Workers call the shots as job vacancies boom

- Published

- comments

Job vacancies hit a fresh record high in October as employers continued to struggle with worker shortages, official figures show.

The redundancy rate was also largely unchanged despite the end of the furlough scheme in September, making it even harder to fill empty posts.

Employers report having to improve pay and benefits to attract new recruits.

Yet one analyst warned the trend was likely to continue amid a shortage of younger workers and those over 50.

According to the Office for National Statistics, external (ONS), there were 1.17 million job openings in October - almost 400,000 higher than before the pandemic.

Moreover, some 2.2 million people started a new job between July and September, it said.

'I can't get the staff'

Daniel Browne, who runs Blossom & Browne's Sycamore, a laundry service for London hotels, says trying to hire new staff has been "horrific" this year. He says Covid and Brexit have reduced his headcount from 140 to about 80, making it impossible to meet client needs.

He has had to put up wages amid a "price war" for temporary staff, and improve pay and conditions for existing staff in order to retain them.

"We're trying to create a happier workforce," he told the BBC. "We're starting at 8am, rather than 7am because that was the staff feedback we had. We're trying to raise our wage rates as much as we can and pass that cost onto our clients."

Furlough impact

Some had thought a rise in redundancies after the furlough scheme ended would make it easier to fill the high number of vacancies. An estimated 1.1 million people were still on the job support scheme in its final days.

Yet while redundancies rose slightly in the three months to September, the unemployment rate fell to 4.3%, close to its pre-pandemic level.

