Why the vending machine is making a comeback

- Published

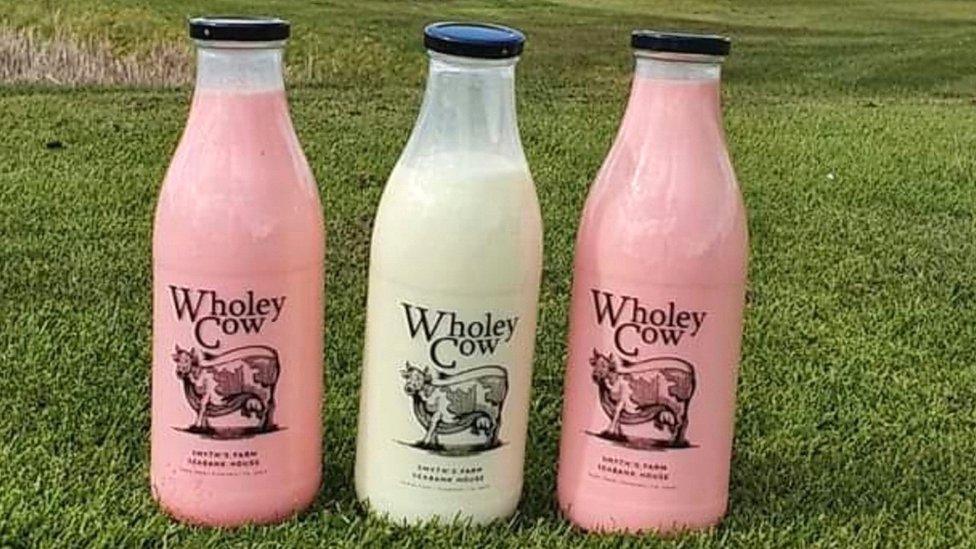

Wholey Cow sells flavoured milk from a vending machine in County Louth, Ireland

"It was something new, something different," says Tomás Smyth, without whom Ireland would not have received its first milk vending machine.

Mr Smyth's Milk Shack sells his Wholey Cow brand of milk in half-litre and litre recyclable glass bottles.

The adventurous can select from twelve different flavours, from chocolate to banana and salted caramel.

The vending machine opened for business amid a lockdown, at the end of March.

"For two months it was crazy, 80 to 90 people in a queue here every day," says Mr Smyth, a dairy farmer in Ireland's County Louth who has 180 cows with his two brothers.

He says his customers like a local product, with fewer transport miles and which is never more than a day old.

"We have a lot of different farmers across the country, coming to chat and see our set-up," he says. Dairy farmers in Offaly, Meath, and Donegal have now visited and followed suit.

The pasteurisation equipment was supplied by Unison Process Solutions and the vending machine was supplied by Italian firm DF Italia and cost between €50,000-60,000 (£43,000-51,000).

Vending fresh products requires more expensive machines

Mr Smyth joins a growing body of small business owners who are giving new life to the old business of vending machines, amid Covid and challenges to traditional High Street retailing.

Traditional machines serving offices, schools, and hospitals saw their business evaporate as workers, students and visitors stayed at home.

In the UK, of the 24,500 employees servicing these machines, some 5,000 were made redundant. But innovative and niche machines, often boasting upmarket, healthier and specialist products, tell a different story.

David Llewellyn, chief executive of the Vending and Automated Retail Association, says automated micro markets saw 367% growth last year. These are small convenience stores, without staff and where customers pay using a smartphone app or at an unattended till.

Meanwhile sales of healthy snacks (less than 5% fat and 0.2 grams of salt) grew by 147% from vending machine in the last year, he says.

And the vending options are always expanding. For example, you can now purchase fake eyelashes from a machine (at Lash Loft in Newcastle) and perfume (from Russia's Perfumatic) and even collect your prescriptions.

An automated pharmacy can give pharmacists more time for customers

Enrico Donà sells prescription vending machines at Pharmaself24 in Vicenza, Italy. He says that matching a prepared prescription with the customer is a straightforward job which a machine can do quite easily.

He argues the machine gives pharmacists more time to dedicate to customers who need more help.

During Covid, demand for Mr Donà's automated machines for collecting prescriptions surged.

Pharmacists see the machine, which takes three to four hours to install, as "an extra employee".

For patients, instead of waiting in queues and worrying about opening hours, "you get there, you enter a pin code and you collect. There it is, easy," Mr Donà says.

Rome's university district has a pizza vending machine

In April, Rome got its first automated pizza vending machine - on the Via Catania near La Sapienza university district.

The red contraption cooks and dispenses pizzas in three minutes, ranging from margherita to diavola, for between €4.50-6 (£3.80-5.10).

Italy has one vending machine for every 145 people, lagging only Germany for vending machines' popularity in Europe.

Both countries though trail Japan, with one machine for every 25 people. "They have no vandalism," notes Mr Llewellyn ruefully.

One big change has been the way vending machines accept payment, says Mr Llewellyn. Today in Britain 47% of machines offer cashless payment, double the proportion of a year ago.

And vending machines are increasingly smart devices, which communicate with central management systems.

So before route operators leave a depot, they know what has to go into every machine.

Until recently, it was a question of "it's Tuesday, so we go here," Mr Llewellyn says.

Some products are more suited to vending for others. For something like perfume, which can be distributed in a concentrated form and then reconstituted in the machine, you can save many travel miles and packaging, points out Manish Shah, chief executive of UK unattended retail company Aeguana.

Andrea Goswell, commercial director at vending machine manufacturer Westomatic, points out that many of us carry around reusable water bottles.

Dispensing drinks into those cuts down on plastic waste, she says.

You don't have to press buttons anymore - you can just hover

Its "Hydration Station" lets you refill your own bottle with triple-filtered chilled juices, and is operated by hovering over a button - you don't even need to press.

The industry's biggest challenge has been changing the refrigerating gas away from R134-a, previously the most common refrigerant. R-134a is a significant greenhouse gas - one gram has the same warming potential in the atmosphere as 1,410 grams of carbon dioxide.

Vending machine makers have been moving to use carbon dioxide instead. Ironically it is a greener refrigerant, though it operates at pressures five times higher than the gas in the older systems. "That conversion has been quite hard work," says Ms Goswell.

The pandemic and race to sustainability are changing the vending machines we see everywhere, argues Mr Donà.

"There are a number of challenges, and the solutions are not so easy to find. But our technology can bring benefits and change what we're doing in a much better way."