Changing China: How Xi's 'common prosperity' may impact the world

- Published

China says its policies aimed at narrowing the widening wealth gap are precisely what it needs in this moment of its economic trajectory - but critics say it comes with even greater control of how business and society will be governed.

And while this "common prosperity" drive is squarely focused on people inside the country it has the potential to have huge repercussions for the rest of the world.

One of the most visible consequences of common prosperity has been the refocusing of corporate China's priorities to the domestic market.

Technology giant Alibaba, which in recent years has seen its global profile rise, has now committed $15.5bn (£11.4bn) to help promote common prosperity initiatives in China, and set up a dedicated task force, spearheaded by its boss Daniel Zhang.

The firm says it is a beneficiary of the country's economic progress, and that "if society is doing well and the economy is doing well, then Alibaba will do well".

Rival tech giant Tencent is pitching too. It has pledged $7.75bn to the cause.

Alibaba boss Daniel Zhang speaking during the launch ceremony of the Alibaba Rural Vitalization Fund

China Inc. is keen to show it is playing ball with the Party's mandate - but when the push towards more companies publicly backing Xi Jinping's new vision first started, it did come as a "bit of a shock", one major Chinese company told me privately.

"But then we got quite used to the idea. It's not about robbing the rich. It's about restructuring society, and building up the middle class. And we are a consumption business at the end of the day - so it's good for us."

Luxury sector may lose out

If common prosperity means an increased focus on the emerging Chinese middle class - then that could mean it is a boon for global businesses catering to these customers.

"We can see that the focus on young people getting jobs is good," Joerg Wuttke, president of the EU Chamber of Commerce in China, told me.

"If they feel they are part of social mobility in this country, which has been eroding, then it is good for us. Because when the middle class grows, then there is more opportunity."

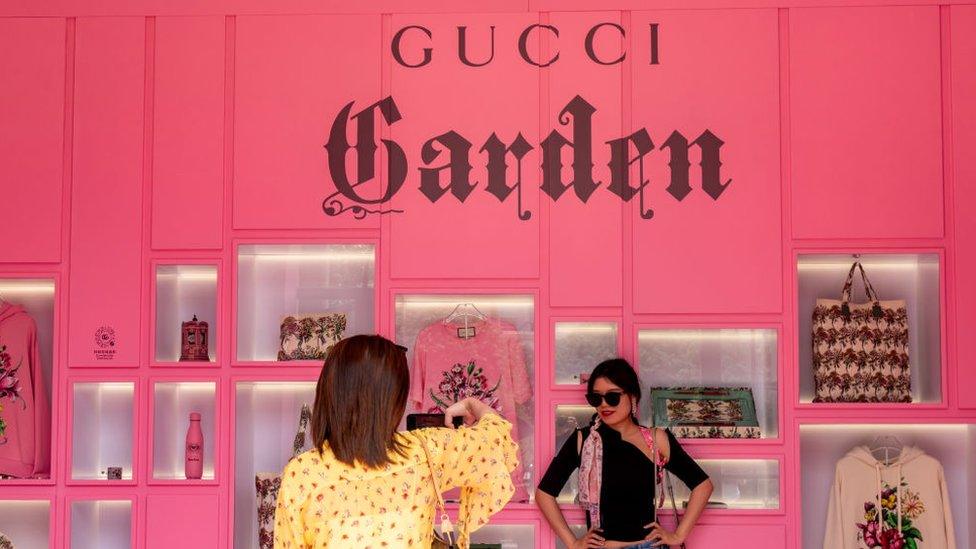

The growing Chinese middle class has boosted spending on luxury goods

However, businesses that are tied to the luxury sector may not do as well, Mr Wuttke warns.

"Chinese spending accounts for about 50% of luxury consumption globally - and if China's rich decide to buy less Swiss watches, Italian ties and European luxury cars then this industry will take a hit."

But while Mr Wuttke acknowledges China's economy does need critical reforms to increase the amount an average Chinese person earns, he says common prosperity may not be the most efficient way to get there.

Why does China’s economy matter to you?

Steven Lynch of the British Chamber of Commerce in China also says common prosperity is not a guarantee that the middle class will grow in the same way it has in the last forty years.

He likes to tell a story about how quickly the Chinese economy has expanded over the last few decades.

"Thirty years ago a Chinese family could have a bowl of dumplings once a month," he told me on the phone from Beijing. "Twenty years ago, perhaps they could have a bowl once a week. Ten years ago - that changed to everyday. Now: they can buy a car."

But so far Mr Lynch says, common prosperity hasn't resulted in anything concrete, besides the sorts of corporate social responsibility efforts that Alibaba and Tencent have adopted.

"There are also a lot of instant regulations sprung on a lot of sectors," he said of the recent crackdown on technology companies. "That causes uncertainty - and raises questions. If they are turning more inward - then do they really need the rest of the world?"

The 'new socialism'

At its heart common prosperity is about making Chinese society more equitable, at least according to the Communist Party. And this has the potential to transform what socialism means in the global context.

"The Party is now concerned about average workers - like taxi drivers, migrant workers and delivery boys," says Wang Huiyao of the Centre for China and Globalisation from Beijing.

"China wants to avoid the polarised society that some Western countries have, which we have seen leads to deglobalisation and nationalisation."

But long time China-observers say that if transforming socialism - with Chinese characteristics - into an alternative model for the rest of us is really what the Party wants, then common prosperity is not the way.

"It is part of the leftward lurch and part of the lurch towards ever more control that has been indicative of Xi Jinping's tenure," says George Magnus, associate at the China Centre at Oxford University.

Mr Magnus adds that common prosperity does not mean replicating a European style social welfare model.

"The implicit pressure is to comply with the Party's goals," he says. "There will be tax on high and 'unreasonable' incomes, and pressure on private firms to donate to Party economic objectives," he says, "but no big move towards progressive taxation".

A top down Utopian China

It is clear that common prosperity is a major part of how the Chinese state and society will be governed under Xi Jinping.

With this comes the promise of a more equitable society - a bigger and wealthier middle class, and companies that give back rather than just take.

A sort of top down Utopian China, that the Party is hoping will prove to be a viable alternative model for the world to what the West has on offer.

But it does come with a catch: even more control and power in the hands of the Party.

China has always been a difficult environment for foreign businesses to operate in, common prosperity means that the world's second largest economy just got even more difficult to navigate.

This is the third in a three-part series looking at China's changing role in the world.

Parts one and two explored the background to Xi Jinping's transformation of the Chinese economy and how Beijing is rewriting the rules of doing business.

Related topics

- Published30 September 2021

- Published29 September 2021

- Published24 September 2021