle-aged music executive.

"At first I was very cautious about how I presented myself because I felt people would judge me if I had a head full of dreadlocks, or my jeans were a bit too low."

He felt pressure to be less authentic and stand out less to make people around him feel more comfortable. This is a shame, he thinks, because in fact appearance has nothing to do with ability.

Looking back on his career so far, he has benefited from several black mentors, like Tim Blacksmith. These connections gave him confidence, says Bleau.

"As a young guy in Hackney growing up I didn't know what a music label executive was.

"I was brought up to believe I had to work two times as hard [to get an opportunity] - that was a given. After everything that's happened in 2020 with George Floyd, I don't want future children growing up to think that way."

"There is a lot of black talent [in the music industry], but not black executives. When we started the label, me and Glyn were the first of our kind.

Darcus Beese, who used to be president of Island Records, was the only black president of a record label in this country.

But our success has encouraged other labels to need a version of us, to invest in other black executives."

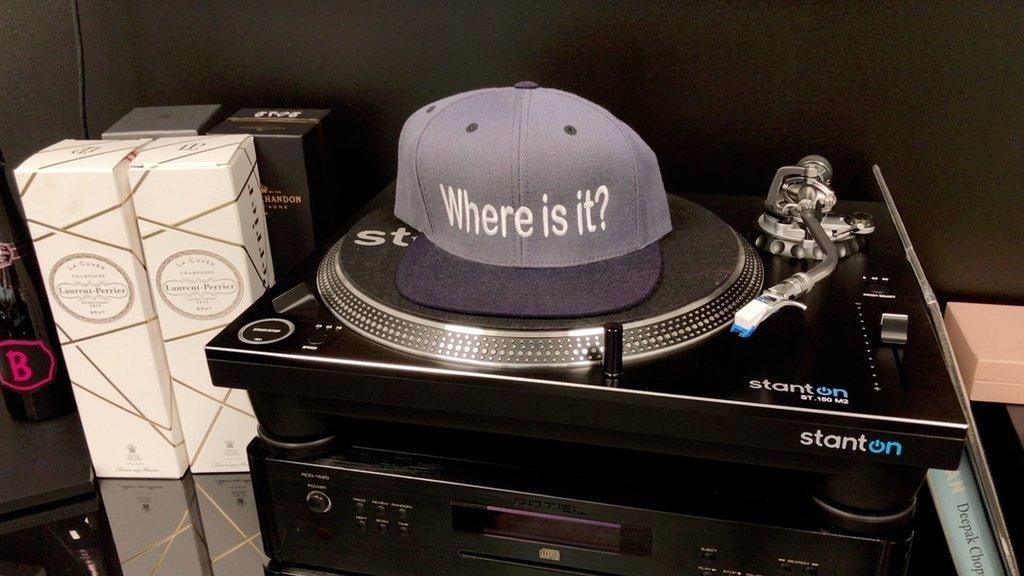

Bleau says he lives by an adage, printed on this cap

Bleau describes himself as a "hunter gatherer" in the music industry.

"I eat what I kill, which in this business is the next talent I find."

There's no excuses, you have to deliver that next artist and that hit record, he explains. It's all about "the deliverable", he says, the same as in any other business - the same lesson he learned on the streets.

If that sounds brutal, it can be a great leveller too, he adds.

If you are the one to find the next Sam Smith, Emeli Sande, Ed Sheeran or Michael Jackson, then nobody cares about the colour of your skin.

"That's one of the great beauties and equalisers of the music industry. The level of talent you work with is the barometer of what you can achieve."

You can follow our business reporter Dougal on Twitter: @dougalshawbbc, external