Will the government's economic plan work?

- Published

Rising prices and flat productivity are two of the challenges facing the government

The UK is facing two supply shocks right now.

One is a global supply shock as the world's economy sluggishly wakes up from lockdown.

It shows itself in backed up cargo ships from China in California's seas, unable to offload their cargo; in thousands of cars left without microchips; in rising natural gas prices.

On top of that there is a UK-specific supply shock.

Inflation pressures

This comes from fewer European workers, and the imposition of non tariff barriers on trade with the rest of Europe.

Both these shocks are pushing up general prices. The global shock is the dominant factor right now, but in some sectors such as pig farming, and into the future, the UK-specific supply crunch may matter more.

The PM has sewn together several acute economic phenomena and sought to explain them in one sweeping narrative: that constrained supply of foreign workers will help raise wages for Britons.

Driver shortages that were only a month ago denied as having any relation to post-Brexit policy, are now embraced as the very point of EU exit.

Indeed, the shortages at petrol stations and on some shop shelves are seen as being part of a transition to a new post-Brexit high-tech and high-wage economy.

The Prime Minister is right to argue that these are problems we may have wished for given the situation a year ago.

They are problems of surging demand, and normalisation of demand in the economy.

That was far from certain a year ago, amid fears of lockdowns causing a depression and mass unemployment.

But while we have reported on rising wages in sectors where there are shortages, this is yet to filter into the overall figures for earnings in the economy.

Wage rises

Some annual earnings figures are up by extraordinary amounts, but that is the consequence of distortions in the statistics from lockdown and furlough.

The same distortions led to the suspension of the triple lock for pensions.

Up to a point it is good news for those with skills in hot demand.

But the wage rises are not the result of increases in productivity. They are the consequence of those two significant supply shocks.

There are fewer workers as a result of a combination of Covid and Brexit.

And there are severe post-pandemic logistical crises and backlogs affecting the world, most clearly the microchip shortage in the car industry.

Costs are going up for the same amount of production.

The trade-off between economic growth and inflation is getting worse.

In simple terms, if this is right, the wage rises seen in certain occupations will be gobbled up by rising prices across the economy.

Robots

The answer, says the government, is for businesses to invest in the workforce with training and skills to raise productivity to match wage rises.

A ready pool of workers from EU, up until this year, decreased the incentive for such investment.

The Chancellor's "super deduction" tax cut provides an additional huge incentive for businesses to invest in new machinery to improve productivity.

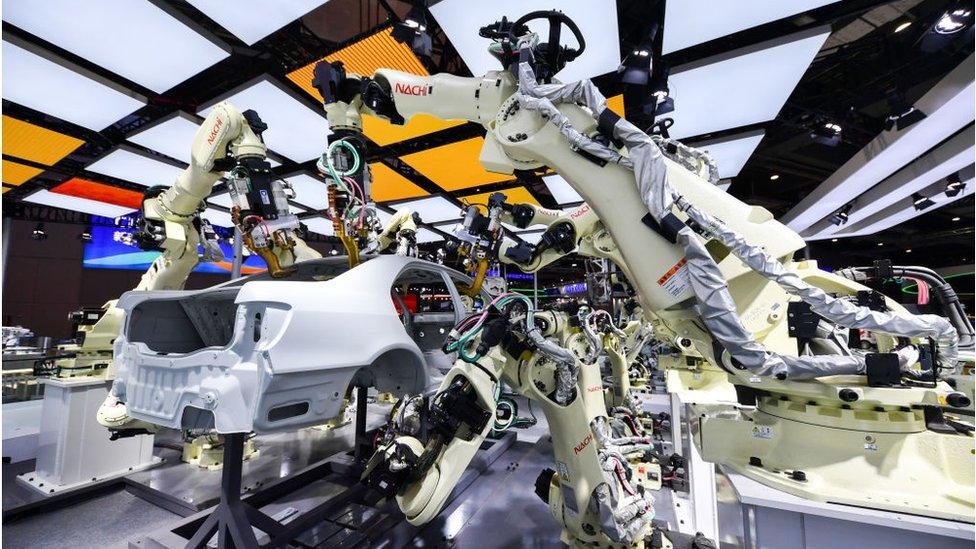

The UK is far behind Japan and other countries in 'robot density'

The UK, for example, does not even appear on league tables of industrial "robot density", having less than a third of the number of robots per 10,000 employees of Germany, Sweden and Japan, and a tenth of Singapore's number. So there is room for significant improvement.

But that still leaves a considerable timing gap.

Consumer prices are going up now. In a best case scenario the productivity enhancement to match them will take years.

But more than that, in many manufacturing industries the super deduction investment is far more likely to involve automation of jobs previously done by EU agency workers, than their replacement by retrained British workers.

Consumer hit

The other challenge for the government is that inflationary pressures cannot really be naturally contained by forcing the private sector to increase wages.

There are numerous examples of bin collectors or bus drivers being sucked into the freight industry, given the wage rises.

But then where are the bus drivers and bin collectors then going to come from?

The local providers of public services will also have to raise their wages, which will hit prices or council tax and business rates.

Can a more general public service pay freeze survive a structural rise in inflation?

Throw in an imminent judgment on the rise in the National Living Wage, and it is difficult to see how consumers don't end up footing a larger bill for these wage rises.

And then there is a very significant concern that Number 10 may well be underplaying.

Rate rise pressure

An independent Bank of England needs to be able to smash incipient inflationary pressure with a great big mallet.

The Bank has been traditionally willing to look through one-off spikes in energy prices, or currency falls, or the impact of the post-pandemic rebound: that is, to avoid interest rate rises at times of high inflation.

But the government is leaning into the post-Brexit supply shock to wages.

It is, in some part, the author of this additional labour supply shock, which makes the economy more inflationary.

If it can make a definitive judgement that this is indeed the case, then the Bank will raise interest rates more quickly, and possibly by more than otherwise.

Both it and the OBR are currently assessing the impact of these factors.

So there are significant challenges to the government's new economic strategy.

Clearly it is not just about economics.

The "positive" supply shock from British firms having access to an unlimited pool of east-European workers had social and political consequences, which helped bring about Brexit and the Prime Minister to power.

But the neat narrative that current stresses and strains are all part of a transition plan is risky.

It makes the Bank of England's waiting game more difficult.

And well before the fruits of high investment, technology and wages emerge, it stands to be tested by the immediate reality of rising prices, and perhaps by international markets too.

Related topics

- Published3 October 2021