'If you eat here, you're dining with rats'

- Published

Add a plague of rats to all the other challenges New York City has faced in 2021

Diem Boyd was sitting outside a restaurant in New York's fashionable Greenwich Village in September, when a family of rats scurried across her feet.

"Within seconds everybody jumped up," she says."We lost our appetite."

Everyone in New York has a similar story to tell, she explains. "We have a complete and utter rat explosion."

"You see them when you come out at night," agrees Deborah Gonzalez, who, like Diem, lives in Manhattan's Lower East Side. "When you walk on this block you see them running back and forth."

It is difficult to gauge precise numbers, but calls to New York City's complaints hotline mentioning rodents have jumped this year, 15% up on pre-pandemic levels.

"Obviously New York has always had rats," says Marcell Rocha, who also lives in the neighbourhood, but now "they are bigger and bolder, they jump at you. They're gymnastic, doing backflips".

Diem, Marcell and Deborah object to the way restaurants have taken over the streets in their local area

So, what's changed?

Diem, Deborah and Marcell put the blame for this new plague, squarely at the door of the al fresco dining that has spread through the city during the pandemic, encouraging many more people to eat at outdoor tables.

Hundreds of New York's streets are now lined - often on both sides - with ad hoc shelters, completely altering the urban landscape. To give you an idea of the scale - there are more than 11,000 new outdoor eating spots.

Some of these new venues are little more than a frame and a scattering of chairs, others are sturdy structures with floors, fairy-lights, flower pots and electric heaters.

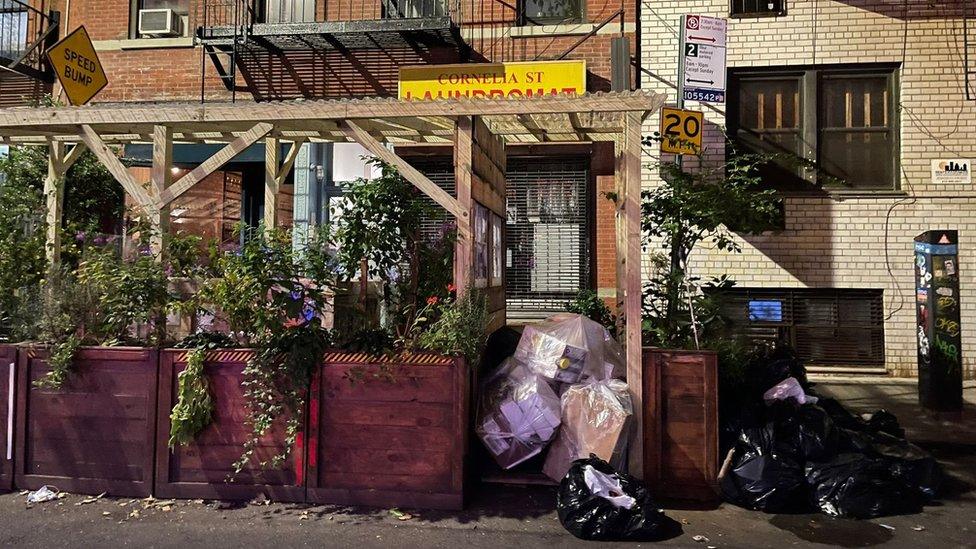

Hundreds of New York's streets are now lined with ad hoc shelters

Diem, Deborah and Marcell say the shelters encourage "mile high" piles of black plastic rubbish bags to accumulate at the roadside, and provide the perfect hideout for rats under the floorboards.

Nevertheless, these venues have proved hugely popular with customers over the last year and a half. Too popular in fact, for local residents.

"This is hell on earth because of the crowd and the noise," says Marcell. The Lower East Side has always been a lively neighbourhood, but last summer it felt like "living at a festival" he explains.

At the start of the pandemic, New York's mayor Bill de Blasio launched an "open restaurants" scheme. It was part of a wider vision of a city less dominated by traffic and more focused around its residents and visitors. But, above all, it provided a lifeline to the hospitality industry.

Residents are concerned the outdoor dining craze is creating access issues and increasing littering

And while the initial permission to set up outdoor eating areas was a temporary emergency measure in the teeth of the pandemic, in late 2020, as indoor dining began to resume, the mayor announced he wanted to make widespread outdoor dining a permanent feature.

"Open Restaurants was a big, bold experiment in supporting a vital industry and reimagining our public space - and it worked," Bill de Blasio said.

"As we begin a long-term recovery, we're proud to extend and expand this effort to keep New York City the most vibrant city in the world."

The City Council - the elected body that manages New York affairs - is now in the process of debating and voting on removing zoning regulations that limit outdoor dining.