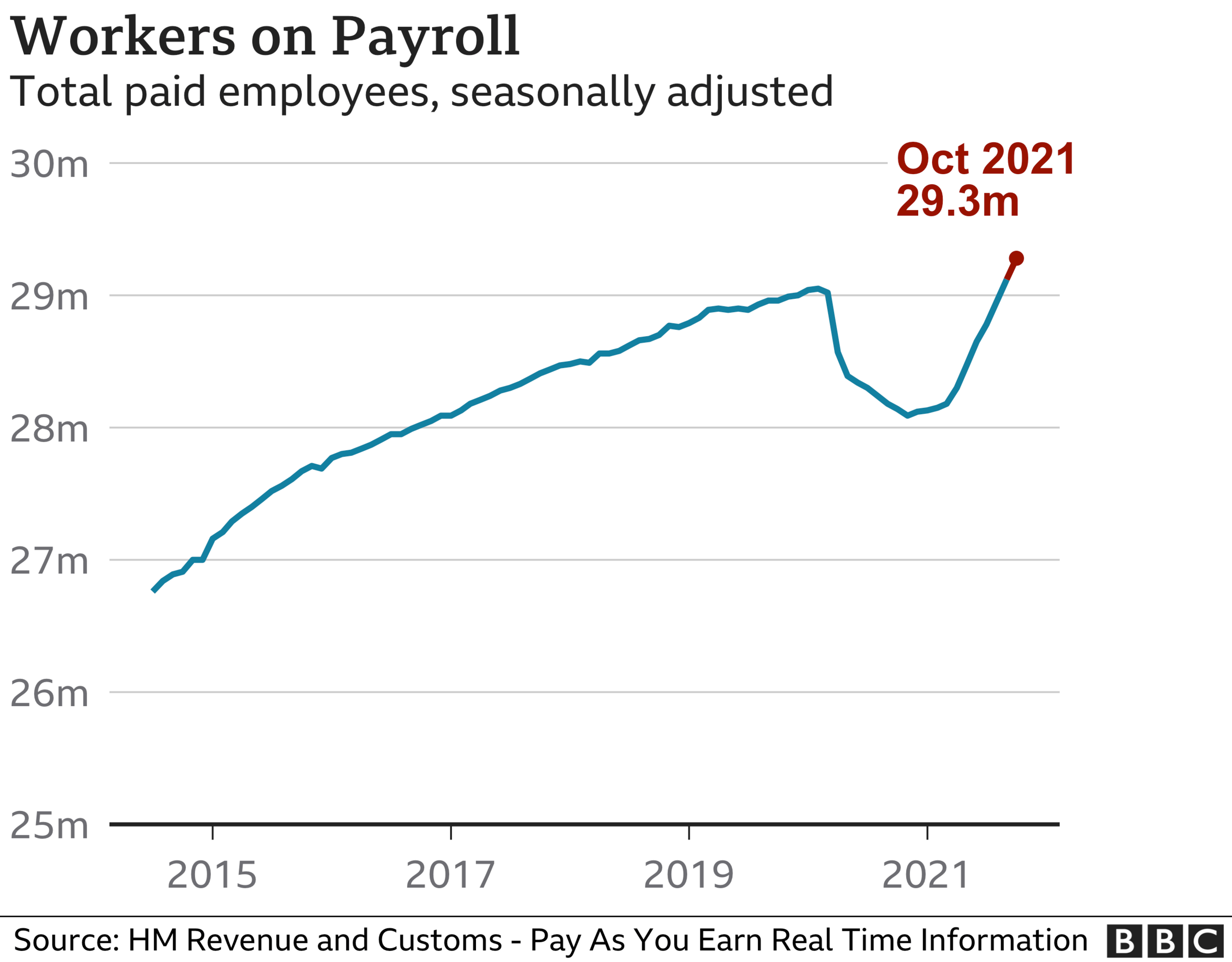

Moreover, there were 160,000 more workers on payrolls in October than September.

"It might take a few months to see the full impact of furlough coming to an end, as people who lost their jobs at the end of September could still be receiving redundancy pay," said Sam Beckett, head of economic statistics at the ONS.

"However, October's early estimate shows the number of people on the payroll rose strongly on the month and stands well above its pre-pandemic level.

"There is also no sign of an upturn in redundancies and businesses tell us that only a very small proportion of their previously furloughed staff have been laid off."

'People just aren't turning up'

Angela Burns is another employer struggling to recruit in the current climate. She runs a group of four hotels across the Midlands and Gloucestershire, and has at least 20 vacancies, with chefs and housekeeping staff among the most difficult positions to fill.

"There's a huge demand out there for people to come to our hotels. The phones have been so busy, but we're having to close areas of the hotel because we don't have the staff to cope," she told the BBC.

Angela said the recruitment process had been frustrating, and that many candidates "just don't turn up for interview". She added that people were looking for more than a just pay rise these days.

"It's about flexible working, it's fitting things in with their family, it's training, it's future career prospects as well," she said.

'Participation gap'

Gerwyn Davies, an analyst for the Chartered Institute of Professional Development, said employees were "taking advantage of the tight 'job-seeker friendly' labour market [and] re-thinking their career priorities after the pandemic".

In response, he said employers needed to improve how they developed and retained staff, going "beyond simply a competitive salary".

"[It could] include the quality of line management, the availability of different types of flexible working arrangements and opportunities to develop new skills and progress," he said.

The Institute for Employment Studies (IES), a think tank, said there was a huge "participation gap" in the labour force caused by older people not going back to work after losing their jobs, and more young people staying in education.

It added that it expects the trend to continue.

"All told, we've nearly a million workers now missing from the labour market, and their absence is now holding back our recovery and adding to inflation," said IES director Tony Wilson.

"We're still doing nowhere near enough to help get people back into work, particularly for older workers, disabled people and parents."

Could interest rates rise?

October's strong jobs data appears to increase the likelihood that the Bank of England will raise interest rates from their record lows before the end of the year, as it seeks to tame inflation.

The cost of living has increased sharply since the economy has reopened and is expected to hit as much as 5%, according to the Bank's forecasts.

Many analysts had expected the Bank to raise rates at its meeting earlier this month, but it chose to keep them on hold. On Monday, Bank governor Andrew Bailey told MPs it had been waiting for official data on the impact of the end of furlough before it made a move.

Paul Dales, chief UK economist at Capital Economics, said: "If the next labour market release on 14 December tells a similar story, we think that will be enough to prompt the Bank to raise interest rates from 0.10% to 0.25% at the meeting on 16 December."

But others noted that the Bank may wait given that the UK's economic recovery slowed between July and September due to global supply chain problems.

"Uncertainty is not over yet," said Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG UK. "We expect the Bank will wait with the first hike until February next year, but... an earlier move in December cannot be ruled out."

The Bank of England said last week that one of the reasons it didn't want to raise interest rates yet was because of the uncertainties in the labour market, not least because at the end of September there were still 1.1 million people on furlough.

The fear has always been that that would translate into a big jump in unemployment. Today's figures provide some measure of reassurance about that, showing the number of payrolled employees rose sharply in October.

The Bank is also keeping a close eye on upward pressures on inflation. While average earnings have been growing much faster than inflation, they've more recently slowed down, rising by 4.9% excluding bonuses on the latest figures.

That's still faster than inflation but when you strip out distortions relating to the pandemic, the Office for National Statistics reckons it's closer to 3.4%.

Given the official forecasts that inflation will get up above 4% next year and possibly as high as 5%, the big risk now looks to be less that pay growth might drive inflation up - and more that pay doesn't keep up with prices, dragging living standards down.

- Published11 November 2021

- Published5 November 2021

- Published16 November 2021