How delivery apps created 'the Netflix of food ordering'

- Published

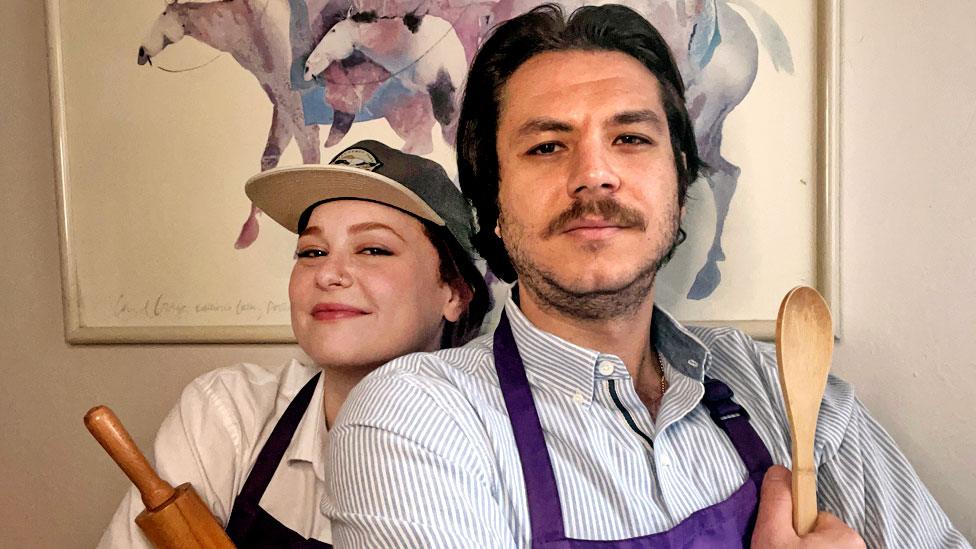

Emre Uzundag and Yonca Cubuk run a professional takeaway business from their home kitchen

Husband and wife, Emre Uzundag and Yonca Cubuk, say they are now "living their small dream", all thanks to a food delivery app.

The Turkish couple moved to New York in 2020, and due to coronavirus they found themselves stuck in their small apartment in Brooklyn.

Homesick, they started to cook more and more Turkish food, to help them cope with the stresses of lockdown. "Which was a mental necessity during the pandemic," says Ms Cubuk.

They then moved on to cooking meals for friends around the city, and Ms Cubuk says the feedback was incredibly positive.

"They started to tell us that we should turn it into a career."

Despite neither of the pair having worked as a professional chef before, last year they decided to take the plunge, and signed their business up to a new food delivery app called Woodspoon.

While the huge market-leading delivery apps, such as Just Eat, Deliveroo, Uber Eats and DoorDash (the biggest in the US) now list many large restaurant chains, Woodspoon's business model is entirely different.

It was launched at the start of 2020 to link home cooks - people literally cooking from the kitchen in their house or apartment - to customers who want a fresh, homemade takeaway, rather than something from a chain restaurant.

BanBan Anatolian Home Cooking also offers dishes of Armenian, Persian, Arab and Jewish influence

You order via the Woodspoon app, which sends the details to the relevant home chef. Then, when the food has been cooked, it is picked up and delivered by a Woodspoon driver.

Currently available across New York City and into New Jersey, with more than 120 cooks currently on its books, it will soon expand to Philadelphia.

Emre Uzundag and Yonca Cubuk's BanBan Anatolian Home Cooking is now available via the app four days a week, while on the other three days they work on new recipes. Ms Cubik says that they are so busy that they recently had to work on their fourth wedding anniversary.

Yet, thanks to Woodspoon, they don't have to go to the expense of renting a commercial premise.

"Woodspoon gives us a platform and a voice to tell our story," she adds. "And we are more than just kebabs and pilaf [a rice dish]... our best-selling dishes are the lentil soup and the orange spinach stew, both are vegetarian, the latter one is vegan."

New Tech Economy is a series exploring how technological innovation is set to shape the new emerging economic landscape.

Woodspoon's co-founder, Lee Reschef, says that launching at the same time as the start of the pandemic actually proved to be helpful. "We were fortunate enough to help a lot of restaurant workers that needed to find a new line of income," she says.

Before home chefs are accepted by Woodspoon they have to show proof of food safety training, and the company sends someone out to carry out an inspection of their kitchen.

The chefs also have to register their business with the relevant local authority, and be subjected to official food hygiene tests.

While Woodspoon is currently focused on US expansion the concept could also work in the UK, where it is also legal to run a food business from a residential property., external

With the pandemic closing restaurants for long periods of time, the past two years has been boom time for takeaway delivery apps. The UK's largest, Just Eat, saw its revenues hit £725m in 2020, up 42% from 2019, , externalwhile those at DoorDash jumped more than threefold to $2.9bn (£2.1bn).

Yet, while many of us are increasingly using these types of apps, people often cite one frustration - that you cannot order from multiple restaurants at the same time, and get all the different dishes delivered together.

That is, however, now changing, with a small but growing number of apps starting to offer that service.

One of those at the forefront is US app, Go By Citizens, which is run by restaurant and takeaway group C3. It allows its customers to order from a number of its brands at the same time, such as Umami Burger, Krispy Rice, Cicci di Carne, and Sam's Crispy Chicken.

To ensure that the food is all cooked and ready for delivery at the same time, C3 says it operates 800 so-called "dark" or "ghost" kitchens across the US - warehouse cooking facilities that house a number of kitchens under the same roof, all making delivery-only meals.

C3 now runs 800 ghost kitchens across the US

"Our app allows consumers to pick, choose and group their favourite menu items [together] from an array of C3 brands in a single order," says C3 chief executive Sam Nazarian. He describes it as "the Netflix of food ordering".

In addition to C3 brands, the company is inviting other people's restaurants and food businesses into its ghost kitchens and tech platform, including California's Soom Soom Fresh Mediterranean and Florida's Cindy Lou's Cookies.

C3's Go by Citizen app allows customers to order from a number of its brands, including Sam's Crispy Chicken

Meanwhile, US ghost kitchen business, Kitchen United, also now lets its customers order from a number of different restaurant brands at the same time, via its app Kitchen United Mix.

"Everything is delivered, or available for pick-up, at the same time and on the same bill," says Kitchen United, chief executive, Michael Montagano. "So, if someone in the household wants sushi, but another wants pizza, that's entirely doable."

Kitchen United Mix is available in 10 US locations, with another eight currently in development.

In the UK, Deliveroo also runs a number of dark kitchens, called Deliveroo Editions - where takeaway businesses are invited to set up shop rent free. However, a Deliveroo spokeswoman confirmed that, currently, the food from each offering still has to be ordered separately via its app.

Kitchen United currently offers its Mix service in 10 US locations

Whether it's a focus on home cooks, or allowing customers to order from more than one restaurant at once, does the continuing growth of delivery apps put more pressure on physical restaurants and takeaways already struggling to stay afloat?

UK food and restaurant critic, Andy Hayler, says he thinks some people might find it off-putting that an app allows you to order food from two or more restaurants at once.

"If I saw a menu offering two to three different things, this would suggest to me this is just some generic catering company, which is banging out industrial foods," he says.

There are always times when members of a household are in disagreement over what takeaway to order

Mr Hayler adds that certain foods, such as curry are well suited for delivery. While others, such as French and Japanese cuisine, struggle in takeaway form because the dishes are supposed to be well presented on a restaurant plate, and not bashed about in transit in a plastic container.

"Half of the experience [of French and Japanese restaurants] is looking at the food there," he says.