The woman working to get unwanted food to the hungry

- Published

Maria Rose Belding started the Means Database as a teenager

"It was one of the most brutal feelings I've ever had," says Maria Rose Belding.

Maria Rose is talking about the moment that changed her life and kick-started a food venture now helping to curb food waste across the United States, that's inspired other people around the world.

She was just 14 and volunteering at a local charity which gave food to hungry families in her home city of Pella in Iowa.

"I was the youngest person there," she explains.

Volunteers distributing donated food in Philadelphia

"I would go outside and throw things [food items] away that had expired, while there were people sitting in the parking lot, waiting to come get food. And they could see me throwing away food in front of them."

This sparked an idea. Working with friends and colleagues, they came up with the Means Database - a website to connect food businesses, like restaurants and caterers, with charities and non-profit organisations that distributed food to hungry people.

When a restaurant had food that might go to waste it could quickly log this on the Means Database and the nearest non-profit that could use it would step in and claim it.

The restaurant would not have to pay waste or dumpster charges, the food would not go to waste and someone was fed.

The idea took off almost immediately.

Database partner, Pablo Rodriguez-Masjoan from EP Kitchen in Rhode Island fills a community fridge with food

"We started in two states [but] by the end of 2015 we had them in 26 [states]. We ran it out of my dorm. By the end of our first year, I believe we moved 25-30,000lb (11-13,000kg) of food," says Maria Rose, who is now chair of the Means Database board.

In 2021 alone, the database doubled the amount of food it rescued each month.

It works with big corporations such as Starbucks coffee shops, as well as sole traders. In the state of Florida it works with 160 businesses.

The database now operates across 48 states in the United States, as well as Canada and there has been interest in Europe.

It is hoped that successfully tackling food waste could represent a big step forwards in ending food poverty and hunger - in 2018 the Boston Consulting Group estimated that one third of the food produced in the world gets thrown away.

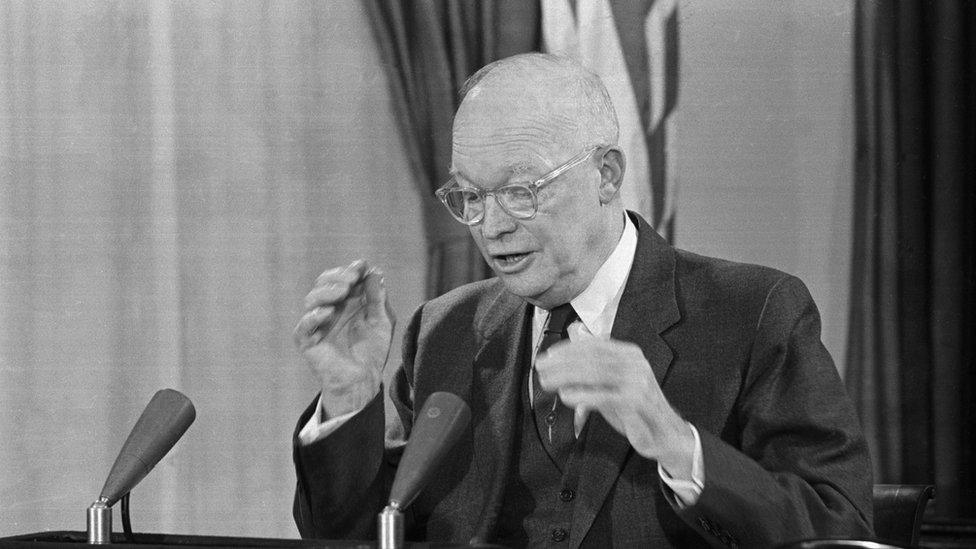

US President Eisenhower launched the World Food Programme in 1961

Maria Rose is one in a long line of people working hard to eradicate world hunger. Back in 1961, US President Dwight Eisenhower initiated the World Food Programme - the founding idea was to bring food from countries with excess supplies and redistribute it to those in need.

Nearly 60 years later, the World Food Programme (WFP), part of the United Nations, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize.

"When we hear about a crisis, it's like that same drive that an individual feels, but on steroids," explains Valerie Guarnieri, the assistant executive director of the WFP.

The World Food Programme does more than distribute food in places affected by war and famine, it also works to improve access to food in areas where there is no conflict.

Peter Mumo created a cold water pumping system to help farmers irrigate their fields

Ms Guarnieri says the WFP helps support more than 40 nations around the world with school meals, pointing to evidence that by providing a nutritious meal "you can bring children to school," she explains.

One of the students who has directly benefited from this scheme is Peter Mumo, who remembers the day the trucks arrived at his school in rural Kenya.

"My performance was dropping, but after the school meals I became a top student in my class," he says. "I maintained that for the rest of my schooling life because I never missed school. I was attentive in class because I really wanted to get this education and go all the way to university."

Mr Mumo eventually studied engineering at university and afterwards went on to work for a pesticide company in Nairobi. He started putting some of his salary away each month for an idea he had had for helping the community where he grew up.

His idea for a cold water pumping system to help farmers irrigate their fields was so promising he was awarded a Mandela Washington Fellowship which gave him the opportunity to pitch to potential investors.

Today his irrigation system is used by more than 400 farmers in the area he grew up and he has started another project to help those farmers store their food in communal fridges.

A Kenyan farmer using Peter Mumo's irrigation system

Maria Rose, Valerie and Peter spoke to the BBC for a programme on the BBC World Service called Generation Change about young people tackling big global issues. and the Nobel Laureates whose footsteps they are following in.

"We know what it takes to solve the problem of food insecurity," says Ms Guarnieri from WFP.

"It takes ensuring that all people have access to food, and part of that is about growing more food and growing it in a sustainable way. And part of it is about addressing the other barriers in the supply chain that stop all people from having access to nutritious food at all times.

"We don't need new inventions, or new techniques to do it. We need policy change, we need financing and we need commitment to action. I think young people can really help drive that through."

Maria Rose Belding is also realistic about the possibility of solving hunger. "Solve is an interesting term," she says.

"If you want to solve hunger, you have to solve poverty, you have to solve substance use disorders, you have to solve educational failure, you have to solve armed conflict, you have to solve domestic violence - just to name five.

"I don't know that we will ever truly solve hunger. But we can make it an aberration. Instead of a rule."

Generation Change is a co-production by the BBC and Nobel Prize Outreach

Listen to Generation Change on The Documentary, BBC World Service.

- Published5 January 2022