Bank of England hints at future interest rate rise

- Published

- comments

The Bank of England has signalled it will raise interest rates in "coming months" in response to high inflation, but held off on an immediate increase.

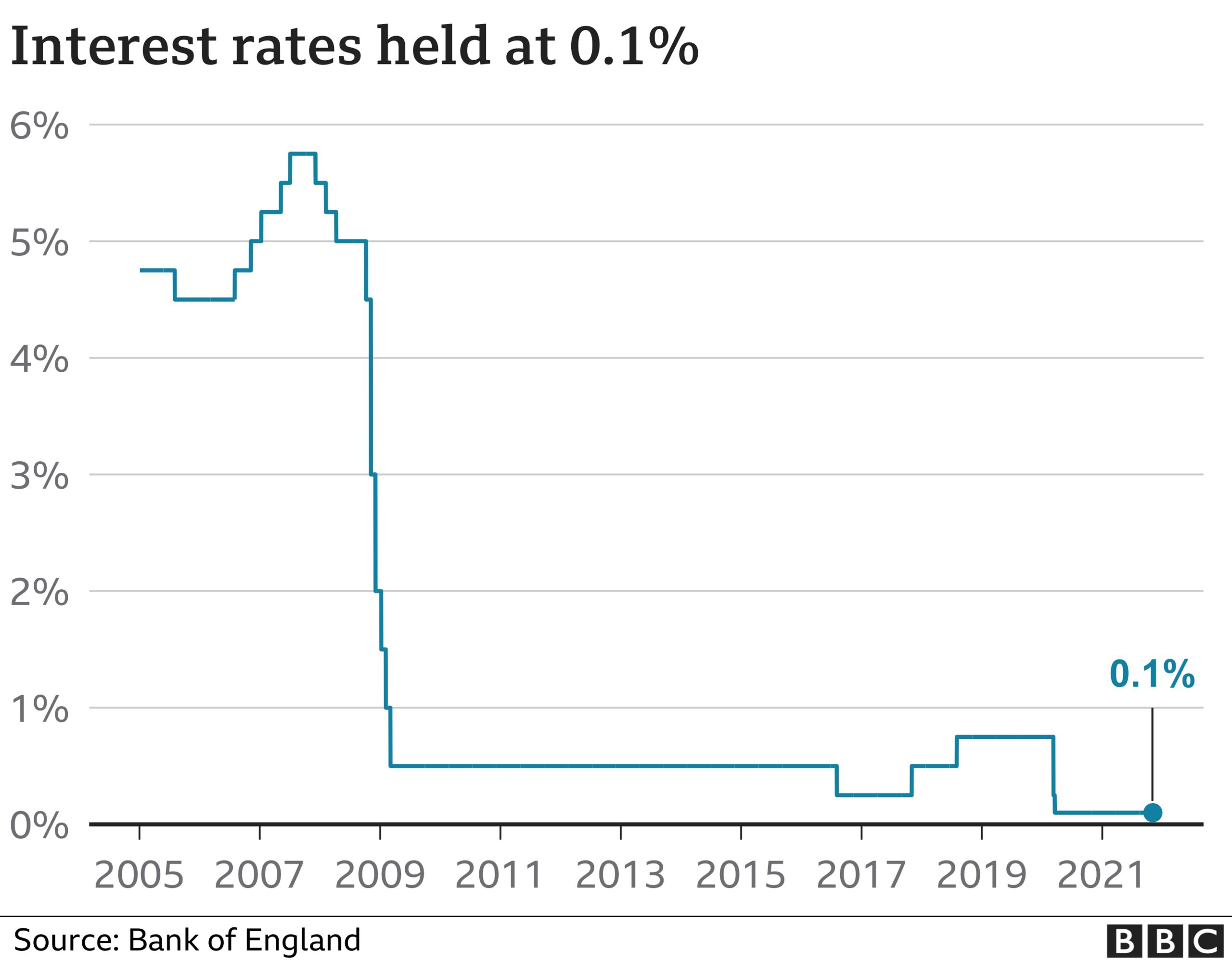

On Thursday, Bank policymakers voted 7-2 in favour of no change from the current record low rate of 0.1%.

