The small nuclear power plants billed as an energy fix

- Published

Seaborg plans a range of nuclear power barges

"We'll likely have more accidents than existing reactors because it's a new technology, but these will be accidents and not disasters," says Troels Schonfeldt, co-founder of Denmark's Seaborg Technologies.

His nuclear power company is one of several developing a new generation of smaller nuclear power plants.

Like others in the industry, Mr Schonfeldt wants to address fears over safety.

In Seaborg's case their reactors will be housed on floating barges and use molten salt to moderate reactions.

Mr Schonfeldt argues that this set-up and location means large-scale disasters, perhaps caused by a terrorist attack, simply aren't possible.

"If a terrorist bombs the reactor and the salt sprays everywhere, then it solidifies and stays. You go and clean it up," he says.

"It's a very, very different scenario to bombing an existing reactor, where you'd have a gas cloud that wouldn't be contained on your own continent and would basically cause an international disaster."

Troels Schonfeldt the co-founder of Denmark's Seaborg says his reactors are disaster proof

Seaborg's modular power barges can generate between 200MW and 800MW of electricity - enough to power up to 1.6 million homes.

The makers of these smaller reactors also claim that as well as being safer, they will be much less expensive than their larger cousins.

Traditionally, building large nuclear power stations involves taking components to a huge building site and assembling the reactor there. But these new so-called modular designs can fit together like jigsaws and largely be assembled in factories, making for a much simpler construction project.

That's certainly the hope at Rolls-Royce, which has just received a £210m grant from the UK government and a £195m cash injection from a consortium of investors, to develop its own small modular reactor (SMR).

This means that 90% of a Rolls-Royce SMR power plant could be built, or assembled, in factory conditions.

"So you build, in our case, probably three factories. In these factories you create and assemble components. And these modules are then put on the back of trucks," says SMR chief engineer, Matt Blake.

"The limiting factor for the size of the reactor was - what is the largest single component that can go on the back of a truck?"

