The tax fraud merry-go-round that cost billions

- Published

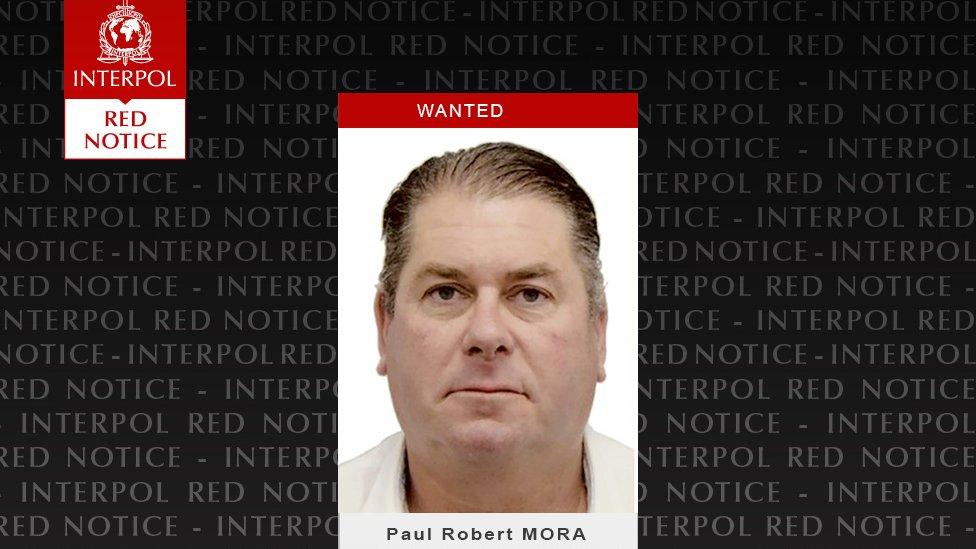

His face stares out from "wanted" posters at airports and railway stations across Germany: a stocky middle-aged man with a ruddy face and slicked-back hair.

But this man is no gangster or armed robber. In fact, he is a former banker. His name is Paul Mora and he is wanted on suspicion of tax fraud.

Earlier this year, Mr Mora became the subject of an Interpol Red Notice, a request to law enforcement agencies around the world to locate and arrest him.

He has not been tried or convicted of any crime. Nonetheless, he has become - in the most literal sense - a poster boy for a scandal described in the European media as "the theft of the century".

The so-called "cum-ex" affair involved US pension funds, German banks, London-based investment bankers, international lawyers and many others.

It focused on huge share trades which were carried out with the sole purpose of generating multiple refunds of a tax that had only been paid once.

It is believed to have cost European governments billions, while many of the trades were orchestrated from London.

The scandal first came to light in 2018, but further details are now emerging thanks to a joint investigation by media organisations around the world, coordinated by the German not-for-profit newsroom, Correctiv.

The investigation has been named The CumEx Files 2.0.

Exploiting delays

Cum-ex trades involved the sale of shares from one investor to another immediately before the payment of a dividend to shareholders (cum, or with, dividend), while they were delivered after the dividend date (ex-dividend).

This was done to exploit delays in the settlement process and create confusion over who actually owned the shares at the time the dividend was paid. It enabled both parties to claim refunds of withholding tax - even though the tax itself, charged on the dividend at source, would only have been paid once.

In order to maximise the potential gains, elaborate structures were built which allowed huge quantities of shares, often borrowed, to be passed in a circular manner between a number of different parties. The structures were designed to remove market risk and to disguise what was going on.

The scam began to gather momentum in Germany in the early years of the century, until the authorities there clamped down on the practice.

It later spread to other jurisdictions, notably Denmark. Both countries are now actively pursuing those involved, putting the role played by the City of London under the spotlight.

Last year, Martin S and Nicholas D, two former London-based employees of Germany's HypoVereinsbank who can't be named fully for legal reasons, were handed suspended jail sentences after being found guilty of tax evasion in the first trial to focus on the legality of cum-ex trades.

Martin S was also ordered to pay back €14m he personally made from the transactions. The convictions of both men were upheld by Germany's highest court, the Federal Court of Justice, in July.

Their sentences might have been greater, had they not been helping prosecutors with a raft of detail about cum-ex deals, helping to feed a growing web of inquiries.

More than 1,000 individuals are currently under investigation. Documents made public during the trial show that banks such as Barclays and Santander are under scrutiny, along with high-profile US financial giants and a large number of German institutions.

Santander says it is co-operating fully with the relevant authorities. Barclays declined to comment.

Driving force

"This certainly wasn't just a German problem," confirms one insider, who took his concerns about cum-ex trading to the authorities.

"Germany was obviously a key target. But the mind and the driving force was clearly in London. It was a London-orchestrated fraud, managed by US funds."

Paul Mora was Martin S' boss at HypoVereinsbank. He later went on to manage his own investment vehicles, Ballance Capital and Arunvill.

He has been widely portrayed as one of the first to see the money-making potential of cum-ex.

Now living in his native New Zealand, there seems little prospect of his agreeing to face prosecution in Germany, however.

Sources close to Mr Mora say he has no confidence he would be given a fair trial.

He rejects the suggestion that he was "some sort of architect of cum-ex", and believes himself to have been vilified for carrying out trades which he did not believe were illegal at the time.

Nor is Mr Mora the only prominent target for prosecutors in Europe. Another to have gained notoriety is Sanjay Shah, whose London-based hedge fund Solo Capital was heavily involved in cum-ex trades.

He currently lives in Dubai, on the Palm Islands. When his business was thriving, he amassed significant wealth, building a property empire.

He became renowned for throwing extravagant parties, while celebrities such as Prince agreed to perform at concerts for an autism charity he founded.

But now much of his fortune is frozen, the result of legal action by Denmark's tax authority, SKAT. It claims that Solo Capital and a number of other institutions were responsible for siphoning off a total of £1.5bn in public money.

Policing the system

An attempt to recover the funds through the High Court in London failed earlier this year, however, when a judge ruled that the case could not be heard in the English Courts. That decision is likely to be appealed.

Meanwhile, Mr Shah insists the Danish authorities' actions against him are politically motivated.

"My aim is just to make as much money as I can," he told German broadcaster ARD's Panorama programme.

"When when I started off, I didn't think for a minute that anything was illegal or criminal. I didn't want to put myself in danger of going to prison," he added.

'I'm not worried about going on trial, because I believe that I didn't do anything wrong."

But according to Richard Collier, a tax expert and author of Banking on Failure, which analyses cum-ex, it is wrong to focus too heavily on individuals.

"It doesn't answer why this happens," he explains. "Why we have scandals like cum-ex, like Libor, like the global financial crisis."

"The reason all this keeps happening is because we've created a system that we can't police. We've got a much bigger systemic problem than we have a problem of greedy bankers."

Related topics

- Published21 October 2021