That move has angered Diem, Marcell and Deborah. They say no proper assessment has been made of the impact the restaurant sheds are having. And they, along with more than a dozen other residents, have launched legal action to try force the city to look more closely at the effect a permanent expansion of outdoor eating and socialising will have.

"That was not the plan," says Deborah. She adds, when the emergency scheme was launched, residents supported it, wanting to support the struggling hospitality sector. But now they feel their views are being ignored.

Some residents are calling for a review of the impact of outdoor dining

She says the rats, the crowds, the vomit and the dirt, are upsetting, but she also worries for elderly residents trying to navigate busy pavements.

Fire engines have to slow to a crawl to pass through streets with restaurant sheds, she says. Others have raised similar concerns, and in May the New York City Fire Department tweeted, external that the sheds had delayed them arriving to the scene of a fire at a Chinese restaurant in central Manhattan.

Residents from Chinatown to Queens, Brooklyn to Greenwich Village, are now calling for a review of the impact of outdoor dining.

Some say it is fundamentally altering the character of neighbourhoods that weren't previously dominated by noisy nightlife, in other areas it is exacerbating existing problems.

As the weather has got colder, the sheds have been enclosed in sheets of plastic, defeating the original health and safety purpose of providing a well-ventilated dining space. Graffiti has started to appear on the outsides of sheds, some of which are no longer being used and falling into disrepair.

"It's like a shanty town," says Diem.

But not everyone sees it that way.

Jacob Siwak, head chef and owner of Italian restaurant, Forsythia, just across the road from where Deborah lives, finds the criticism of the outdoor dining scheme infuriating.

"It's just insane to me that people are focusing on these minutiae, that might be a slight negative, when there are so many radical positives," he says.

Jacob, head chef and owner of Forsythia, says the scheme offers huge advantages

Mr Siwak says he's sure his restaurant has added to the value of the whole block. "And it allows me to employ more people. I have a lot of people on staff [that] I'm able to pay a New York living city wage."

There are rules about how far out into the road he's allowed to put the shed, he points out, the equivalent of the width of a parked car. So, he believes concerns about emergency vehicles getting through are "invalid".

He admits New York has a problem with its refuse collection, but says dining sheds are not to blame. And his restaurant is not making it worse. "We use ceramic plates, linen napkins, silverware. We're not accumulating garbage," he says.

Andrew Rigie, executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance says making the outdoor dining scheme permanent could prove just the catalyst the city needs to tackle its long-standing refuse problem.

New Yorkers' rubbish is mostly left on the roadside in black plastic bags to be collected by public or private collectors - depending on whether it is domestic or commercial waste - a system that has been disrupted by the pandemic and the sheds.

Mr Rigie agrees the system needs improvement, but says that shouldn't stand in the way of outdoor dining.

"The reality now is that restaurants and the dining public have got a taste for outdoor dining and they love it. There's demand to make it permanent."

But the current temporary programme - set up at the height of the crisis - isn't being made permanent. Instead, a new set of standards and regulations is being hammered out to address many of the residents' concerns, including sanitation practices; noise at night; and what activities are permitted, he says.

Restaurant and bar owners say the sheds have allowed them to keep more people in work during the pandemic

"Are people going to have different opinions whether or not they want different types of activity on the street? Of course. New York City is a big complex place with many competing uses for the public space," he says.

The City says the new programme's key principles will be accessibility, appearance - including cleanliness, equity - allowing all neighbourhoods to take part, ensuring restaurant set-ups work in their neighbourhood context and safety, including access for emergency vehicles.

The Department of Transport, which will oversee the permanent programme, and the Department of Planning launched a consultation, external asking New Yorkers how they think those aims can best be achieved.

"The incredible success of outdoor dining shows how we can reimagine our streetscape to better serve our neighbourhoods," says department of transport commissioner, Hank Gutman.

Mr Gutman says he will consult with the public to "craft guidelines" that will increase accessibility, safety and address concerns such as noise, hours of operation and sanitation.

But many residents remain deeply sceptical. They say the consultation won't reach many parts of the community, especially those that aren't active online. They argue the scheme has been poorly policed and worry the same will be true for a permanent one.

Even if stricter conditions are agreed and enforced they're suspicious of the forces at play behind the scheme.

"This is no longer about recovery," says Diem. "Doubling restaurants' capacity by allowing them free use of the street, means landlords are being gifted one of the biggest public landgrabs in New York City's history."

They can push up rents, and will favour bars and restaurants over other small businesses as a result, she argues, further undermining the character of many neighbourhoods.

"Ultimately our argument is this, aside from it being a public safety health hazard, on every level," says Diem. "This is for developers and landlords to benefit at the expense of everyday New Yorkers."