Bank governor Andrew Bailey said the decision had been a "close call".

The Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) said there was "value" in waiting to see how the jobs market coped with the end of the furlough scheme.

However, it did not rule out a rate rise at its next meeting in December.

The MPC meets every six weeks. When pressed on when a rate rise might come, Mr Bailey said: "From now onwards."

He said the MPC had "spent many hours" pondering its decision, adding: "The calls are close, they are quite hard. It's a reflection of the position we're in."

In a BBC interview, Mr Bailey said current conditions were different because inflation was being caused by global "supply shocks" rather than demand pressure in the UK economy.

"Putting interest rates up, I'm afraid, isn't going to get us more gas," he added.

But he said that interest rates were not going to return to levels seen before the 2008 financial crisis.

"For the foreseeable future, we're in a world of low interest rates," he said.

"That doesn't mean that they don't rise and fall within that sort of bound. But I want to be quite clear, we're not signalling that there's going to be some very sharp return to the world that we can just about remember before the financial crisis."

Mr Bailey said the MPC wanted to see "more evidence" of how the labour market was evolving before raising interest rates.

However, he stressed: "We think there will be some need to increase interest rates to bring inflation sustainably back to target. And we will be ready to do that."

While the MPC voted to keep interest rates on hold, policymakers were split on the decision.

Two of the nine members, Dave Ramsden and Michael Saunders, voted to raise rates immediately to 0.25%.

Rates were cut to their current level in March last year in response to the effects of the coronavirus pandemic.

But the reopening of the economy has fuelled price rises, prompting expectations that the Bank would increase borrowing costs.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey said the decision to hold the interest rate at 0.1% was a "close call"

The pound fell by nearly 1% against the dollar to $1.3556 following the Bank's decision, reflecting the fact that investors had bet on a rate rise.

Financial markets expect the interest rate to hit 1% by the end of next year.

How much further could prices rise?

Electricity and gas prices have surged as the global economy reopens.

Factories and businesses are also struggling with staff shortages and a backlog of orders, which has also pushed up prices.