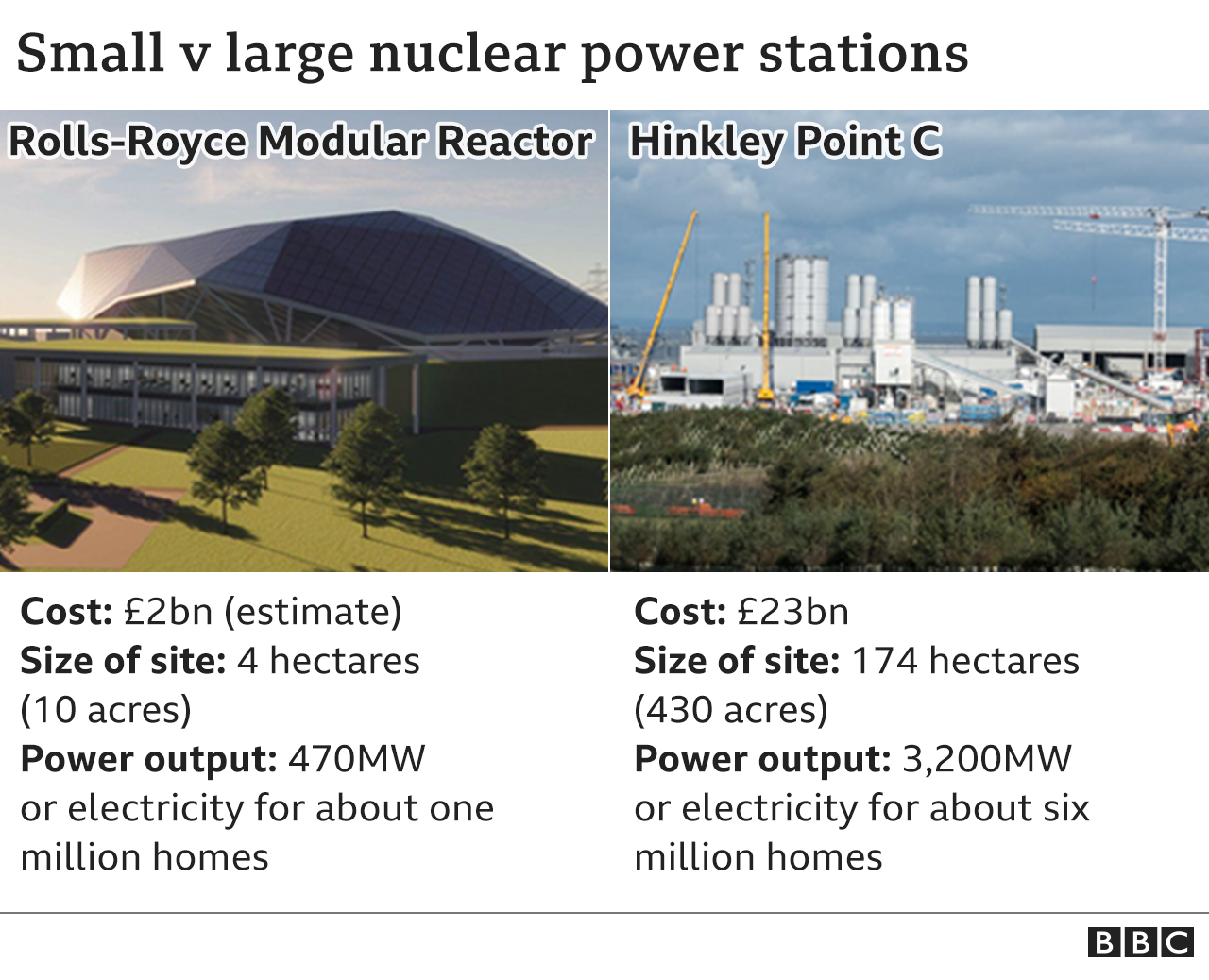

At an expected cost of around £2bn each, the Rolls Royce SMR would cost a tenth of the £23bn bill for the UK's newest nuclear power station at Hinkley Point in Somerset.

Each Rolls-Royce SMR will have a capacity of 470MW - so enough electricity to power one million homes.

As many as 16 SMRs might be built dotted around the UK, with the first planned to come online in 10 years' time: eight sites have been identified.

"We're the size of two football pitches and we're more akin to an Amazon warehouse in terms of disruption than a Hinkley Point, so that should open up a broader range of siting opportunities," says Mr Blake.

Rolls-Royce hopes their reactors will not just supply the National Grid. It thinks other customers like data centres, and firms producing hydrogen and synthetic aviation fuel, will be interested too.

It is also hoping to sell its reactors abroad, with their smaller size an advantage.

"SMRs are different in that financing will be simpler - putting together financing for £2bn is obviously a lot simpler than 10 times that," adds Mr Blake.

California's Radiant says its reactor will fit into a shipping container

Based in California, Radiant Nuclear's ambitious tagline is 'making nuclear more portable' and it wants to shrink nuclear power plants down even further.

It says it is developing a reactor the size of a shipping container, that could be easily transported by truck.

The project is still in the very early stages, with the company planning a fuelled demonstration in 2026 and units in production by 2028.

But Radiant does not see its reactors competing for market share with the big power plants that connect to the energy grid.

Instead "it's in direct competition with the diesel generators that you'd use for back-up power, or one you'd use in a remote off-grid location," says the company's chief executive Doug Bernauer.

"That's anywhere you need back-up power, such as data centres, hospitals or military bases."

Small nuclear reactors are not much better than large ones according to CND's Kate Hudson

However, anti-nuclear campaigners are not persuaded or reassured by safety claims coming from new entrants to the nuclear power market.

"SMRs will still be vulnerable to nuclear accidents and terror attacks; they risk nuclear proliferation, and can produce more nuclear waste than conventional reactors per unit of electricity," says Kate Hudson, director general of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament.

Mr Blake from Rolls-Royce says the process for dealing with nuclear waste is well established: "Spent fuel is retained at the site and will be processed in the same way as a standard PWR (pressurised water reactor), like Sizewell or any other site"

"It will be held at the site, and eventually transferred to Sellafield, or a geological disposal facility deep underground," he explains.

The proponents of small nuclear plants say their technology will be necessary to meet an expected doubling of demand for electricity in the UK from consumers by 2050.

But Ms Hudson is still sceptical: "It is an unproven and untested technology that will still cost the taxpayer unspecified, and likely large, amounts of money."

"Even with the most ambitious timescale," she adds. "We will have to wait 10 years for an SMR to produce energy, when renewable alternatives and energy efficiency programmes are available now."