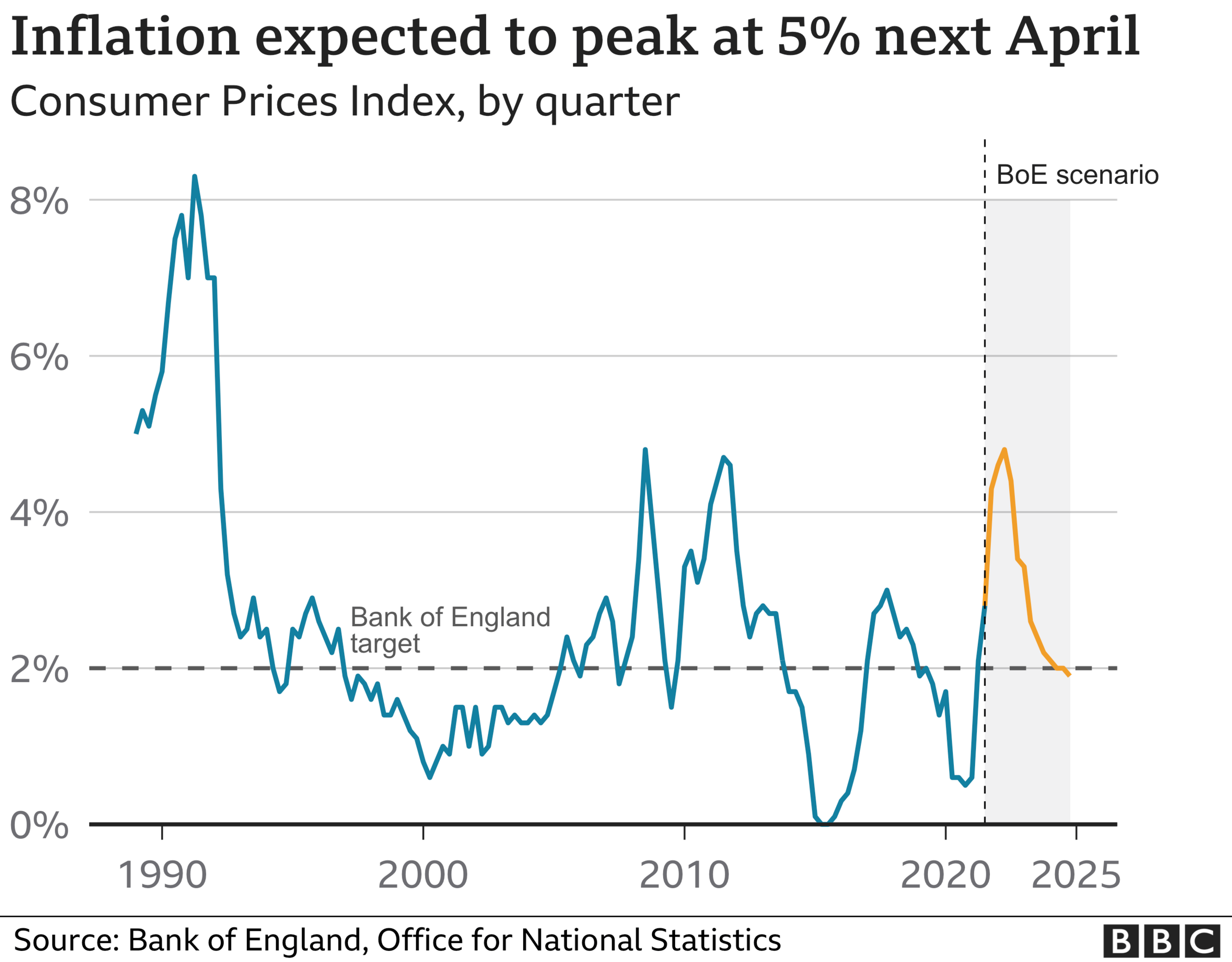

The Bank expects inflation to peak at 5% next April, up from 3.1% in September.

This would be the highest rate in more than a decade and far higher than the Bank's target of 2%.

The Bank said households faced "substantially" higher energy bills next year.

Policymakers also said food prices were likely to rise in the run-up to Christmas.

However, they added that the sharp increase in inflation was expected to be "temporary", with price rises expected to ease back towards 2% in the second half of next year.

What does this mean for households?

Higher inflation is expected to put pressure on household finances for the next two years.

The Bank's latest Monetary Policy Report expects price rises to outpace pay increases in 2022 and 2023.

So-called real incomes are expected to barely grow in 2024.

High Street banks use the interest rate set by the Bank's MPC to set their own mortgages and savings rates.

While an increase in interest rates would have been bad news for borrowers, many mortgage holders would not have faced an immediate increase in payments.

Three quarters of mortgage holders are currently on fixed-rate deals.

What about the economy?

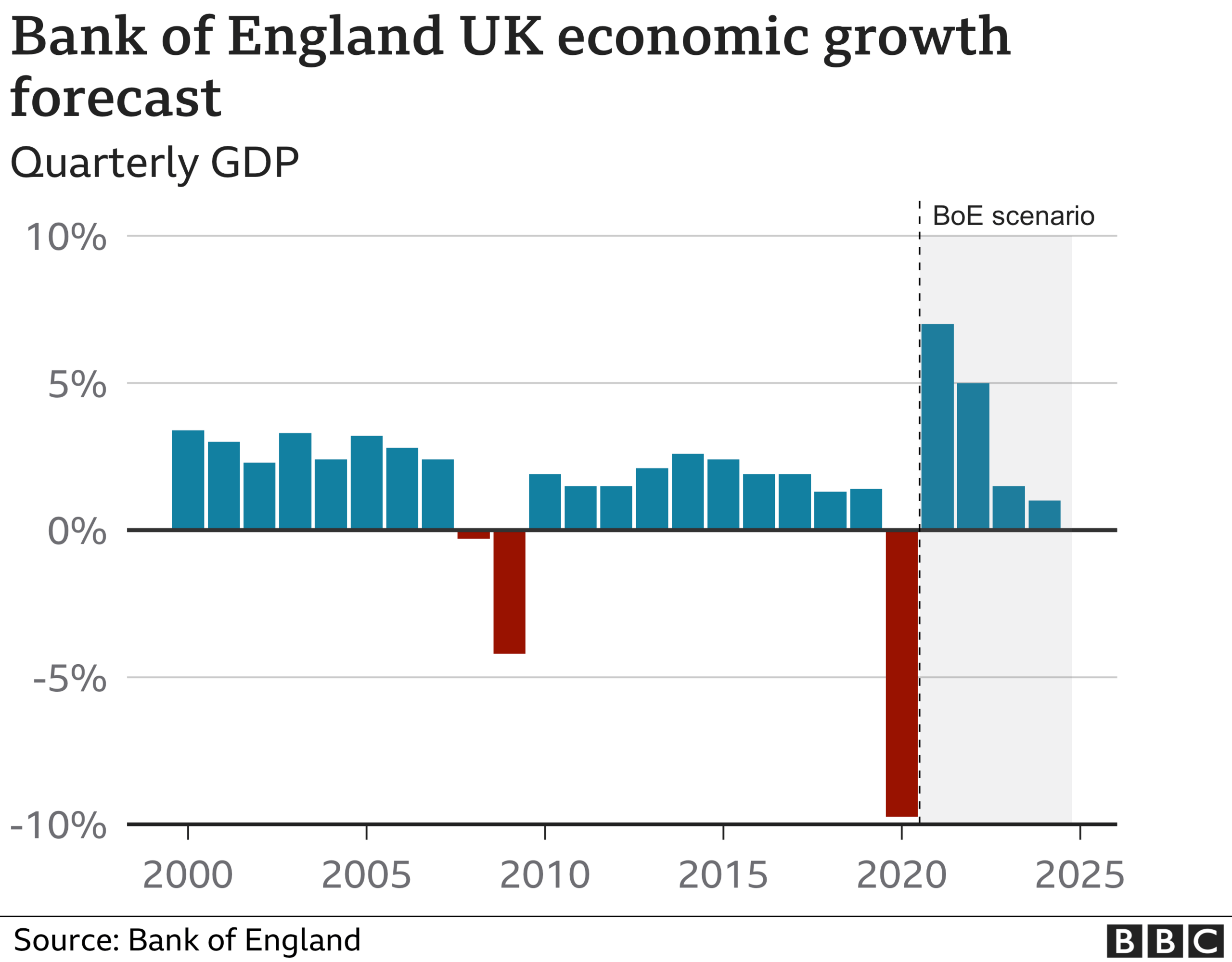

Higher prices are expected to weigh on growth in the near term.

The Bank now expects the economy to grow by 1.5% in the three months to September.

This is almost half the rate expected at its previous forecast in August.

As a result, the economy is not expected to get back to its pre-pandemic size until the start of next year. It had previously expected the economy to recover by the end of 2021.

The Bank also cut its forecast for annual growth in 2021 and 2022 to 7% and 5% respectively, down from 7.25% and 6% previously.

In September, around a million workers were still on the government's furlough scheme that subsidised wages.

The scheme ended in October and the Bank expects most of those who were on furlough to return to work.

While the peak in inflation next April is expected at a time when around 40% of workers are negotiating pay deals, the Bank does not expect higher prices to lead to big demands for pay rises.

It suggested that many workers were still scarred by the financial crisis, when many accepted slow pay growth or wage freezes even amid rising inflation.

Where next for interest rates?

Be in no doubt, people and businesses should prepare for rates rising in the coming months, perhaps as high as 1% from their record lows of 0.1%, but not precisely this month.

The message from the Bank of England is that the economy has been hit by supply chain bottlenecks, both for goods and workers, pushing back the time when the economy regains all the lost pandemic growth into early next year. And while the inflation picture is now worse, with a forecast peak of 5% when the energy price cap is due to be further increased in April 2022, there is not much the Bank thinks it can do about the global drivers of this.

Where the Bank can act is around the persistence of this inflation into 2023 and 2024. They do now feel there is a risk that pressures from rising prices last. If interest rates were kept at these emergency lows, the Bank forecasts inflation would still be about 3% in late 2024.

But acting now would have required immediate evidence of a spiral in wage rises across the economy. On balance, the members of the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee want to see official data in a fortnight on the impact of the end of the furlough scheme on the jobs market.